Fake Photos, Real Harm: AOC and the Fight Against AI Porn

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was in a car talking with her staffers about legislation and casually scrolling through her X mentions when she saw the photo. It was the end of February, and after spending most of the week in D.C., she was looking forward to flying down to Orlando to see her mom after a work event. But everything left her mind once she saw the picture: a digitally altered image of someone forcing her to put her mouth on their genitals. Adrenaline coursed through her, and her first thought was “I need to get this off my screen.” She closed out of it, shaken.

“There’s a shock to seeing images of yourself that someone could think are real,” the congresswoman tells me. It’s a few days after she saw the disturbing deepfake, and we’re waiting for our food in a corner booth of a retro-style diner in Queens, New York, near her neighborhood. She’s friendly and animated throughout our conversation, maintaining eye contact and passionately responding to my questions. When she tells me this story, though, she slows down, takes more pauses and plays with the delicate rings on her right hand. “As a survivor of physical sexual assault, it adds a level of dysregulation,” she says. “It resurfaces trauma, while I’m trying to — in the middle of a fucking meeting.”

The violent picture stayed in Ocasio-Cortez’s head all day.

“There are certain images that don’t leave a person, they can’t leave a person,” she says. “It’s not a question of mental strength or fortitude — this is about neuroscience and our biology.” She tells me about scientific reports she’s read about how it’s difficult for our brains to separate visceral images on a phone from reality, even if we know they are fake. “It’s not as imaginary as people want to make it seem. It has real, real effects not just on the people that are victimized by it, but on the people who see it and consume it.”

“And once you’ve seen it, you’ve seen it,” Ocasio-Cortez says. “It parallels the same exact intention of physical rape and sexual assault, [which] is about power, domination, and humiliation. Deepfakes are absolutely a way of digitizing violent humiliation against other people.”

She hadn’t publicly announced it yet, but she tells me about a new piece of legislation she’s working on to end nonconsensual, sexually explicit deepfakes. Throughout our lunch, she keeps coming back to it — something real and concrete she could do so this doesn’t happen to anyone else.

Deepfake porn is just one way artificial intelligence makes abuse easier, and the technology is getting better every day. From the moment AOC won her primary in 2018, she’s dealt with fake and manipulated images, whether through the use of Photoshop or generative AI. There are photos out there of her wearing swastikas; there are videos in which her voice has been cloned to say things she didn’t say. Someone created an image of a fake tweet to make it look like Ocasio-Cortez was complaining that all of her shoes had been stolen during the Jan. 6 insurrection. For months, people asked her about her lost shoes. These examples are in addition to countless fake nudes or sexually explicit images of her that can be found online, particularly on X.

Ocasio-Cortez is one of the most visible politicians in the country right now — and she’s a young Latina woman up for reelection in 2024, which means she’s on the front lines of a disturbing, unpredictable era of being a public figure. An overwhelming 96 percent of deepfake videos are nonconsensual porn, all of which feature women, according to a recent study by the cybersecurity company DeepTrace Labs. And women who face multiple forms of discrimination, including women of color, LGBTQ+ people, and women with disabilities, are at heightened risk to experience technology-facilitated gender-based violence, says a report from U.N. Women.

In 2023, more deepfake abuse videos were shared than in every other year in history combined, according to an analysis by independent researcher Genevieve Oh. What used to take skillful, tech-savvy experts hours to Photoshop can now be whipped up at a moment’s notice with the help of an app. Some deepfake websites even offer tutorials on how to create AI pornography.

What happens if we don’t get this under control? It will further blur the lines between what’s real and what’s not — as politics become more and more polarized. What will happen when voters can’t separate truth from lies? And what are the stakes? As we get closer to the presidential election, democracy itself could be at risk. And, as Ocasio-Cortez points out in our conversation, it’s about much more than imaginary images.

“It’s so important to me that people understand that this is not just a form of interpersonal violence, it’s not just about the harm that’s done to the victim,” she says about nonconsensual deepfake porn. She puts down her spoon and leans forward. “Because this technology threatens to do it at scale — this is about class subjugation. It’s a subjugation of entire people. And then when you do intersect that with abortion, when you do intersect that with debates over bodily autonomy, when you are able to actively subjugate all women in society on a scale of millions, at once digitally, it’s a direct connection [with] taking their rights away.”

