You Don’t Need to Record Video of Strangers in Public

It’s said that nobody likes a tattletale. So why does it seem as if many of us are eager to catch a random individual behaving suspiciously in public, record video of whatever they’re doing, and blow them up on the internet?

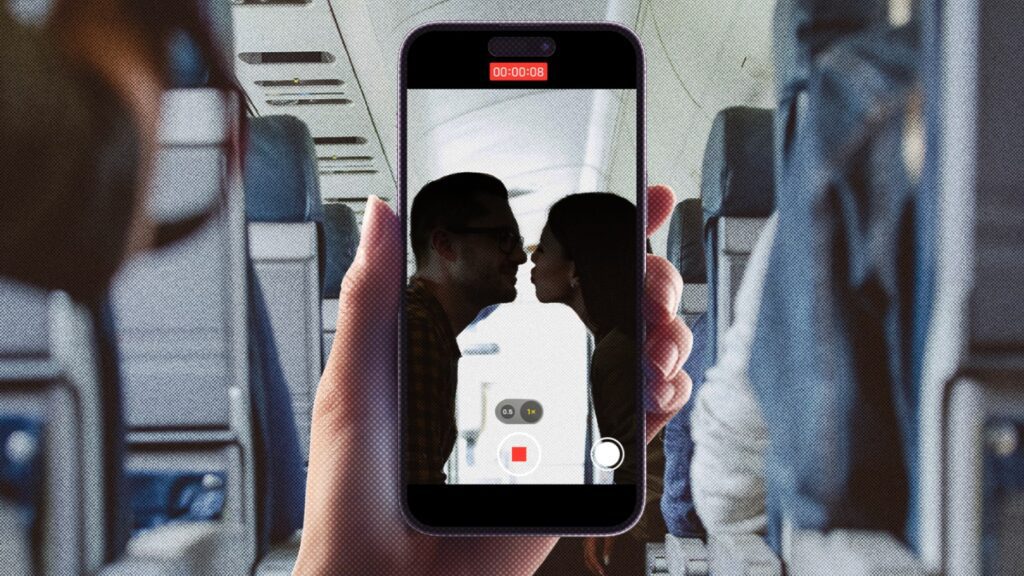

This week, TikTok was consumed with a domestic drama aboard an airplane, a cramped environment that reliably turns people into weird hall monitors as they log every conceivable breach of passenger etiquette. But this wasn’t about reclined seats, or someone clipping their toenails, or even someone refusing to move so a family could sit together. Instead, a TikTok user was surreptitiously documenting the cozy vibes between a man across the aisle and a woman he’d evidently met at the airport bar. The TikToker speculated, based on his wedding band, that the guy was cheating on his wife — and she wanted him exposed.

“If this man is your husband flying @United Airlines, flight 2140, from Houston to New York, he’s probably going to be staying with Katy tonight,” she wrote in the text on a since-deleted video, explaining that she’d seen the two meet and start drinking together before they boarded, and that they had arranged for the woman to change her seat to be next to him. She listed a number of identifying details she had overheard from the man, including where he lived and his daughter’s age, though she’d been unable to ascertain his name. She concluded the caption by encouraging a crowdsourced investigation: “Do your thing TikTok. #findthewife #cheatinghusbands.”

The masses obeyed, taking no time at all to produce his name, his wife’s name, and their Facebook pages, which it seems disappeared after both were barraged with messages from people who had seen the video. (Three days later, it had been played more than 30 million times.) Whatever emotional fallout attended this embarrassing virality is unknown, but it’s also categorically unimportant to those who derived entertainment from the scandal and efforts to out the mystery man. Those real lives would only get in the way of the fun.

One doesn’t need to defend marital infidelity, if that’s indeed what transpired, nor even PDA on a commercial flight. There’s something toxic, however, in operating as the self-appointed agent of a larger community surveillance apparatus that runs on smug righteousness. Tellingly, whenever a social media posse organizes to bust an accused wrongdoer and succeeds in tracking the target down, they congratulate themselves on being better detectives than the FBI. The media outlets that cheerily aggregate this stuff are no better, praising the amateur sleuths and echoing comments that hail vigilante videographers for doing “the Lord’s work.”

The precept which follows from this kind of thinking — that we ought to live as though our every public mistake may be virtuously amplified to a far greater audience for the purposes of ritualized shaming — is troubling and toxic. In a pre-smartphone era, such incidents would merely be the texture of day-to-day experience, perhaps a bit of idle gossip to share with a friend or partner after the fact. Now, of course, each is potential content: vicarious thrills for your followers, the dopamine rush of engagement for yourself.

While the discourse surrounding how phones have or haven’t altered our fundamental humanity is broad and ongoing (journalist Taylor Lorenz recently guest-hosted an episode of the podcast You’re Wrong About in which she argued, not without some blowback, that they aren’t really destroying the minds of younger generations), it’s clear that this is no way to live. You can’t terrorize a society into having morals and manners with the threat of online infamy. Meanwhile, we shouldn’t overlook the personal benefits of minding our own business, maintaining boundaries, and forgoing the impulse to treat whatever happens in earshot like a true crime saga.

A 2021 editorial from the New York Times summarized academic research on polarization in America with a headline that has since served as an invaluable meme: “We Should All Know Less About Each Other.” The idea, put forward by academics in the fields of sociology and communications, was that more exposure to politics we find disagreeable on platforms such as Facebook and Twitter make us more intolerant of whoever pushes them. There may be a parallel lesson to be taken from the intrusion complex that has us spying on strangers: delving into their petty failings, and turning them into entertainment, leaves spectators more cynical, assured that everyone walking around on this planet is a narcissist harboring foul little secrets.

There is nothing to be done regarding the voyeuristic nature of our species. We are noticers; we will always pick up on the unusual, the not-quite-right, and often enough we will start paying closer attention to it. Blasting out photos or footage of those we believe to be violating a code of conduct almost feels like a way to excuse and validate such nosiness: Isn’t this important? Shouldn’t we take action? Yet however one justifies it (by claiming to act in the interests of a betrayed spouse, for example), there’s no high ground to be had. You’re still the person dramatizing an unknown party’s misdeed to score those likes, replies, and shares. Drop the crusade — there are millions of moments when it’s better to be a bystander.