‘It Was 46 Years Ago, But It’s Still Vivid’: A Jonestown Massacre Responder Speaks Out

On November 18, 1978, 918 members of Jim Jones’ Peoples Temple cult died in Jonestown, Guyana, in the single largest loss of American civilian lives in a deliberate act before 9/11. From the moment media coverage of the massacre began, much of the reporting has characterized the event as a “mass suicide,” in which people willingly drank cyanide-laced Flavor Aid when their leader instructed them to do so.

The reality of what transpired was far more nuanced — as was life in Jonestown since establishment of the failed utopian community in 1974.

Even as popular culture has slowly started to shift away from certain types of victim-blaming, Jonestown is still routinely presented as a situation where people consensually died by suicide. But a new three-part docuseries, Cult Massacre: One Day in Jonestown — which premieres on Hulu on June 17 and Nat Geo on Aug. 14 — takes a strikingly different approach.

Through archival video and audio footage and interviews with eyewitnesses and survivors, the series provides viewers with a glimpse inside the commune before, during, and after the massacre, from when it was founded as a refuge from capitalism and racism, to when the bodies of the deceased were transported back to the United States.

A few hours before the deaths of more than 900 people, San Francisco Congressman Leo Ryan — who had come to Jonestown to investigate alleged abuse of members — three journalists, and a Peoples Temple defector were killed in an ambush shooting on the Port Kaituma airstrip a few miles outside of the commune. Several other members of his party were wounded, but had survived by playing dead, or hiding behind the wheels of their Twin Otter aircraft.

The result is a complex, empathetic retelling that answers questions about why someone might join a group like the Peoples Temple, or move to a settlement in the Guyanese jungle in the first place, and makes the case that the deaths should be considered a mass murder — not a mass suicide.

The firsthand account of Ret. Gen. David Netterville — one of the first three U.S. servicemen on the ground in Jonestown following the massive loss of life — bolsters this argument. A sergeant at the time, Netterville was a combat controller with the Air Force Special Operations Division, an elite group of highly specialized soldiers that worked with the various branches of the military and Special Ops, similar to the Green Beret Special Forces, the Army Rangers, and the Navy SEALs. He had enlisted five years prior to making the trip to the Guyanese jungle.

While there is no shortage of documentaries about Jonestown, this is the first time Netterville is sharing his perspective on the aftermath. Rolling Stone recently caught up with him to discuss his experience at Jonestown, why he decided to speak out about it now, and what people still don’t understand about the massacre nearly 46 years later.

Where were you stationed when you got the call to go to Jonestown?

I was part of a 10-person combat control team out of Howard Air Force Base in Panama. I had been there since September 1977. We learned guerilla warfare, patrolling in the jungle, and did a lot of communications training. At that time, there were 12 of these teams in the entire Air Force; ours was the only one covering Central and South America.

In ‘77, ‘78, the Sandinistas were trying to overthrow the Somoza dictatorship in Nicaragua. [When I got the call to go to Jonestown] we had been on alert for two or three months to, at a moment’s notice, get on an airplane and go to Nicaragua to pick up U.S. embassy personnel and get them out — which we did the next year in ‘79.

How did you find out you were going to Guyana?

On November 19, [1978] I got a call about 7:30 in the morning on a Sunday. The phone was ringing off the wall, but I was sleeping, and wasn’t going to answer it. When I finally did, it was Senior Master Sergeant Alvin Huddleston, our noncommissioned officer in charge. He said: “I need you to pack a bag, go over to the armory, get some weapons, some radios, batteries, some water, some C-rations, and put them on the Jeep. We’re going to load the C-130 [military transport aircraft] as soon as possible, and we’ll be out of here.”

Did you have any knowledge of Jim Jones or the Peoples Temple before going to Guyana?

No, I’d never heard of it or him. I had been in Panama for a little more than a year at that point, and you lose track of things going on in the States.

A military air traffic controller directs a helicopter landing in Guyana.

National Archives and Records Ad

When were you told where you were going?

That morning I asked Huddleston if we’re going to Nicaragua. He said he couldn’t tell me because it was a classified mission, but he’d have more information once we were airborne. About 12:30 [p.m.] we were wheels up, and I’m trying to notice which direction we were flying out of Howard. Instead of turning north towards Nicaragua, we turned and went east.

An hour later, Captain Mike Massengale told us we were going to Guyana. I looked at Huddleston and Dalton and I go, “Guyana? Where’s Guyana?”