She’s at her most energized in these moments of our conversation, when she’s emphasizing how pervasive this problem is going to be, for so many people. She doesn’t sound like a rehearsed politician spouting out sound bites. She sounds genuinely concerned — distressed, even — about how this technology will impact humanity.

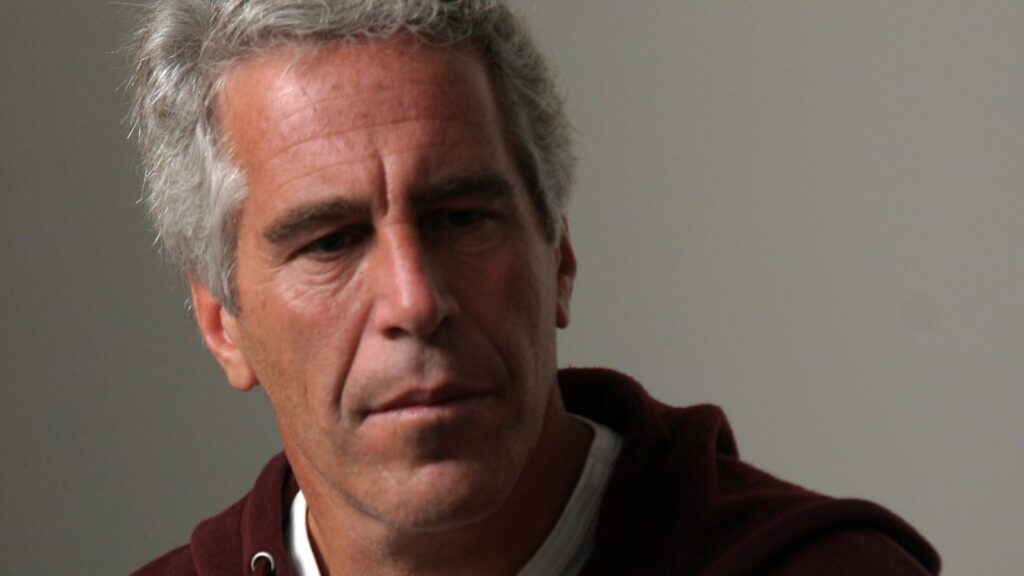

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is co-leading the effort to stop AI abuse with the DEFIANCE Act of 2024.

Kent Nishimura/”Los Angeles Times”/Getty Images

Ocasio-Cortez is living through this nightmare as she fights it. She’s watched her body, her voice, everything about herself distorted into a horror-film version of reality. It’s deeply personal, but if she can figure out the antidote to help end this shape-shifting form of abuse, it could change how the rest of us experience the world.

BACK IN THE early 2010s, before generative AI was widespread, abuse experts rang warning bells about altered images being used to intimidate communities online. Nighat Dad is a human-rights lawyer in Pakistan who runs a helpline for survivors being blackmailed using images, both real and manipulated. The consequences there are dire — Dad says some instances have resulted in honor killings by family members and suicide.

“This process has been going on for a while, and women of color, feminists from the Global South have been raising this issue for so long and nobody paid any attention,” Dad says.

Here in the U.S., Rep. Yvette Clarke (D-N.Y.) has tried for years to get Congress to act. In 2017, she began to notice how often Black women were harassed on social media, whether they were the targets of racist remarks or offensive, manipulated images. On the internet, bigotry is often more overt, where trolls feel safe hiding behind their screens.

“That’s what really triggered me in terms of a deeper dive into how technology can be utilized overall to disrupt, interfere, and harm vulnerable populations in particular,” Clarke says.

At the time, the technology around deepfakes was still emerging, and she wanted to establish guardrails and get ahead of the harms, before they became prevalent.

