Inside Snapchat’s Teen Opioid Crisis

A

lex Neville was one of those boys who was always in costume, wearing his obsessions on his sleeve. At three, he went around dressed as a mummy, earnestly explaining the embalming process to children in Aliso Viejo, a town in Orange County, California. At seven, he was SoCal’s shortest Civil War junkie, dragging his father to local reenactments of the Battle of Gettysburg. It was at one of those events that he met his great hero: a tall, bearded schnook playing Abe Lincoln. “Alex was speechless when he shook ‘Abe’s’ hand,” says his father, Aaron Neville. “For him, it was like meeting Beyoncé!”

But for all his little-professor chi, Alex was a boy’s boy through and through. He ran with his wolf pack of free-range kids from kindergarten on. They boogie-boarded riptides and stunt-jumped skate bowls, anything for a G-pass from gravity. It was hard being one of the brightest kids in class, though, when his brain kept overheating. “We knew two things about him early on,” says his mom, Amy Neville, a heart-faced woman with the watchful zen of a longtime yoga instructor. “One, he was borderline genius — at least. Two, he had ADD. Or something.”

Alex couldn’t sit still or manage his moods; the smallest things triggered eruptions. “As we found out from his therapist, he had a ‘ring of fire’ brain; it never switched off,” says Amy. Alex lived at the whims of his central nervous system, and the first thing that tamed it was weed. “He smoked in seventh grade. For him, it was like, ‘Where have you been?!’”

How does Amy know this? Because Alex told her everything that passed between his ears. He gave his mom the blow-by-blow on his middle school romances. When he broke his word and smoked weed again, he confessed that, too. And when weed wasn’t enough, and he bought his first pills online, then got hooked on what he thought was Oxycontin, he went to his terrified parents and told all: A dealer I met on Snapchat. He taught me to use PayPal. I’ve been using for the last seven days.

Amy Neville spent that night and the next day, too, trying to book her son a rehab bed. But this was 2020, three months into the pandemic; no one was going anywhere overnight. The following morning, he had a dentist’s appointment. Neville opened his door and found him sprawled on his beanbag, his left hand tucked in his waistband. There was vomit on his shirt, and his lips were blue. Alex Neville — age 14, a freshly minted eighth-grade graduate — had been dead for at least six hours.

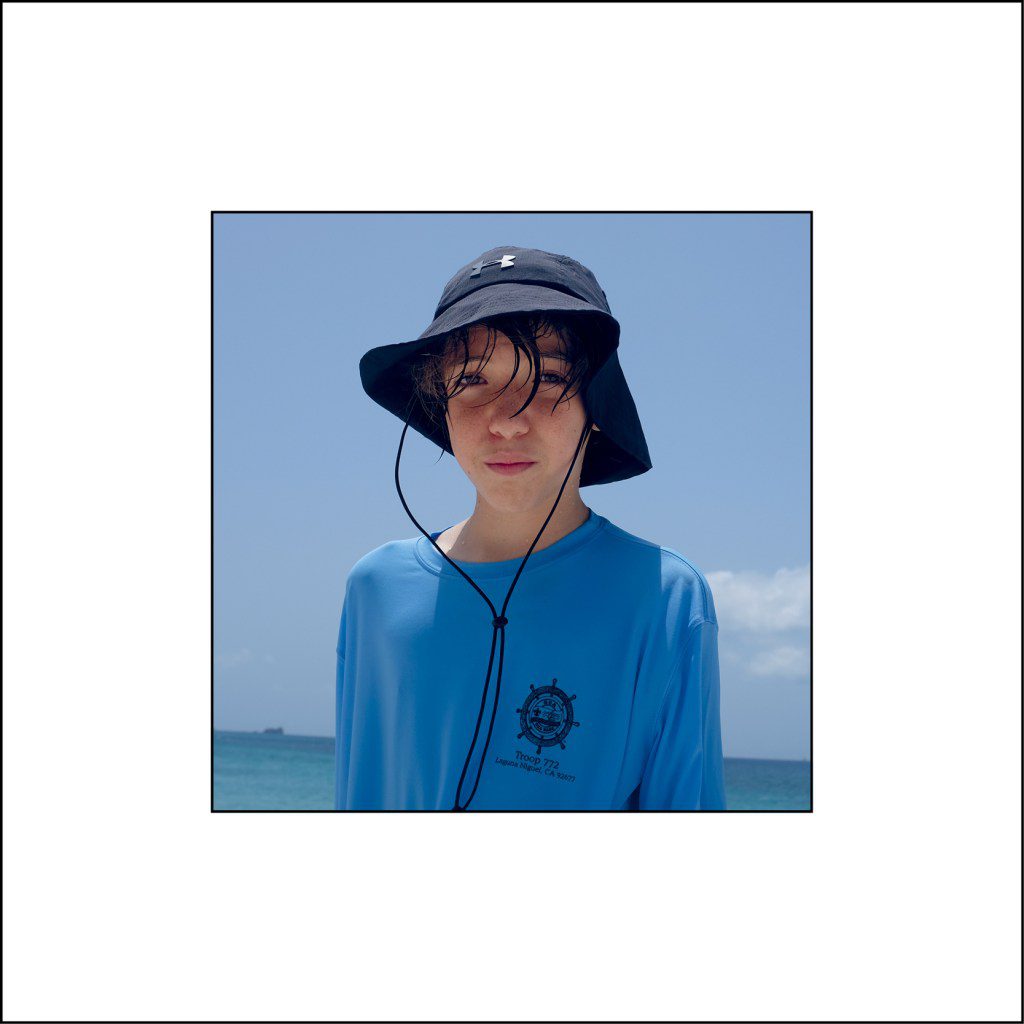

ALEX NEVILLE

Before he OD’d at 14, Alex told his mother he’d met a dealer of prescription pills on Snapchat.

Courtesy of the Neville Family

Soon, Neville’s house was aswarm with cops. One of them found a vial with seven blue pills in a box on Alex’s nightstand. They field-swabbed the residue, then explained to Amy which poison had killed her child. Fentanyl from China, by way of someone’s basement. Mixed by dealers in $30 blenders that leave chunks, or lethal “hot spots,” in the pills.

For weeks thereafter, Neville stumbled through fog. She shut her yoga studio and sat alone with her sorrow, unable to pull truth from facts. How could a kid so loved and alive get addicted to a surgical anesthetic? Sheriff’s deputies had no answers, and the DEA wouldn’t comment. So Neville got off her couch and started digging.

The first clue came from a girl Alex knew. She hadn’t met the dealer, but she’d seen his online handle: He went by AJ Smokxy on Snapchat. Other friends in middle school copped from him, too; he’d deliver the pills right to your door. The next penny dropped when a ping came in on Facebook. I know who killed your son, said the stranger. It’s the same guy on Snapchat who killed my Hector.

The sender was a bereft mom named Valerie Bradley. Her son Hector OD’d on July 7, 2020, two weeks after Alex passed. Bradley sent Neville screenshots of texts Smokxy had posted to Snapchat. The first was Smokxy ranting that he’d only sold Alex weed, not pills. In a second text, he denied killing another kid two weeks before Alex died. That seemingly made three boys dead in four weeks. Neville sent those details off to Dave Mertus, the DEA agent working on Alex’s case. She waited for his call, or for news of Smokxy’s arrest. Nothing. Just the screaming in her head.

