That Sinking Feeling In Your Stomach? That’s ‘Political Grief’

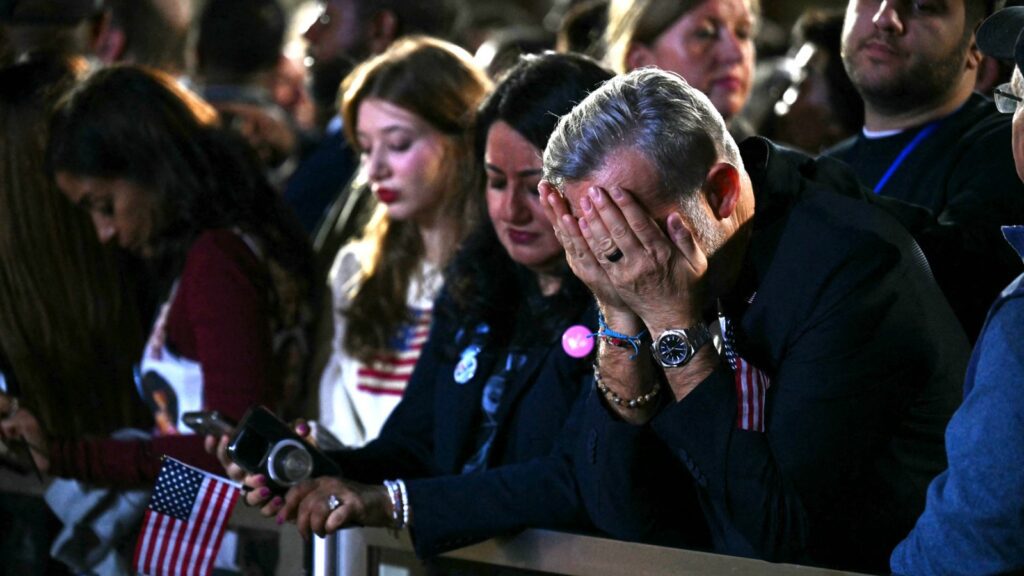

In some ways, the past few days have felt like déjà vu — processing Donald Trump’s election win like it was 2016. But in other ways, it feels very different the second time around. This time, we know what a Trump presidency could look like, and the extensive erosion of human rights, bodily autonomy, and democracy that it might yield. We’re feeling a lot of emotions all at once, though it may be hard to pinpoint what, exactly, is causing us the most distress and how we can fix it. To help us parse through the deluge of negativity, Rolling Stone tapped three mental health professionals to walk us through identifying what we’re experiencing, and how we can move forward despite facing a terrifying and uncertain future.

Keep in mind that if you’re mourning the outcome of the election, you’re not alone. It can be helpful to identify and acknowledge the ongoing collective grief a large part of the country is experiencing, says Raquel Martin, PhD, a clinical psychologist specializing in community-related and liberation psychology.

“We experience traumatic events together, and this [election] result definitely brought fears and hurt and memories of what was previously, and concerns about it only being worse,” Martin tells Rolling Stone. “Collective grief is understandable when you feel as though you put your all into something and you see an outcome that is incredibly scary for you.”

In fact, there’s an even more specific term for what we’re going through.

“Political grief is a very real thing,” says Melissa Flint, PsyD, a professor of clinical psychology at Midwestern University Glendale, noting that it occurs on both individual and collective bases. “When one struggles with a particular ideology held by those in political power, there is grief.”

This type of grief also reflects the feeling that your worldview or political beliefs — what we think is right vs. wrong, or morally valid — is under attack, she explains. In addition to the election loss, you may be mourning potential losses of your own rights and economic stability, as well as worried about the impact it might have on reproductive rights and public health. Political grief may also involve the fracturing of relationships as a result of ideological disagreements, or grappling with your identity if your values are at odds with the rest of your community.

You may also be mourning your future safety. “At the heart of political grief is a sense of despair due to the loss of predictability and safety in governmental structures,” writes Darcy Harris, PhD, a professor at King’s University College in Ontario specializing in non-death loss and grief, in her seminal article on political grief.

According to Harris, there’s also “a sense of paralysis” that occurs when you question whether those in power are capable of making decisions for the good of the country during a time of such political polarization. For those experiencing political grief, “loss of an election is equated with loss of identity, loss of agency, and loss of voice,” she writes. Its impact can be personal and painful.

What about the feelings of disappointment associated with the fact that more than half of the voting public chose a candidate who is a convicted felon, was accused of inciting an insurrection, and routinely makes inflammatory and inaccurate remarks about women and marginalized populations? “We must acknowledge this as grief,” says Dion Metzger, MD, a psychiatrist practicing in Atlanta. “It’s not only the loss of the candidate you voted for, but also the dread of what’s to come. Grief and fear are two very strong emotions to have at once.”

There’s also a component of sadness. “A lot of people are confused by the heaviness that they’re feeling,” Metzger says. “I remind them that these feelings of hopelessness, low energy and sleep disruptions can all fall under the umbrella of sadness.”

Trying to process the election results and the range of emotions that accompany it, but aren’t sure where to start? Here are some tips and strategies from mental health professionals to help you function.