They tell us that it’s suspected that there’s a hippie commune in Guyana where mass killings are going on, and they’re fighting and shooting each other. They think there may be several thousand people there. So, I look at my two buddies and go, “There’s three of us, and there are a few thousand of them. This is really gonna be a tough one.”

Then we get word from the pilot that we’re going to land in Caracas, Venezuela to refuel. But we’d only been flying for two hours, and the C-130 can fly for around 10 [hours]. We’re told that we’re going to pick up some people and they’re going into Guyana with us.

They all come out dressed in nice suits. I was going to introduce myself and see who they are. Huddleston says, “No, don’t bother those guys. Leave them alone. They have nothing to say to you.” Now I’m really curious, and so I ask about them again. He says that they’re from another government agency — probably the CIA.

I did go over and asked ‘em a few questions and the first answer I got is, “You don’t have a need to know.” That’s their modus operandi.

Where in Guyana did you eventually land?

We left Caracas as soon as these guys got on board, and flew into Georgetown’s international airport. We offloaded our Jeep, trailer, and equipment and we’re sitting on the ramp. There was no one there to meet us. No information. There’s no telephones around. Nothing.

An Air Force C-141 medical evacuation aircraft was [at the airport in Georgetown] when we landed. It loaded the people that were wounded [the previous day in the Port Kaituma shooting] — like Congressman Ryan’s aide, Jackie Speier — and those who had died, [in order to bring] them back to the States. We tried to get information from the sergeant in charge [of the aircraft] and they didn’t know anything.

The captain in charge of the C-130 aircraft taxied over, refueled, and came out and talked to us. He says, “I’m going back to Panama — I don’t know what you guys are supposed to do.”

The three of us were just sitting there. Finally, a state department employee from the U.S. embassy comes walking up to us and he asks who we are. He didn’t know we were coming, so we introduced ourselves. He said, “Oh, I see you have a radio Jeep, yeah? Oh man, we can use you. Don’t go away.” And he walked off to go to a telephone.

Eventually, the State Department individual came back, and we locked the Jeep up in a hangar. We spent the night at his home in downtown Georgetown, trying to figure out how we’re going to get to Jonestown. The next morning we went back to the American Embassy for an intel briefing. They showed us pictures of what Jim Jones looked like, and told us who to look for.

Did you fly into Port Kaituma?

They had rented a Cessna 340 twin-engine aircraft. We flew an hour and 15 minutes to Port Kaituma, which is basically a dirt gravel strip about eight or 10 miles from Jonestown.

When we landed there, we saw the Twin Otter aircraft that got shot up, and met a small squad of Guyanese army soldiers. Then, a Guyanese army helicopter landed, but [the soldiers inside] didn’t know anything about us coming. We told them we were there to go into Jonestown and find out what’s going on, and they agreed to give us a ride.

It was just unbelievable — the carnage. The number of people laying on the ground.

When I first saw it from a distance — we were about five miles out — it looked like someone had scattered clothes all across the ground over about a two- or three-acre site. Colorful clothes, shirts and everything. I’m like, “Wow, look at all the clothes over there. They must have washed clothes.” I had never seen so many clothes. Never. When we got closer, I realized it wasn’t clothes — it was people. Corpses.

We landed in a softball field on the complex, got out, and started looking for anybody that survived. We were told there would be survivors, but didn’t see any that first time we got into the camp.

Did you ever find any survivors?

We flew back to Port Kaituma and ended up spending the night there in an elementary school with the Guyanese soldiers. While we were there, a guy came in. I think his name was Odell Rhodes, and he said that he was the camp medic. He had survived because when Jim Jones was having people injected with the cyanide, he sent Odell to the little medical hut there to get a stethoscope to make sure that they were dead.

Well, Odell said, “You know what? I knew I’d be next. So I hid in that medical clinic, I went out the back door, and I was gone. I stayed out in the jungle and followed the railroad tracks back over to Port Kaituma.”

He ended up spending the night with us there, sleeping on the floor of the elementary school. He left the next morning — there was a plane that came in and they took him out of there almost immediately. I never saw him again.

While we were there on the airstrip I saw another individual. This guy and his two daughters were in the jungle. He came out and he saw us and he ran back into the jungle. Later he comes out again, so I started hollering, “Hey, come over here! We’d like to talk to you! We’re United States Air Force!” He runs back into the jungle, hides behind a tree.