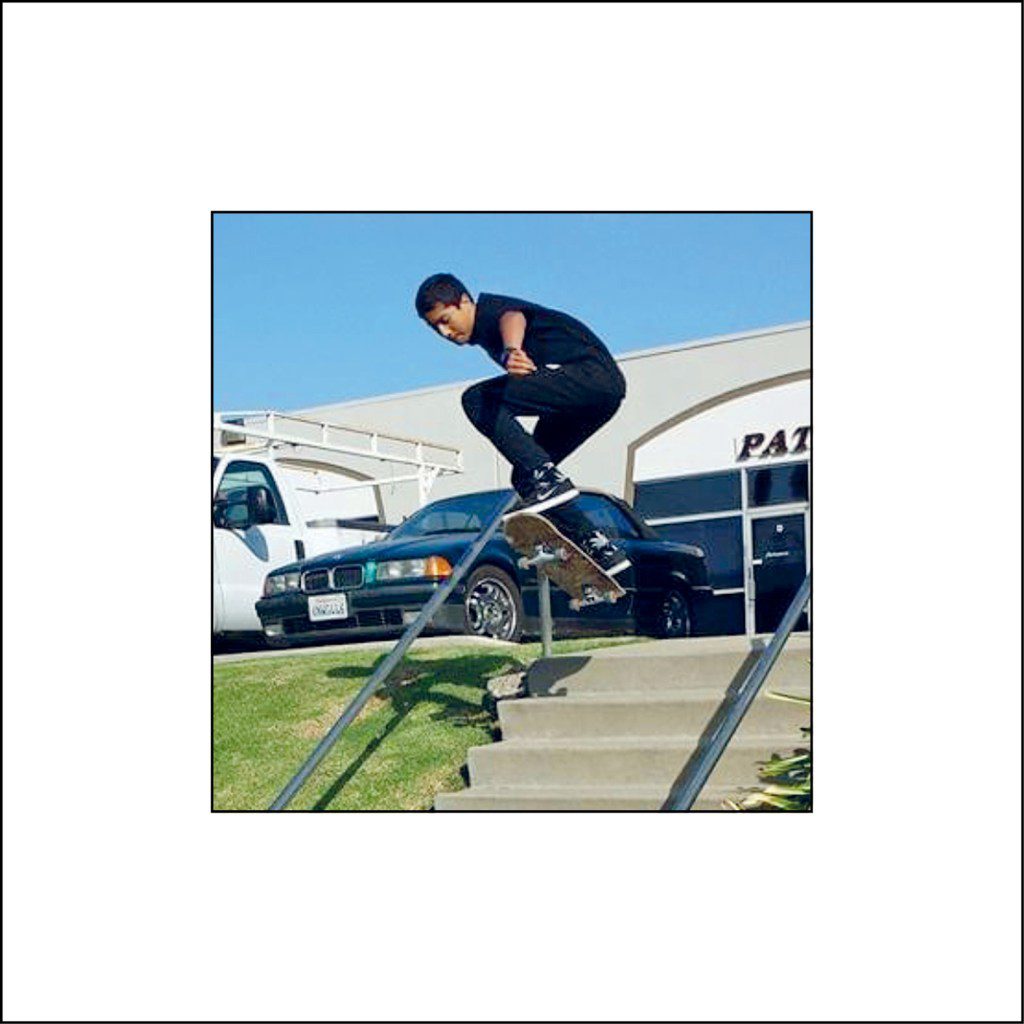

HECTOR BRADLEY

He died of an OD two weeks before Neville; Bradley’s mom believes the same dealer sold them fake pills over Snap.

Courtesy of Valerie Bradley

Meanwhile, children went on dying. A school friend of Alex’s, 15 and pretty, died seven miles away, in her bed; a fentanyl pill bought online. Three kids from the local high school were killed in 13 months. Cause of death: fake pills bought online. That fall, Neville went to a survivors’ conference in Ohio, and says she met parent after parent of SoCal kids allegedly poisoned by Snapchat dealers. They’d drowned in that first tall wave of overdose deaths: More than 950 kids killed in 2020, 70 percent of them felled by fentanyl and other synthetic drugs; 1,150 more died in the first six months of 2021, three-quarters of those deaths from fentanyl and synthetics.

Between 2019 and 2021, the number of teen deaths from fentanyl tripled — and the driver of that plague, per the cops and feds I talked to, was fake pills sold online. Phony opioids that looked like Oxycontins but were cut with fentanyl, not oxycodone; bogus Xanax but with fentanyl, not alprazolam, on board. Name any pharmaceutical with a foothold on campus — Adderall, Valium, Suboxone, what-have-you — and it was instantly available via social media and delivered to your door like Papa John’s.

The folks compounding those pills weren’t pharm-school grads. They were cartel adjuncts or lost-soul dropouts with a storage unit and a pill press. And whether their fentanyl came from Mexico or directly from China, they were everywhere and nowhere at once: invisible on the street but ubiquitous online; and many were hawking poison disguised as pharma drugs over Snapchat.

‘If you’re a fake-pill dealer, where would you rather work?’

Meanwhile, no one seemed to be doing a damn thing about it. The DEA didn’t launch its first PSA alert until the fall of 2021, and local cops walked away, or made half-hearted searches of a deceased kid’s phone for actionable links to the dealer. Those links were long gone, though, scrubbed minutes or hours after the last exchange between seller and buyer. That, Neville learned, was why the dealers had moved to Snapchat: It was effectively a safe space for them. All forensics vanished within 24 hours, wiped clean by the delete function of the app. That wasn’t a bug but a feature of Snap, the code choice that sent its fortunes soaring and marked it out from its social media rivals. On TikTok and Instagram, your DMs and photos largely lived till you deleted them, one by one. On Snap, it was the reverse: Everything turned to smoke unless you manually saved it to your account.

This was manna for kids, who could text (or sext) each other without fear of their parents’ prying eyes. But that disappearing ink was a godsend for dealers too — a chance to sell narcotics and leave no breadcrumbs for the cops and feds to follow. This made all the difference to fake-pill pushers, whose product was as lethal as it was deceptive. Two milligrams of fentanyl — think 10 grains of salt — would asphyxiate a teen in his bed. Why fentanyl? Because it’s so plentiful and potent that you can produce a fake Oxy for less than five cents a pill — and sell that pill to kids for $30. Dealers, as a rule, don’t try to kill their clients, but with fentanyl, it’s the cost of doing business. No home cook can process a batch of “Xanax” without peppering chunks of fentanyl in the mix. Those chunks get pressed into the random pill — or half-pill, as sometimes happens. I know of one kid who split a “Percocet” with his girlfriend, then suffocated while she slept soundly. Per the latest report from the DEA, roughly 70 percent of the fake pills seized by agents contain fatal doses of fenty. For every pill they flag, though, many more get through and wind up for sale online.

To be sure, dealers hawk their poisons on all the social apps, but, law-enforcement sources say, they commonly sealed the deal on their Snapchat account because of its clandestine features. The app largely shields them from undercover cops posing as teenage buyers and affords them further safeguards like the Snap Map feature that shows them, in real time, where a kid is waiting. There’s also an in-app alert that warns the dealer if a kid has tried to screenshot their chats. “If you’re a fake-pill dealer, where would you rather work? On a platform where they destroy all evidence of your crimes, or on TikTok, where they keep and archive that evidence in case law enforcement calls?” says Bill Bodner, the recently retired boss of the Los Angeles field office of the Drug Enforcement Administration. “I spent five years trying to get something out of Snapchat. Not once did they come across with something useful.”