“It was an uphill battle,” Clarke says, noting that there weren’t many people in Congress who had even heard of this technology, let alone were thinking of regulating it. Alongside Clarke, Sen. Ben Sasse (R-Neb.) was an exception; he introduced a bill in December 2018, but it was short-lived. On the House side, the first congressional hearing on deepfakes and disinformation was in June 2019, timed with Clarke’s bill, the DeepFakes Accountability Act. The legislation was an attempt to establish criminal penalties and provide legal recourse to deepfake victims. She reintroduced it in September 2023.

In May 2023, Rep. Joe Morelle (D-N.Y.) introduced the Preventing Deepfakes of Intimate Images Act, which would have criminalized the sharing of nonconsensual and sexually explicit deepfakes. Like previous deepfake legislation, it didn’t pick up steam. Clarke says she thinks it’s taken a while for Congress to understand just how serious and pervasive of an issue this is.

Now, finally, people are starting to pay attention to the dangers of all types of AI abuse. Clarke is vice chair of the Congressional Black Caucus, which just announced the launch of an AI policy series that will look at this kind of technology through the lens of race. The series will address algorithmic bias in AI systems and will educate the public on misinformation, particularly in regard to disinformation campaigns against Black voters. And Clarke is a part of the House’s new bipartisan task force on AI, alongside Ocasio-Cortez and 22 other members, plus the two leaders of the House.

“Thank God, folks have finally recognized that civil rights are being violated,” Clarke says. “The work that we do now has implications not just for this generation, and not just for now, but for future generations. And that’s why it’s important that we act swiftly.”

As the technology has advanced rapidly, so has the abuse. And as Clarke points out, the harm is no longer just focused on marginalized communities. It’s become widespread, affecting teens and college students across the country. It can happen to anyone with a photograph online.

In May 2020, Taylor (who asked to use an alias to avoid further abuse) had just graduated college and was quarantining with her boyfriend in New England when she received an odd email, with the subject line: “Fake account in your name.” A former classmate of hers had written the email, which started out, “Look, this is a really weird email to write, but I thought you would want to know.”

The classmate went on to tell Taylor he’d seen a fake Pornhub account of hers with her name and personal information on it. “It looks like they used a deepfake to put your face on top of some videos,” he wrote.

Confused, Taylor decided it must be spam. She sent the classmate a message on Facebook saying, “Hey, I just want to let you know your account got hacked.” No, he replied, it had been a genuine email.

Four years later, she recalls that she hadn’t even known what a deepfake was at the time. She opened her boyfriend’s computer and went to the Pornhub link her classmate messaged her. When the website loaded, she saw her face staring back at her in a sexually explicit video she’d never made.

“It was surreal seeing my face … especially the eyes,” she tells me during a zoom call. “They looked kind of dead inside … like the deepfake looked realistic but it doesn’t quite look like — it looks like me if I was spacing out.”

She noticed the account had multiple videos posted on it, with photos taken from her Facebook and Instagram pages. And the videos already had thousands of views. She read the comments and realized some people thought the videos were real. Even scarier, the Pornhub profile had all of her very real personal information listed: her full name, her hometown, her school. (A spokesperson for Pornhub says nonconsensual deepfakes are banned from the site and that it has teams that review and remove the content once they are made aware of it.)

Taylor started diving deeper online and realized multiple fake accounts with videos had been made in her name, on various sites.

Suddenly, Taylor realized why she’d seen an uptick in messages on all of her social media accounts the past few weeks. She immediately felt very concerned about her physical safety.

“I had no idea if the person who did it was near me location-wise, [or] if they were going to do anything else to me,” Taylor says. “I had no idea if anyone who saw that video was going to try to find me. I was very physically vulnerable at that point.”

She and her boyfriend called the local police, who didn’t provide much assistance. Taylor played phone tag with a detective who told her, “I really have to examine these profiles,” which creeped her out. Eventually, she says, he told her that this was technically legal, and whoever did it had a right to.

It was the first few months of Covid, and Taylor, who lives with anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder, says she’d already been facing a general sense of worry and paranoia, but this exacerbated everything. She got nervous when going out that a stranger would recognize her from the videos. She fixated on who in her life had seen them. On the verge of starting graduate school, she wondered if future employers would find them and if her career would be over before it had even started.