Finally, he comes out, walks over to us, introduces himself, and asks if we had any water. They had spent almost two nights out there in the jungle. So I said “Yeah, we got water. Hungry? We got food.” So he was a happy guy, but he’s still leery of us because of the weapons and everything. He was just scared to death because I mean, he’s witnessed the shootings and the people getting killed.

So once we got his confidence, he went back into the jungle and came out with his two teenage daughters. We give them some C-rations. We could just tell the trauma that they had been through. Not long after that, another airplane came in, loaded them up, and they were gone. We really didn’t have a chance to talk with them at all.

That day we flew back into Jonestown on the same helicopter.

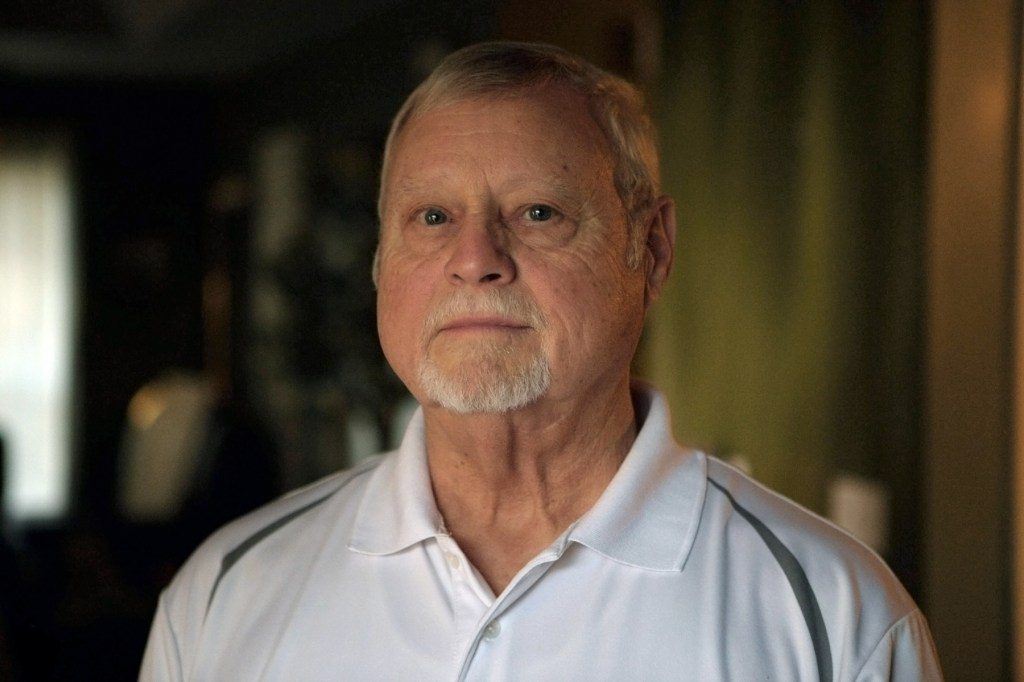

David Netterville was part of the first US Special Forces team to arrive at Jonestown to investigate the news of the attack to Congressman Ryan and his group.

National Geographic/Brandon Wide

What was Jonestown like when you returned?

It was hot and it was humid. We did have fresh water, though. Jonestown had artesian wells where they had put pipes and water was coming out. An Air Force surgeon came in the next day and they tested the water to make sure that we could drink it, and it was safe. It was real cold, and real good.

We were trying to find people that were still alive that maybe had survived. We walked around the edge of the jungle. Every so often we’d holler “Hey, is anybody here? Can you hear me?” Nobody.

Then Sergeant Dalton had the idea to count the beds in these little small wooden frame homes to find out how many people lived there. So we did, and there were approximately 1,000 beds.

While we’re there, another Guyanese army helicopter came in and had the Guyanese Surgeon General on board. I escorted him over to where Jim Jones was, by the bucket of Kool-Aid — actually, it was grape Flavor Aid mixed in with cyanide and some other things. He did a field autopsy on Jim Jones.

When he’s through, he asks what the three of us were going to do. He says that we need to do something with all these bodies. “I noticed there’s two bulldozers over there in the garage, and a couple of tractors,” he says. “What you should do is dig a gigantic pit, put all the bodies in there, cover it with lime, and just have a mass burial area right there.”

Now, you have to remember that by this time, these bodies were starting to bloat and the stench was terrible.

He said that he would highly suggest wearing a mask.