Moreover, says Bodner and a dozen sources in law enforcement who talked to me for this story, Snapchat seemed to slow-walk police investigations after fake pills killed young buyers. Court orders and subpoenas sat for weeks and months with Snap’s law-enforcement team. What data Snap disclosed, after long delays, proved useless, insufficient, or both, according to law enforcement. Such was the feds’ frustration with Snap that a top official at the Department of Justice called me last summer with an urgent plea. “We’ve heard from too many parents whose kids were poisoned — and none of those kids knew they’d bought fake pills.”

Over eight months reporting the facts of this story, a week or so working on a documentary with grieving parents that was just as quickly shelved, and five months of pressing Snapchat officials for frank answers to pointed questions, I’ve come up against two mutually exclusive accounts. There’s the heartsick version told by parents, cops, and lawyers about anxious kids without a lick of street savvy who bought pills from a stranger on Snapchat and died 20 feet away from their mother’s bedroom. And then there’s the version told by Snapchat: That it has strenuously enforced a zero-tolerance policy regarding drug dealers and their poisons; that since 2014 its trust and safety teams have worked tirelessly to protect their users; and that since fake-pill dealers surged to the socials at the start of the pandemic, Snap has done everything in its mortal power to partner with law enforcement. Bluntly put, there’s no common ground occupied by these parties. What follows are the facts as I found them. To begin, here’s Snap on the feds’ contention that the platform has been a hub for fake-pill dealers.

“We are heartbroken by this terrible epidemic and … are deeply committed to the fight against fentanyl. We’ve invested in advance technology to detect and remove drug-related contents, worked extensively with law enforcement to bring dealers to justice, and continue to evolve our service to keep our community safe. Criminals have no place on Snapchat,” said Jacqueline Beauchere, Snap’s head of global platform safety.

But when pushed for specifics — which cops or federal officers had Snapchat “work[ed] extensively with,” which drug dealers had they helped bring to justice? — Snap said, “The law requires us to respond to subpoenas and search warrants according to a detailed process, which we acknowledge can be frustrating for law enforcement and our team. If we don’t follow the process, the evidence we provide could become inadmissible, and that’s not an outcome any of us want.”

I spent five years trying to get something out of Snap. Not once did they bring something useful.

—Bill Bodner, former head of the Los Angeles division of the DEA

Now, up against a firm with tens of billions, most parents would have let the matter lie, going back to tend their shattered families. Not Neville: She mustered an army of grieving parents through a series of Zooms and meetups. She flew around the country, pumping online watchdogs for everything they knew about Snapchat. She sat with U.S. senators and Department of Justice staffers, asking why a company was allowed to shield the dealers who were hurting or killing children. There’s not much we can do, said the Beltway folks. “Snap’s protected by a law from 1996 — and no one’s been able to touch them,” she paraphrases. Section 230c, a 26-word addendum to the Communications Decency Act, gave social media companies broad-strokes immunity from crimes committed by their users. Time and again, they’d been sued by the victims of revenge porn, extortion, and cyberstalking. Time and again, those claims were tossed by judges citing Section 230. No industry in America had such far-going protections — despite stacks of reports that Snapchat, Meta, et al. were enabling bad actors to commit harms against young users.

But with all this massed against her, Neville pressed ahead. “Someone had to hold those people accountable,” she says of Evan Spiegel and Bobby Murphy, the former wonder boys from Stanford who founded what would become Snapchat off-campus in the summer of 2011. “If they’d just done anything to show me they were human, I’d have backed away.” Instead, in 2021, they tapped a stand-in to Zoom with Neville and a handful of other parents who’d lost children. Neville says that senior executive badly misread the room. Per Neville and other parents on the call, the executive minimized its role in the overdose crisis, saying Snap — worth more than $50 billion at the time — was just a small company and only now learning about this problem. Neville sat there, speechless, feeling her fury cook. “It wasn’t just ‘no,’” she says. “It was, ‘We don’t even see you tiny ants.’”

(Snap’s response, via Beauchere: “We are grateful for the opportunity to listen to families who have shared their stories and offered feedback on how we can help keep our community safe. We have met with Mrs. Neville on two occasions in addition to communicating on the phone and via email, and we would never attempt to minimize her important story.”)

In the spring of 2021, Neville found a law firm, C.A. Goldberg, to take her case and those of six other families. They’ve since added a second firm and dozens more families, and their long-shot civil case beat the odds. Around six months ago, a California judge gave Neville and her peers the ruling they’d prayed for: access to Snap’s internal data. That ruling has been briefly stayed, pending Snap’s appeal. But if upheld, Neville’s lawyers will comb through Snap’s files, establishing what, and when, its leaders knew regarding drug dealers and dead kids. Things could get ugly fast for Messrs. Spiegel and Murphy. Whatever the outcome, this much is certain: They messed with the wrong mother and found out.

‘The best way to sext’

Sometime in the spring of his junior year at Stanford, an English major named Reggie Brown had a lucrative revelation. Brown, per several reports, was sending phone pics of himself to a girl he knew — and wished he could make them vanish once she got them. He bounded down the hall to share his epiphany with his Kappa Sigma frat bro, Evan Spiegel. “We should make an [app] that sends deleting-picture messages,” said Brown. Spiegel, a 20-year-old raised Hollywood-posh — his parents’ divorce suit and an L.A. Weekly feature reveal he attended the same prep school as Judd Apatow’s kids; threw Gatsby-size parties at his father’s mansion; and drove both a new Escalade and a Beamer in high school — knew a lottery winner when he heard one. “That’s a million-dollar idea!” he told Brown. The two friends quickly found a third, Bobby Murphy, to write the code for their creation. They repaired to L.A. when the school year ended, moving in with Spiegel’s father, a securities lawyer.

There, they divvied up the jobs and titles. Spiegel, the CEO, designed the app’s features. Murphy, the tech chief, programmed the site, and Brown, the chief marketing officer, wrote up everything else, from press releases to terms-of-service language. The purpose of the app seemed plain enough: Their press draft cited campus “betches” and the perils of “incriminating photos.” “[Without Snapchat], a betch would be at the mercy of her captor if anyone got hold of her phone.” Spiegel pitched his product to a female blogger, writing, “Gurl, I just built an app with two … certified bros that I think you’ll really like.” “Aah,” she replied, after feeling it out. “So it’s like, the best way to sext?” Spiegel responded: “Lucky guess.”

Spiegel — the youngest billionaire on the Forbes World’s Youngest Billionaires List four years after Snap’s launch — has since walked back the smuttiness of its birth. “I just don’t know people who [sext on Snap]. It doesn’t seem that fun when you can have real sex,” he told TechCrunch back in 2012. One of Snap’s spokespeople met me for breakfast and tried to dissuade me of any vulgar misconceptions. “When Evan and Bobby [Murphy] created Snap, they and their friends felt they had to perform to get noticed [on social media],” she tells me. “They were like, ‘Why can’t we have a place that’s oriented around talking to friends the way you do in real life?’ Our messaging is ephemeral because people are more comfortable sharing life’s moments … when they’re not recorded permanently … for the world to see.”

In response, I raise Spiegel’s emails, written to his frat brothers shortly before he founded Snapchat. To be sure, he was 19 or 20 when he sent them, but their baked-in misogyny digs deep:

Hope at least six girl [sic] sucked your dicks last night … Fuckbitchesgetleid.

Have some girl put your large kappa sigma dick down her throat … can’t wait to see everyone on the blackout express.

I wonder if my TA has ever been peed on. She’s pretty hot for a Tri-Delt.