In the months that followed, Taylor discovered that a girl she knew from school had also had this happen to her. Through their conversations, they were able to pinpoint a guy they’d both had a falling out with — a guy who happened to be very tech-savvy. As they continued to investigate, they came across multiple women from their college who’d been similarly targeted, all connected to this man they call Mike. But the state police were never able to prove he made the videos.

Taylor was one of the first to speak out about her AI abuse, anonymously sharing her story in the 2023 documentary Another Body. The filmmakers have started an organization called #MyImageMyChoice to tackle intimate image abuse. In March, the organizers co-hosted a virtual summit on deepfake abuse, with legal experts, advocates, and survivors like actor Sophia Bush telling their stories.

Taylor says that in the aftermath of that deepfake, she often feels out of control of her own life. She compensates for it by trying to be in control of other situations. She repeatedly beeps her car to make sure that it’s locked, and is often terrified the coffee pot is still on and her house is going to catch on fire. “I still deal with it today,” she says of her heightened OCD.

Mike was interested in neural networks and machine learning, Taylor says, which is how she suspects he could have created the deepfake before there were easily accessible apps that did this instantaneously like there are now. According to #MyImageMyChoice, there are more than 290 deepfake porn apps (also known as nudify apps), 80 percent of which have launched in the past year. Google Search drives 68 percent of traffic to the sites.

One of the people Taylor’s been connected to in the online abuse-advocacy space is Adam Dodge, the founder of the digital-safety education organization EndTAB (Ending Tech-Enabled Abuse). Dodge tells me people often underlook the extreme helplessness and disempowerment that comes with this form of tech-enabled trauma, because the abuse can feel inescapable.

For example, in revenge porn, when someone’s intimate images are leaked by a partner, survivors often try to assert control by promising to never take pictures like that again. With a deepfake, there is no way to prevent it from happening because somebody can manifest that abuse whenever and wherever they want, at scale.

Dodge wants to reframe the conversation; instead of highlighting the phenomenon of new technology being able to create these hyperrealistic images, he wants to shift the focus to how this is creating an unprecedented amount of sexual-violence victims. He thinks that the more people are educated about this as a form of abuse, versus as a harmless joke, the more it could help with prevention.

He brings up a recent New Jersey school incident where someone made AI-generated nudes of female classmates. “The fact they were able to spin up these images so quickly on their phones with little to no tech expertise and engage in sexual violence and abuse at scale in their school is really worrisome.”

RUMMAN CHOWDHURY IS no stranger to the horrors of online harassment; she was once the head of ethical AI at X, back when it was called Twitter and before Elon Musk decimated her department. She knows firsthand how difficult it is to control harassment campaigns, and also how marginalized groups are often disproportionately targeted on these platforms. She recently co-published a paper for UNESCO with research assistant Dhanya Lakshmi on ways generative AI will exacerbate what is referred to in the industry as technology-facilitated gender-based violence.

“In the paper, we actually demonstrate code-based examples of how easy it is for someone to not just create harassing images, but plan, schedule, and coordinate an entire harassment campaign,” says Chowdhury, who currently works at the State Department, serving as the U.S. Science Envoy for AI, connecting policymakers, community organizers, and industry with the goal of developing responsible AI.

Chowdhury rattles off ways people can use technology to help them make at-scale harassment campaigns. They can ask generative AI to not only write negative messages, but also to translate them into different languages, dialects, or slang. They can use this information to create fake personas, so one person can target a politician and say that she’s unqualified or ugly, but make it look like 10 people are saying it. They can use text-to-image models to alter pictures, which Chowdhury and Lakshmi did for their research, asking a program to dress one woman up like a jihadi soldier and changing another woman’s shirt to say Blue Lives Matter. And they didn’t have to trick or hack the model to generate these images.

And it’s not just about generation, it’s about amplification, which happens even when people aren’t trying to be cruel. It’s something Chowdhury often saw while working at X — people retweeting a fake photo or video, not knowing it’s not real.

“People will inadvertently amplify misleading information all the time,” Chowdhury says. “It is a very big problem and also one of the hardest problems to address because the individual did not have malicious intent. They saw something that looked realistic.”