Well, there were no masks to be had, so I improvised. I went and got a pillowcase and I cut me out a bandana like a cowboy, and I wore that the rest of the time I was there. I’d soak it every morning with Old Spice aftershave. To this day, I can’t smell Old Spice aftershave. If I do, I throw up.

Peoples Temple founder Jim Jones is pictured in a family portrait with his wife, Marceline Jones, their adopted children (behind Jones) and his sister-in-law (right) with her three children, in California, 1976.

Don Hogan Charles/New York Times Co./Getty Images

I don’t blame you. Were you the one who identified Jim Jones?

The first people to actually find him was the Guyanese army. Jim Jones was shot in the head. Now, I didn’t see a pistol laying next to him, so I don’t know if he did it himself, or if one of his security guys had shot him. But he was laying on his back, right there behind his pulpit at the entrance of the Peoples Temple [pavillion]. He had on a bright red shirt, tan khaki pants. He was pretty easy to recognize.

What about everyone else?

Most people were laying on the ground on their stomach; many still had syringes stuck in the back of their neck. We also found people that had been shot in the head with a 38-caliber pistol.

Whoever was administering the syringes would just drop people right there as they died and stack [the bodies] on top of each other. Like, you’d have four or five people piled up. Unfortunately, I saw a lot of children — a lot of young children — one- and two-year-old kids that had a syringe stuck in their neck like that. It was terrible. Man, how could someone do this.

That’s why we didn’t know how many people there really were when we made the initial count. We were estimating 400, 450 from what we could count. We radioed that back on the high frequency radio, and they didn’t believe it. They didn’t want to believe it.

Were you tasked with counting the bodies?

No, that just happened. I don’t know exactly what directives came down to Sergeant Huddleston, but once we got there, we were trying to find people that were still alive.

Did you continue counting after reporting the initial numbers?

No. After that, a group of soldiers flew in to take over. It was a graves registration unit, and that’s their job, say, on the battlefield: they go out and recover bodies, put them in body bags, and then evacuate them.

What else did you come across during your investigation?

They had even shot all the animals: dogs, cats, in that little zoo there with a chimpanzee — I think his name was Mr. Muggs — shot him, shot two other monkeys in a cage. Man, they killed everything and everybody.

We did go over to Jim Jones’ house, and I took a crowbar from the workshed out there and pried open his safe. There were four, five, six boxes of passports and Social Security checks inside.

About this time, one of the CIA guys who came down on the plane with us walked in and asked what we were doing. We said that we were looking to see what’s in the safe. So he said, “Who told you to do it?” And we said, “Nobody. We’re investigating here.” You don’t know how bad I wanted to say “You don’t have a need to know, sir.”

He says that he’s got to take the boxes back. I said, “Have at it,” turned around and walked off. I left him there. I had other things to do.

What were your other responsibilities during the mission to Jonestown?

We found an observation tower and set up our radios to talk to any aircraft that may be coming in. It was right by the little building that we slept in — a little hooch [temporary shelter] — and so we set that up as our command post, and we did all our air traffic control out of that tower.

Once I got in that tower, I was talking to 200 or 300 airplanes every day coming in and out of there. If it wasn’t one of the military guys, there were a lot of news people that had rented airplanes, and I was trying to keep all those guys separate — you know, vertically.

How long were you in Guyana?

We were there seven days total; we got back to Panama on the eighth day.

Why have you decided to speak out about your experience now?

I think it’s just timing. [In 2019] I gave a talk at an [Arkansas] college, and I’ll be honest with you — I found that by talking about it, I don’t have to worry about it anymore. It used to really bother me. The thing that bothered me the most was the children. I don’t know the exact number, but something close to 150 [of the dead] were young kids aged 10 and under. It was pretty horrendous.

I imagine you carried that trauma and story with you?

Oh yeah, for decades. It was 46 years ago, but it’s still pretty vivid. I remember walking through the camp having to step around dead bodies. It was unreal.

What do you wish people understood about Jonestown, nearly 46 years later?

The church that Jim Jones had in San Francisco was actually under investigation for stealing people’s money, taking their homes, stuff like that. He probably brainwashed a lot of these people. He had some of them actually believing that they should all die and go to heaven together.

And the people that didn’t [willingly ingest the poison]? Well, they ended up getting shot, or being held down while someone stuck a syringe in the back of their neck. Once it got going, people were dying left and right. There’s really nothing they could do.