—Evan Spiegel

The spokesperson referred me to Spiegel’s apology after the emails were leaked in 2014. “I’m obviously mortified and embarrassed that my idiotic emails during my fraternity days were made public…They in no way reflect who I am today or my views toward women.”

Those emails, dumped to Valleywag, an erstwhile tech blog, surfaced a year after Spiegel and Murphy were sued by Snap’s co-founder, Reggie Brown. There’d been an ugly rupture in the summer of 2011: Brown stormed off after overhearing his partners plot to oust him. He soon filed a lawsuit and brought receipts, including a text from Spiegel that seemed conclusive: “I want to make sure you feel like you are given credit for the idea of disappearing messages.”

Through their lawyers, Spiegel and Murphy rebuffed Brown’s claims. So the suit slogged ahead, creating a public record of Snap’s contentious founding. When paired with a second batch of court filings — the transcripts of his parents’ lavish divorce — a sense of Spiegel emerges as a shark-toothed chancer in a rush to build an empire by 25. As he’d later tell young aspirants at Stanford, “It’s not about working harder. It’s about working the system.”

Much of what we know of Spiegel stems from those two lawsuits — including the cost of settling with Brown. As reported by Snap to the Securities and Exchange Commission when the company went public in 2017, Spiegel and Murphy paid Brown around $158 million to renounce his equity bid. It was the largest sum paid to a tech-bro founder since the reported $65 million that Facebook paid the Winklevoss twins to fuck off. Between the dump of his college emails and the check he sent to Brown, Spiegel got a crash course in crisis management before he turned 25.

BEARING WITNESS

Spiegel (right) at a congressional hearing in January, with parents protesting behind him

Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters/Redux

What’s past dispute, though, is his business savvy: Spiegel is a genius at making markets. In the fall of 2011 — per a Forbes report — Spiegel scanned the metrics on Snapchat usage and saw it peaked between 9 a.m. and 3 p.m. His core customers, he surmised, were schoolkids, not frat boys sending ghost pics of bongs and boners. Rather than course-correct, he seemed to steer straight for it, developing features that ensorcelled a generation: Filters that morphed kids into kittens and ponies, and allowed them to “swap” faces with their friends. Wallpapers that placed them in Paris and Vegas, plus a sweet-shop selection of hearts and starbursts to glow up their giddy shots. Kids were using their phones to make art, or at least menagerie, of selfies. They could play with each other, online and in life: Snap Map, launched in 2017, showed them where their friends were skating, or where the party was on Friday night.

Best of all, kids could climb the ladder on Snap, posting content that earned them clout with other teens. Sending lots of Snaps boosted a kid’s Snap Score. That fast became a badge of social capital; the higher your Snap Score, the more juice you had with your Snap friends, real and virtual. It was also a strong incentive to accept friend requests from people you’d never met. Kids got Quick Add suggestions from Snap that were culled from their contacts. But a second batch were users with no obvious linkage — and some of those strangers harbored bad intentions, say Neville’s lawyers in courtroom affidavits.

“During the period of our lawsuit — 2019 to the present — Snap was pushing Quick Add strangers by the hundreds to young kids,” says Laura Marquez-Garrett, a senior attorney at the Social Media Victims Law Center (SMVLC), the law firm suing on behalf of Neville and 63 other families. “We tested it ourselves, posing as 16-year-olds on three new burner phones. On two of them, we got a Quick Add screen with hundreds of ‘friends’ we didn’t know.” Men with pill or dick emojis in their handles, and women with dollar signs, says Marquez-Garrett. “We tried to steer away, but a screen popped up that said ‘Interacting with friends is what Snapchat’s all about. Are you sure you want to skip this step?’” Their firm filmed step-by-step footage of those sign-ups and submitted the

reels to court.

One of Snap’s motives for pushing Quick Add suggestions was to maximize the time kids spent on Snap, claims Marquez-Garrett. But the kids who friended a dealer through Quick Add suggestions were exposed to many others — and vice versa, per Marquez-Garrett. “Once a dealer gets connected to a kid, it opens all that kid’s contacts to him, too.”

Snap’s response? “Snapchat was built to help people communicate with their close friends and family. Our goal is to make it as hard as possible for a bad actor to find and contact a teen … and we continue to roll out new protections to mitigate unwanted contact and prevent the discovery of potentially harmful content.”

In reporting this piece, I talked to a dozen or so kids about their experience with Snap. The older ones acknowledged getting Quick Adds with strangers, but said that happened on other apps, too. And yes, they knew Snap was fraught with drug content, but many including Jackson, a college freshman in California, “only fucked with the people selling weed there.” Mostly, they spoke about how central Snap was as a touch point to their friends. “You literally can’t function without it,” says Katherine, a college-age kid in Massachusetts. “It’s how we talk to each other. You’d be totally nowhere without it.”

Younger users lapped up its fun-house features and spent hours on it horsing around. “I like it ’cause the lenses give you big, giant eyebrows, and make your jaw two feet long,” says Sophie. Her twin, Brooklyn, had a crush on Snap’s AI, dressing his avatar in Jordans and a backward baseball cap. “Then he sent me a text saying, ‘I’m uncomfortable being called ‘boyfriend,’” Brooklyn says. That didn’t hurt my feelings, though. He’s only a machine.”

It bears saying that Sophie and Brooklyn are 12 years old and opened their Snap accounts when they were nine. Snap forbids that; the minimum age for sign-up is 13. This problem is not specific to Snap: None of the socials require proof of age or demand parental consent. But no other firm has chased the youth demo with the single-mindedness of Snap. By the start of the pandemic, per Tech Policy Press, 92 percent of Snap’s user base was between the ages of 12 and 17. Riding that demographic, Snap aimed for the stars and achieved escape velocity fast. It went from 20,000 users in those first few months to more than 140 million in five years. (Mark Zuckerberg offered Spiegel $3 billion to take Snap off his hands in 2013. Spiegel turned him down.) Per Reuters, last year, Snap earned $4.6 billion; Spiegel’s net worth was $3.6 billion at press time, according to Forbes.

But by the summer of 2021, Snap was battered by bad PR. Fake-pill poisonings traced to Snapchat dealers made the local and national news. Bereaved parents sobbed on the Today show and Dr. Phil, singling out Snapchat for their loss. Families with signs and bullhorns marched on Snap’s office in Santa Monica, calling for Spiegel’s arrest. Once the online playground for tweens and teens, Snap was now the Big Tech face of the fake-pill plague. Its executives were hauled in front of Congress to explain why young users were dying. Multiple laws were pushed by a Senate subcommittee to hold Snap and its rivals accountable for harming kids. (Mired in political quicksand, none of those bills have come to votes yet.) And several other lawsuits besides Neville’s trundled toward court, seeking damages in the untold billions from Snap and the other social media giants for “fueling the nationwide youth mental health crisis,” per New York City’s Mayor Eric Adams.

Covid drove dealers online, because that’s where the kids were. And Snap was the top spot. —Bill Bodner, former head of the DEA in Los Angeles

To be fair, other platforms hosted millions of kids, too, and were beset by dealers and their pills. And consider the sheer scale of Snap’s safety challenge: Each day, 5 billion posts are exchanged by its users, or more than 2 million a minute. But crimes done on TikTok left durable tracks for law enforcement to follow. On Snap, the trail was faint and short-lived. According to multiple law-enforcement sources, between 2019 and late 2022 — the years of inquiry in this story — that vanishing ink was a stone wall for cops, and a boon to Snap’s criminal users. Dealers plastered menus of their pills and prices on their public-facing Stories page. They posted up in places where kids hung out and pinned menus to their Snap Map tabs. Up popped the profiles of Snap users nearby — and an easy way to tell kids from cops.