It’s OK to feel shitty

Don’t put a time limit on allowing yourself to sit with your emotions, Metzger says. “If you are still feeling this way a week or even a month from now, this is OK,” she explains. “There is no timeline on grief.”

Crying can contribute to relief in some way and activate the parasympathetic nervous system. “Everyone talks about ‘fight or flight’ — that’s the sympathetic nervous system,” Martin explains. “The other system is ‘rest and digest,’ and that’s the parasympathetic nervous system, which signals your body that it’s time to slow your heart rate and reduce blood pressure, and also can help to promote a state of calm.”

Try progressive muscle relaxation

Have you spent the last few weeks (or months) with your jaw clenched, your shoulders pushed up to your ears, and your fists in tight balls? Now’s a good time to let it go.

“A lot of times we don’t realize how much tension we’re holding in our body,” Martin says. She recommends an exercise called “progressive muscle relaxation,” during which “you tense and release that tension in different parts of your body to signal your body that it’s time to relax,” she explains. It’s something you can do anywhere on your own in five minutes. Or, if you’d prefer having some guidance, Martin has a video walking you through the exercise.

Take the time you need to mourn the future we lost on Nov. 5, but as we gear up for what is almost certainly another dark chapter in American history, it’s important to recognize that we still have agency. Experiencing grief and disappointment doesn’t make you powerless, Martin stresses.

“Community is really essential in these moments, and there’s so much power in mobilizing,” she says. “When people are feeling powerlessness and hopelessness, I encourage them to find ways to take that power back, to be an agent of change in your community and your home in the world.” This could mean volunteering at a food bank, supporting local and small businesses, getting involved with your local school board, or providing essentials for unhoused populations, Martin says.

Another tangible way to get involved would be to host a skill sharing workshop. “There are so many tools and so much knowledge that would be easier for us to break down for others rather than them having others search many different resources because we are trained in them,” Martin explains. “Leading workshops like gardening, financial literacy, even car maintenance like oil changes and changing a spare will promote knowledge and autonomy.”

Martin also suggests attending any town halls in your community so you can be aware of issues that arise and can figure out how to assist. “Town halls are a great place to get to know your neighbors, but also discuss concerns and share resources,” she says. “They are also a good place to start mutual aid networks that can help support community members in time of need.”

Working in your community creates what Martin refers to as “ripples,” or positive effects that impact others and how they engage with the world. “If we’re in a community space, we operate in a system, and whatever impacts you is going to impact those around you,” she says.

Unplug as much as possible

Election coverage has been inescapable for the past several months, but now that the race is over and we know the outcome, Metzger’s prescription is to get offline. “I am advising my patients to take a break from social media, television [news], and group chats while they process,” she says. “These platforms can only intensify these scary emotions following an election.” Instead, she recommends focusing on comfort and self-care for the next week. “That could mean watching favorite shows, spending time with friends — not talking about politics — or simply getting outside for a walk,” Metzger says.

Set boundaries with others and your time

Surviving the post-election period — and the next four years — may require establishing boundaries with other people. “If something [someone says] feels off to you, acknowledge it if you feel safe enough to address it with that person,” Martin says. “But if not, use your feet. Don’t engage with them, because it is about self-preservation. It’s in your control not to spend time with them or engage with them in a certain way.”

This is especially important for people of color and other members of marginalized populations. “The number of racist and discriminatory incidents increased under Trump [last time], and it’s only going to happen again,” Martin says. “It’s only going to be worse. A lot of Black people and people of historically excluded groups are walking around with PTSD.”

To help determine whether setting a boundary with someone might be necessary, Martin suggests asking yourself how being around that person makes you feel. “Pay attention to the emotional residue within your body after hanging out with someone,” she says. “If you feel sucky, try to figure out a way to decrease that. Also, still have faith in the fact that everyone and everything is not evil.”

Putting some distance between yourself and someone problematic is crucial for your own well-being. “Being in a constant state of stress — over [the election] or any other issue — is not sustainable,” Flint says. “Decide when disengagement is actually a self-care mechanism and employ your right to say enough for the time being.”

Boundaries are also vital as we navigate sadness, Metzger says. “We are already emotionally exhausted so our capabilities for others are lessened,” she explained.

Turn fear and anger into action

Those experiencing fear and anger should try channeling those emotions into something productive, like caring for yourself and others, Martin says. “I tell my patients to use everything: we do breathing techniques, and we talk about the impact of [what’s going on in] the world,” she explains. “And then I also say, ‘So, what do you want to do next?’ because part of mental health is also knowing that you have autonomy, and figuring out how you’re going to care for yourself in that realm.”

Taking care of others can mean donating to a food bank or therapy fund, or taking part in community organizing. As Martin points out, there will be plenty more to be fearful of and angry about in the next four years, and to combat that, we’ll need “to try to figure out some kind of buffer for the fuckery that we’re about to see.” So, get angry, then get to work.

“You have every right to be pissed off, but what are you going to do with it?” she asks. “You can tell somebody to fuck off while also donating to a therapy phone line. You can angrily crochet hats for unhoused populations. Anger does more than people acknowledge.”