She says she thinks a lot of people have learned not to believe everything they read on the internet, but they don’t have the same mental guard against video and audio. We tend to believe those are true, because it used to be difficult to fake them. Chowdhury says she doesn’t know if we are all going to get better at identifying fake content, or if we will just stop trusting everything we see online.

“One of my big concerns is that we’re just going to enter this post-truth world where nothing you see online is trustworthy, because everything can be generated in a very, very realistic yet fake way,” Chowdhury tells me.

This is a human problem that needs a human solution. As Chowdhury points out, it’s not an easy problem to solve, but it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to. She offers up a multiprong approach. Social media companies can track individual accounts to see if they are coordinating with other people, or whether the same IP address has multiple accounts. They can adjust the algorithms that drive what people are seeing. People can mobilize their own communities by talking about media literacy. Legislators can work on protections and regulations, and find protections that don’t just put the onus on the survivor to take action. Generative-AI developers and the technology companies that platform them can be more transparent in their actions and more careful about what products they release to the public. (X didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

Mary Anne Franks, a legal scholar specializing in free speech and online harassment, says it’s entirely possible to craft legislation that prohibits harmful and false information without infringing on the First Amendment. “Parody and satire make clear that the information being presented is false — there is a clear line between mocking someone and pretending to be someone,” she says.

“And while the Supreme Court has held that some false speech may be protected,” she adds, “it has never held that there is a First Amendment right to intentionally engage in false speech that causes actual harm.”

Franks wants to see legislation on deepfake-AI porn include a criminal component as well as a civil component, because, she says, people are more often fearful of going to jail versus fearful of getting sued about something so abstract and misunderstood.

“While it is true that the U.S. is guilty of overcriminalizing many kinds of conduct, we have the opposite problem when it comes to abuses disproportionately targeted at women and girls,” Franks says, citing how domestic abuse, rape, and stalking are underprosecuted.

Online abuse disproportionately targets marginalized groups, but it also often affects women in public spaces, like journalists or politicians. Women at the intersection of these identities are particularly vulnerable.

Rep. Summer Lee (D-Pa.) says she often thinks about how rapidly this technology is advancing, especially given the unprecedented levels of harassment public figures face on social media platforms.

“There is just such a fear that so many of us have, that there will be no mechanisms to protect us,” Lee says. She says she already sees a world in which Black people and other marginalized folks are skeptical of the system following disinformation campaigns: “It makes voters and people who would otherwise run [for office] afraid that the system itself is untrustworthy. When I think about women who will run, especially Black and brown women, we have to think about the ways in which our images will be used and abused. That is a constant fear of women, and particularly women of color, who think about whether or not they want to put themselves out on a limb to run for Congress.

“You lose control of yourself to an extent when you are putting yourself out there to run for office, but in this era, it takes on a new meaning of what it means to lose control of your image, of your personhood. The ways in which this technology can exploit and abuse it, how it can spread, it can ruin not just reputations but lives.”

AT THE DELI, Ocasio-Cortez tells me something similar. We’re talking about how real the harm is for the victims of this kind of abuse. “Kids are going to kill themselves over this,” she says. “People are going to kill themselves over this.”

I ask Ocasio-Cortez what she would tell a teenage girl who has been victimized by AI abuse. “First of all, I think it’s important for her to know and what I want to tell her is that society has failed you,” she says. “Someone did this to you and it’s wrong, but society has failed you. People should not have the tools to do this.

“My main priority is making sure that she doesn’t internalize it, that the crime is not complete,” Ocasio-Cortez says. I ask her how she personally deals with it — is there something she does to avoid internalizing the abuse?

“I think of it not as an on switch or an off switch,” she says, adding that she often has young women asking her how it’s so easy for her to speak up. “It’s not,” she tells me. She slows down again, choosing her words carefully. “I think of it as a discipline, a practice. It’s like, ‘How good am I going to be at this today?’ Because some days I suck, some days I do internalize it, some days I don’t speak up because things have gotten to me.”