“All you have to do is look at their Snap Score: No cop could build a Score in the six figures,” says Bodner, the former DEA chief. Bodner was there at the birth of the fake-pill epidemic. His team bagged its first major supplier in 2016, and a second one two years later. He and his agents have been to dozens of houses where children died in their beds, racing the clock to crack the victim’s phone before his Snap texts disappeared. “You’ve got a very short window, unless the kid and dealer switched to [standard] texts to finish the buy,” Bodner says.

In 2017, multiple mainstream outlets sounded the alarm about Snapchat. An undercover reporter for the BBC met dealers making thousands of pounds a day selling drugs to schoolkids on socials. “I fear it is going to take something very tragic … before Instagram and Snapchat wake up,” said the reporter, Stacey Dooley. Corroborating accounts in The Guardian, The Mirror, and on Fox delivered the hard news to Snap’s doorstep. Snap’s response? Rote statements about its “zero-tolerance policy” and its “dedicated Trust and Safety Team.” The press kept ringing Snap’s bell and found no one home.

Pressed about those statements, Snap says: “Snapchat has always had policies that prohibit using our service to try to sell illicit drugs. During the early days of the pandemic, society as a whole … was learning about the more recent and growing epidemic of dealers selling counterfeit pills. We were working vigorously, around the clock, to improve our tools and systems for fighting it.”

Still, say my sources at the DEA, Snapchat teemed with dealers, large and small. “We saw fake pills on socials before the pandemic, but Covid drove all the dealers online, because that’s where the kids were,” says Bodner. “Snap was, by far, the top spot for dealers — and once they saw how easy it was, they just never left.”

Pharma-Master and Oxygod

Years from now, when researchers write the history of the fake-pill wave, they’ll do well to park themselves in Salt Lake City and parse the case notes of Detective Dennis Power. A narcotics cop of 20 years’ distinction, Power was on loan to a DEA task force in Utah when he caught a lead in 2015: A series of small parcels from a distributor in Shanghai were being shipped to more than 20 addresses in town. One of the parcels ripped when it passed through U.S. customs; agents opened it and found 100 grams of fentanyl. They flagged the distributor and alerted the Utah task force; Power ran the names of the local recipients. None of them had rap sheets or hung out together. Their only connection was a man named Aaron Shamo; he either picked the parcels up or they brought them to his house, a nondescript one-family in town.

Then Power, who’d worked the case for the best part of six months, got the tip of a lifetime. His source was a guy he’d busted who was hoping to cut a deal. “He says, ‘I don’t just get packages and give them to Shamo. I drive out to the suburbs and pick up a bunch of boxes [from a house], then drop ’em in a different P.O. Box each day.’”

Power alerted his boss; agents scrambled to tail the runners. One of them followed Shamo out of town, to a posh suburb called South Jordan City. He saw Shamo pull a duffel bag from his trunk and plunk it into the trunk of a second car. Shamo drove off, but another agent hung behind, staying on the car with the bag. Not long after, a woman came out of a house and dragged the heavy duffel up her front steps. That night, Power’s informant got a text: The boxes are ready for pickup on the porch.

The snitch collected the boxes and brought all 79 of them to the station. “We open them up, and every fucking jaw drops: There were a half-million pills on that lunch table,” says Power. Fake Xanax and Oxycontins, most derived from fentanyl but a dead-perfect match for the drugs they purported to be. That head-smacking haul — worth $15 million on the street — represented two days of work by one man. Later, when agents hit Shamo’s house, they found him in his basement. Two pill presses the size of fridges were ka-chunking out tabs marked “M 30” — the stamp you’d see on an Oxycontin 30.

Pharma-Master; Oxygod

Weber County Sheriff’s Office; U.S. Department of Justice

Power sizzled with shock. Here, in the middle of white-boy nowhere, he’d stumbled onto a merchant of mass extinction: a handsome former Mormon who’d dropped out of college, quit his dead-end job at eBay, and become the dark-web kingpin called Pharma-Master. In the months to follow, they’d trace those fenta-pills of Shamo’s to dozens of deaths around the country.

The story of Aaron Shamo marks an inflection point in America’s War on Drugs. For the first 50 years, the enemy was external, or so we were told by the authorities. Mexico, Colombia, Bolivia: The cartels were the cause of all our woe — and never mind that they didn’t put a gun to our heads and make us the world’s thirstiest users of narcotics. Then, quietly, with no great effort or plan, America’s millennials got in the game. In the middle of the last decade, kids with factory jobs and limited prospects found their way to the dark side: specifically, to a site called AlphaBay. Launched in 2014 by a Canadian coder named Alexandre Cazes, AlphaBay wasted not a single second becoming the foremost dark-net market for criminal commerce.

“Sex traffic, murder for hire, exotic animals, drugs: You name it, it was for sale there,” says Ray Donovan, the recently retired chief of the Special Operations for the DEA worldwide. “Kids in their teens would log onto Alpha, go to the chat rooms for fentanyl dealers, and order up a key of pure from Wuhan.” Days later, they’d find a brown box sitting on their doorstep — brought by that great new drug mule, the U.S. Postal Service. Here was Shamo’s ticket, and he cashed it hard, becoming one of the biggest vendors on AlphaBay in a hurry. When the feds swept in, garbed in Tyvek suits, they found more than a million dollars, cash, in Shamo’s sock drawer, and many millions more in his Bitcoin wallet.

Shamo was convicted of a kingpin charge and sentenced to serve life in federal prison. Cazes, the AlphaBay founder, was hunted down and captured on a quiet block in Bangkok by the Royal Thai Police in 2017. Right before he was extradited to the U.S. for arraignment, Cazes was found dead in his jail cell. By then, though, Shamo was a dark-net totem, the model for aspiring dons in every suburb. One squad tells me they staged two career busts in the span of 25 months. “Stacy” and her team (they’re still active agents, so they can’t be named in this piece) nailed the biggest dealer in SoCal in 2016. “Initially, we thought he was just making Molly,” says Stacy. “Then we raided his lab and found five industrial presses going at once.”

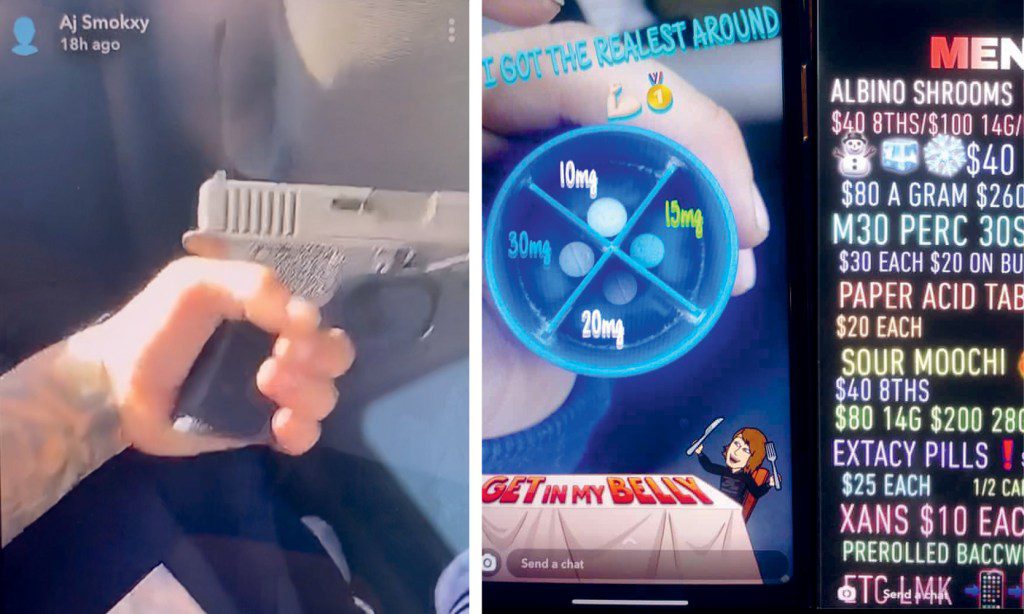

AJ Smokxy flaunting his lifestyle on social; dealers’ pages on Snap

From right: Social Media Victims Law Center, 2

Their next arrest made the bigger splash, however — if only for the arrestee’s clout on socials. In a past life, Wyatt Pasek could have been a boy-band star: He was a leaner, sulkier version of Nick Carter. But to fund his studio sessions, he sold fentanyl, says Stacy. He was at it “three years before we nailed him.”

By then, he was known by his new persona: the Lambo-driving don called Oxygod. There he was on TikTok, kicking back in a bathtub overflowing with hundred-dollar bills. There he was again, fanning bricks of cash on the hood of his tricked-out rides. Pasek got nearly 18 years of fed time, or roughly as long as he’d been alive. It was when he went to prison, though, that Pasek lived out his dream: to influence a generation of kids. The dark web “went crazy when they read our [indictment] affidavit and saw all the mistakes that Pasek made,” says Stacy. “They posted tips on Reddit that they gleaned from his screwups — and that definitely inspired [a second wave of] kids to get into the business of [online] drugs.” Except that those kids didn’t skulk around on AlphaBay. Instead, they hawked their goods on sunny, spangled Snapchat.

There, according to the DEA, they had company — and competition. The cartels, who’d been trucking over fentanyl bricks, “saw what these kids were earning on socials and got heavy into the pill game, too,” says Donovan, the former chief of Special Operations at the DEA. “A key of pure fenty was $3,000 wholesale.” But that same key made as many as 500,000 pills that sold for $30 apiece. “Next thing we know, the cartels are only sending pills and marketing them over the apps. Open-source socials became the sales hub for fenty — and Snapchat was, by far, the most prolific.”

‘A safe haven to sell drugs’

In his last days, Alex Neville did what most teens were doing during those mass-confinement months of early Covid: He tagged in with his locked-down tribe on Snapchat. For his generation, Snap was the grapevine; every thought or face-plant was posted there. Where’s the hang tonight? Who’s hungry for Chipotle? Anyone know that new girl in the Dunks? To reassure his mother, Alex showed her his phone whenever she asked to see it. “I’d go through his socials looking for sex stuff and bullies,” says Neville. “You know: the threats we were warned about online.”

Like each parent in this story, she’d never heard of fake pills till one of them killed her son. And the notion that Snapchat might be a hub for bad actors? It never once crossed her mind. “First off, I couldn’t make heads or tails of [Snap],” she says. “It’s like it was made to be inscrutable to adults.”

She’s not wrong, says Marquez-Garrett. If you downloaded the app and self-identified as a grownup, you’d get a whole lot of nothing in your feed. Some innocuous friend suggestions; pushy requests to link your Contacts; and a spinning wheel of crass but harmless fluff. But log in as a teen and you’d find a vastly different bag. “Based on our interviews with a hundred-plus kids, boys were getting menus for serious drugs within weeks of signing up. If you were a girl, you were getting dick pics from strangers — even if you posted no content of your own,” says Marquez-Garrett.

Snap’s response: “Quick Add makes friend suggestions based on a mutual connection. Quick Add does not recommend users based on shared interests or because users may be near a similar location like a school or a park. Approximately 90 percent of friend requests received by teens on Snapchat are from someone with at least one mutual friend in common. And even for the remaining percent, the Snapchat user would need to affirmatively accept the friend request before someone can communicate with them.”

Marquez-Garrett is a former partner at a prestige practice who left their corner office to join the Social Media Victims Law Center in Seattle. It’s a newish firm of five attorneys who banded together for one goal: to hold Snapchat and its rivals — Meta, TikTok, and Google (owner of YouTube) — accountable for the harms they’ve done to children. Three years ago, that mission was a moon shot: to come up against four platforms that were protected by settled law and whose collective worth was in the trillions. Other lawyers thought “this was righteous but Sisyphean,” says Matthew Bergman, the firm’s founder. “Everyone suing these companies lost, and most didn’t get past dismissal motions.”

Amy Neville, mother of Alex

Photograph by Todd Cole

But Bergman’s the sort of lawyer who strikes fear in fat cats’ hearts. For more than 20 years, he beat asbestos makers in court, sending manufacturers into bankruptcy after they paid out billions of dollars to their victims. “In what other industry can you harm your young users and keep doing business like it never happened?” he asks. “They’ve used the same legal fig leaf” — Section 230 — “as a license to damage children.”

Section 230 treated web firms of the Netscape era as next-gen telecom companies. It viewed their platforms as services, not products, a crucial distinction for liability. “If you hired me over the phone to kill your wife,” says Bodner, “Sprint couldn’t be charged as an accomplice.” But what lawmaker of the 1990s could have foreseen a time when 12-year-olds had the internet in their pocket?

“The first claim we filed [against Snapchat, Meta, and TikTok] was on behalf of Selena, a young girl who killed herself on livestream,” says Bergman. “She was offered money by older men to masturbate on camera — starting at the age of 10.” Lonely and addicted to her social media feeds, Selena plunged into a deep despond and filmed her death-by-overdose on Snap. She was 11 years old.

Bergman now represents more than a thousand families who say their kids were exploited on social media. Most of his cases share a baseline claim: that social media firms have crafted their platforms’ features to addict young brains for profit.

Bergman’s contention is that fentanyl killed these children after Snap connected them to dealers. That’s why he broke out poisoning deaths, presented them as a separate group of civil claims — and named only Snapchat as the offender. In the spring of 2023, he filed 64 claims against Snap in an L.A. courthouse, seeking unspecified damages on behalf of Alex Neville and dozens of other children who died. He has dozens more families waiting in line, queueing for their chance to hold Snapchat accountable in the deaths of their sons and daughters.

“Our position is that Snap’s features gave dealers a safe haven to sell kids lethal drugs,” says Bergman. “The geo-locator feature; the My Eyes Only feature, which let them store and hide kids’ info; and Snap’s back-end deletion of dealers’ texts and menus. Those features are unique to Snap.” Additionally, he’s suing Snap for negligence, alleging that Spiegel and his colleagues knew for years that kids were meeting dealers on Snap — and that the company did little to fix the problem.

We won’t be bought out. All I care about is to see what Snap knew and when they knew it. —Alex’s mom, Amy Neville

Snap disputes those charges: “We have been working for years to remove dealers from our platform. We proactively detect and remove drug-related content. Our Trust and Safety team has grown more than 150 percent since 2020, and our Law Enforcement Operations team has grown about 80 percent.” Snap also sent me links to the company’s transparency reports: twice-a-year breakouts of “violative content” that Snap flagged and/or removed. In 2023, Snap reported that it “removed more than 2.2 million pieces of drug-related content, and disabled and blocked devices associated with 705,000 related accounts.”