Ocasio-Cortez says that a lot of her politics are motivated by a sense of not wanting other people to experience the things that she or others have. “A lot of my work has to do with chain breaking, the cycle breaking, and this, to me, is a really, really, really important cycle to break,” she says.

We talk about Taylor Swift’s sexually explicit AI photos that went viral in January — she remembers being horrified when she heard about them. She’d already been working on the deepfake-AI legislation when it happened, but she says the Swift incident helped accelerate the timeline on the bipartisan, bicameral legislation. Sens. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) and Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) are leading the Senate version of the bill, while Ocasio-Cortez leads the House version. It’s called the Disrupt Explicit Forged Images and Non-Consensual Edits (DEFIANCE) Act of 2024. The legislation amends the Violence Against Women Act so that people can sue those who produce, distribute, or receive the deepfake pornography, if they “knew or recklessly disregarded” that the victim did not consent to those images.

The bill defines “digital forgeries” as images “created through the use of software, machine learning, artificial intelligence, or any other computer-generated or technological means to falsely appear to be authentic.” Any digital forgeries that depict the victims “in the nude or engaged in sexually explicit conduct or sexual scenarios” would qualify. If the bill passes the House and Senate, it would become the first federal law to protect victims of deepfakes.

The bill has support from both sides of the aisle, bringing together unlikely partners. For example, Rep. Nancy Mace (R-S.C.), who has publicly feuded with Ocasio-Cortez in the past, is a co-sponsor of the DEFIANCE Act.

“Congress is spearheading this much-needed initiative to address gaps in our legal framework against digital exploitation,” says a spokesperson for Mace, who recently introduced her own bill criminalizing deepfake porn. “Together, we are combating this chilling new wave of abuse against women and confronting the alarming rise in deepfake child pornography. We aim to bring perpetrators to justice and ensure the safety and security of all individuals in the digital realm.”

Durbin tells me he thinks the key to passing DEFIANCE into law is its significant bipartisan support.

“I really believe that politicians from both political parties and every political stripe are coming to the realization that this is a real danger,” he says, adding that having Ocasio-Cortez as a partner on the DEFIANCE Act is important.

“I’m saddened that she’s gone through this experience personally,” says Durbin. “But it certainly gives her credibility when she speaks to the issue.”

At lunch, I ask Ocasio-Cortez if she thought the fact that she was the youngest woman to serve in Congress — and a woman of color — has to do with why she’s a lightning rod for this type of harassment.

“Absolutely,” she says, without a moment’s hesitation. I ask her why she thinks people often target women in leadership roles.

“They want to teach us a lesson for being there, for existing: This is not your place, and because you’re here, we’re going to punish you,” she says.

We talk about fascinations people have with public figures, whether they’re artists, influencers, or politicians.

“People increasingly, since the emergence of smartphones, have relied on the internet as a proxy for human experience,” Ocasio-Cortez says. “And so if this becomes the primary medium through which people engage the world, at least in this country, then manipulating that becomes manipulating reality.”

The fight for reality can sometimes feel futile. Facing the AI frontier, it’s hard not to feel an undercurrent of dread. Are we entering a post-truth world where facts are elusive and society’s most marginalized are only further abused? Or is there still time to navigate toward a better, more equitable future?

“There have been times in the past where I did have moments where I’m like, ‘I don’t know if I can survive this,’ ” Ocasio-Cortez says quietly. “And in those moments sometimes I remember, ‘Yeah, that’s the point. That is quite literally the point.’ I was the youngest woman elected to Congress, and it took over 200 years for a woman in her twenties to get elected to Congress, when this country was founded by 25-year-old dudes! Do people think that’s a fucking coincidence?”

She’s back to being animated, and she seamlessly ties it back to her work: “It is by design, and even the AI represents — not AI in general, but this use of AI — the automation of that design. It’s the automation of a society where you can have an entire country be founded by 25-year-old men, but it takes over 200 years for a 29-year-old woman to get elected to Congress. And then once she is elected, they do everything in their power to get her to leave.”

She leans in and smiles.

“And guess what, motherfuckers? I’m not going anywhere. Deal with it.”