But since Snap is encrypted from end to end, I asked their reps to ratify those stats. They sent me to Tim Mackey, a renowned data scientist whose company, S-3, scours the internet for dealers. Snap retained him in 2022, but, he says, it never brought him behind the curtain to scan its data for drugs. Instead, they hired him to scrape other platforms and “report those users back to Snap.” What Snap does with that information “isn’t reported to us, though we’re told they take down accounts,” he adds. “But that’s probably a small percentage of Snapchat dealers — and there’s no way of knowing even that much.”

He did say he’d seen “a reduction of dealers” flashing Snap handles on other sites, and praised Snap for staffing up its security team, saying its ratio of monitors was now higher than the industry average. But whether those fixes have stemmed the flow of drugs is another matter entirely. “I’m pessimistic,” he says. “There’s still an upsurge of dealing on platforms where you’d least expect it.” Asked what it would take to improve kids’ safety on socials, Mackey didn’t pause before he spoke. “The criminal indictment of a tech firm,” he said, “such as the investigation against Meta, to communicate the seriousness of the issue and ensure platforms are accountable to users and their families.”

‘It’s hell to make these cases’

As a rule, poisoning cases are uphill battles: The evidence is ephemeral, then disappears. “Ninety-five percent of the cases go unsolved,” says Bodner, whose office invested a year, and 500-plus man-hours, in the Alex Neville case. Dave Mertus, one of Bodner’s most reliable agents, ran into the usual headwinds. It took his experts months to open Alex’s iPhone, by which time any texts between Alex and the dealer had long since turned to smoke. Sit-downs with his school friends produced no leads, and subpoenas to FedEx and the U.S. Post Office showed no parcels received from suspected dealers. The only hard data was the coroner’s report. That fake Oxy Alex swallowed contained enough fentanyl to kill all four members of his household.

Mertus, who’s retired now, declined to comment, but provided his case notes through a source. He ID’d AJ Smokxy as a 21-year-old male with gang ties to MS-13. Shortly thereafter, Smokxy was arrested by Orange County deputies. A search of his car and house yielded around 60 fake pills. But those deputies didn’t know that Smokxy was linked to Snapchat deaths — and besides, this was California, post-Prop 47; that ballot initiative, passed in 2014, slashed most drug offenses to misdemeanors. And so Smokxy was kicked loose on little or no bail, then pinched again three months later. This time, he spent three days in lockup before they freed him on time served. In all, he was nailed seven times in three years. His longest stint in jail was eight months.

But Mertus had his phone now and got a warrant to search it while he waited for Smokxy’s data from Snapchat. Here, according to the DEA, was where many of these cases died: waiting for data from Snap. Mertus subpoenaed Snap in March 2021. A month later, Snap rejected that motion for being “ambiguous;” it sought data on four Smokxy accounts, not just one. Weeks went by before Snap answered a second subpoena, sending Mertus useless information. “No phone number, no email, no log-in, or log-out dates — just some gibberish about an account holder named ‘Ronald,’” says Bodner.

Snap’s rejoinder: “We cannot discuss specific law-enforcement requests when they are covered by nondisclosure orders. But when law enforcement submits a subpoena we can respond by providing basic subscriber information and IP address logs.” Moreover, Snap claims that it has begun inviting feedback from law enforcement, with “more than 93 percent of respondents reporting they had a ‘good’ experience with the company. When law enforcement provides a search warrant we can respond with content data preserved or available in the account if the warrant contains a valid request for it.”

Per Bodner, though, a subpoena was the correct court order in this case; the DEA wasn’t looking for content from Snap, just contact information. Mertus knew who Smokxy was — his name certainly wasn’t Ronald — he just didn’t have enough to nail him. “The prosecutors here refuse to indict unless it’s trafficking weight — at least 4,000 pills for fentanyl,” says Bodner. “So these dealers get out a half-dozen times, even if they’re dead to rights.”

Bodner, who took retirement last fall, had more luck than most in making cases. His office won 20 convictions in five years against fenta-pill dealers in SoCal. Rather than truck with local DAs, he ordered his agents to build federal cases and bring them to U.S. Attorneys. “There’s a statute we can use [in federal court] if we can prove that that dealer sold that pill,” he says. It’s called “death-resulting, or great bodily harm,” and carries 20 years of fed time upon conviction. Still, it’s hell to make those cases, per Bodner. “In all my years of doing this, we got nothing back from Snap, so we had to get lucky with the [victim’s] phone.” They needed to open it within hours, before those texts disappeared, or hope that child and dealer spoke by other means — a phone call, or non-Snap texts.

Meanwhile, Amy Neville sat and seethed as Alex’s case turned cold. But given her gifts as a connector, it was just a matter of time before she met a mom with whom she shared a poisoner. Perla Mendoza, an educator and makeup artist, lost her son three months after Alex died. Daniel “Elijah” Figueroa, 20, was a soulful church kid on the prongs of a spiritual crisis. He loved Jesus and he loved Juice WRLD, generally in that order. He filled notebook after notebook with mumblecore raps about girls and God’s forgiveness; detested narcotics but got hooked on Xanax after being treated for a mood disorder; and morphed from star student to mopey shut-in, doomscrolling Snap till 3 a.m.

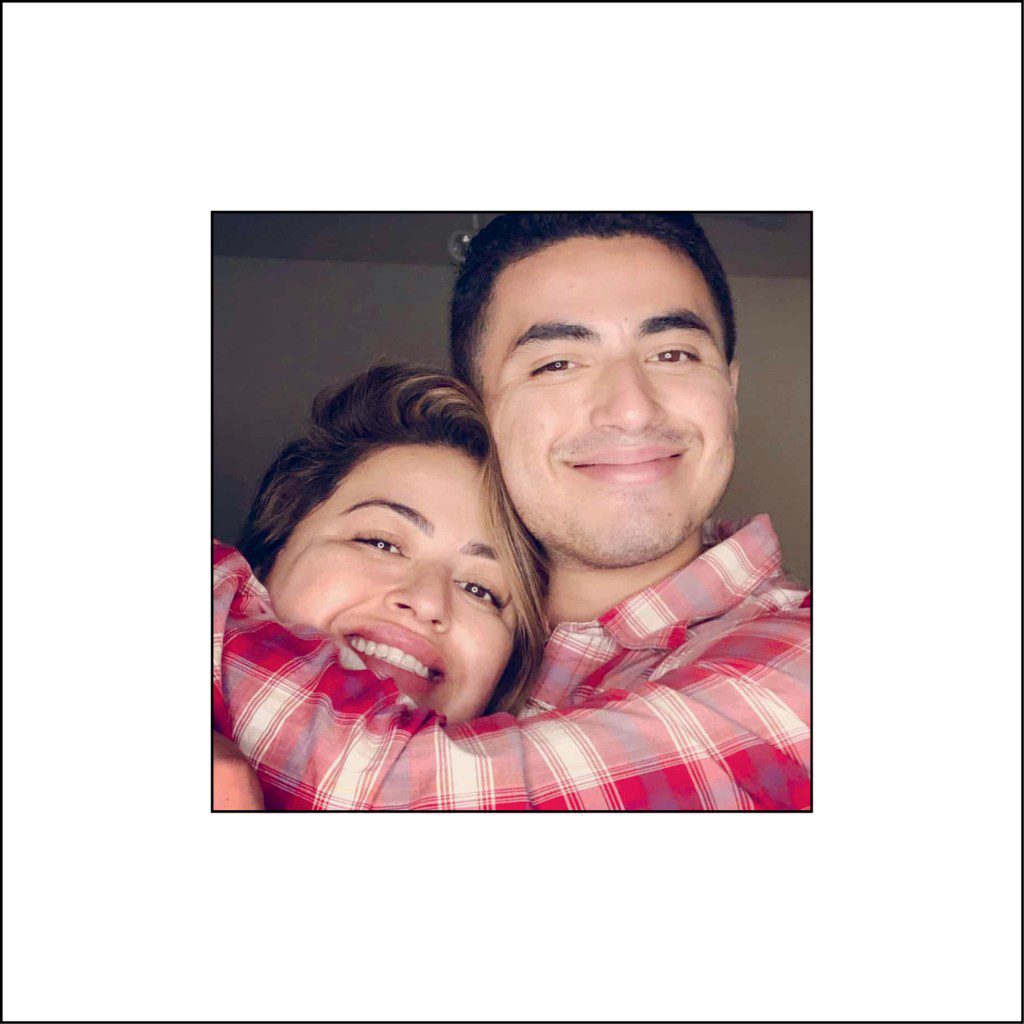

DANIEL “ELIJAH” FIGUEROA

With his mom, Perla; after he OD’d at age 20, she tracked down the dealer who sold him fake pills.

One night, he wrote his mom a sunny text: “Let’s get coffee [tomorrow] and read our bibles!” Hours later, his grandma found him hunched over his bed. He was fixed in a prayer position, dead. On his phone were saved messages from a Snapchat dealer calling himself Arnoldo_8286. He’d sold Elijah 15 “percs” via Snap the previous day. All 15 bore fatal doses of fentanyl.

A Long Beach, California, detective, Marc Cisneros, sent a search warrant to Snap two weeks after Eli died. Snap received it on Oct. 8, 2020, but didn’t respond to its merits till February of the following year, when it told Cisneros his warrant was “deficient.” Cisneros sent Snap a corrected warrant. Finally, Snap sent him “comms logs and data” pertaining to Arnold’s account — six months after he filed his first warrant. Whatever was in those logs didn’t avail the detective: His effort to charge Arnold in the death of Elijah was declined by the DA, who didn’t respond to my requests for comment.

Meanwhile, Mendoza says she reached out to Snap through the help-center widget on the app. She begged them to cooperate with Cisneros; Snap sent her back a link titled “how to use memories.” She wrote Snap again, beseeching them to close Arnold’s account “before he kills more people.” Snap thanked her for the report and suggested she block him. This went on for months, says Mendoza; she took it upon herself to drive to Snap’s office and file a report in person. But she was never allowed upstairs by Snap’s security, she says. Instead, they threatened to tow her car if she didn’t leave the premises immediately.

Asked about their handling of Mendoza’s pleas, Snap says: “Our heart goes out to Ms. Mendoza for the unimaginable pain she and her family have experienced. Unfortunately Ms. Mendoza did not contact Snap through a support channel, but rather replied to a seasonal or promotional message from Snap; this would likely be why the next message from that source may have been a different seasonal or promotional message.”

Unable to sleep or eat, Mendoza tailed Arnold online. She’d created a fake account, befriended him on Snap — then reported his every movement to the cops. There he is at a SoCal inn, posting a livestream reel of his “drugstore” wares: “Got bars … got oxy …got fuckin’ addys. C’mon, bro: Come shop!” That account stayed up until April 2021, when a reporter from Business Insider called out Snap’s inaction. At last, Snapchat pulled down Arnold’s account — but he promptly opened a new one and went on dealing, according to screenshots provided by Mendoza.

One day, Mendoza saw a post on Arnold’s feed; he was on his way to buy himself a car. She raced to the dealership with her spouse, intent on confronting her son’s poisoner. Barging into CarMax, she saw him at a sales desk, filling out the paperwork for his purchase. “I suddenly got sick, like I was gonna faint or throw up,” she says. She stumbled out to summon the police. But Arnold soon came strutting out. His boys were idling in a Chevy Yukon; they hooted out the window when he flashed the keys. Arnold got into his new blue Mazda. Mendoza slumped in the seat of her car, watching as he rounded the corner.

How many boys and girls must die in their beds before a movement rears its head? For Neville, the answer was: no more. She’d launched a foundation in Alex’s name, appeared at public functions to warn school kids and parents, and lobbied politicians for a suite of new laws to protect young users of social media.

But busywork’s no substitute for a public burning. On the morning of June 4, 2021, she brought a hundred parents to a park in Santa Monica; carrying signs and banners, they marched on their enemy: Snapchat. For hours, they stood at Snap’s corporate doorstep and shouted in the direction of Evan Spiegel. “We got on the bullhorn and called him what he is: a coward,” says Jaime Puerta, a small-business owner in Santa Clarita who lost his son Danny in 2020. “Just seeing [that] fucking logo brought the pain back double. But for the first time since our kids died, we broke through, man.”

Suddenly, those parents were media go-to’s on all the morning talk shows. They also succeeded in piercing the veil; Amy Neville got a phone call three days later. “Snap reached out to me,” says Neville. “They wanted to know the [Snapchat] handle of my son’s killer.” This struck Neville as deeply strange — and enraged her even all the more. “As if I would ever help them,” she says. For months, she says, she’d been told that Snap had gone mute while Smokxy went on dealing to Snap’s users. Nonetheless, the feds had a bead on Smokxy, and were about to drop the hammer. They were days from doing a buy-and-bust that would send him down for years, so long as nothing — and no one — spooked him.

But months passed by with no word. Neville wrote a letter to Anne Milgram, the chief of the DEA. She’d lost patience with the agent working her son’s case “after two years of little or no progress.” As a courtesy to Bodner, though, she sent it to him first. He called the next day with hard news. “I told her that, sadly, Alex was now a cold case,” says Bodner. “We’d had our crack at Smokxy, but — something happened.”

What happened was this: On the morning of June 7, 2021 — five days before the planned buy-and-bust from AJ Smokxy, and three days after the parents’ rally outside Snap’s office — the feds opened Snapchat and found his account … gone. His profile, his posts, his menus: Every last trace of him was wiped.

“What the hell?” said Neville, gobsmacked, after Bodner told her. Bodner couldn’t explain it — and he remains furious three years later. “We’d been on Smokxy for a year, and then, a day or two before we nail him, he goes poof?”

I asked Snap to explain what became of Smokxy’s account. The company says it deleted it on June 5, when its “proactive detection tools” flagged him for “drug-related activity.” “Proactive?” I said. Smokxy had been selling fentanyl for years on Snap, and was implicated in three deaths.

For now, there’s no way to know why that account suddenly vanished. But that’s what a courtroom trial is for: to determine baseline truths and responsibility. Sometime next year, Neville’s landmark case will begin, barring either a dismissal or a settlement. “We won’t be bought out,” says Neville, flatly. “All I care about — all any of us care about — is to see what Snap knew and when they knew it. Just getting it out in public will be all the compensation I ever need.”

Until then, she lives with two hard-hearted facts. AJ Smokxy is still out there, in vanish mode, after serving a gun rap in 2022. And Alexander Neville, forever 14, would have walked across a stage with his friends in June, having graduated from Dana Hills High School. With his hunger for minutiae and a mind that never stopped, he might have moved on to a place like Stanford, where the boys with big ideas and sleepless brains go to rescue or ransack the future.

If you are concerned about a child’s substance use and need support, education, and resources, please visit the nonprofit organization Hopestream Community at hopestreamcommunity.org. Or contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

The online edition of this story was updated from the print version to more accurately reflect information sought by the DEA in the AJ Smokxy case.