Twitter Let Terrorists Have Verification Checkmarks — Then Scrambled to Remove Them

Anyone active on X (formerly Twitter) since its acquisition by Elon Musk in late 2022 knows that hate speech, misinformation and extremism is rampant on the platform. At this point, such toxic content is simply the price of admission. But a new report from the Tech Transparency Project, a digital research nonprofit, reveals that terrorist leaders received paid verification badges and premium features on the site, possibly violating U.S. sanctions — as well as X’s own policies.

TTP’s report detailed how Hassan Nasrallah, secretary-general of the Lebanon-based Islamist political party and militant group Hezbollah (designated as a terrorist organization by the United States and other countries), enjoyed verified status on X starting in November 2023. Naim Qassem, Hezbollah’s second in command, gained a blue checkmark that same month. Other Hezbollah-linked individuals and outlets sharing the group’s propaganda — including a news feed called “Resistance Monitor” — had badges as well, indicating paid subscriptions to the site.

A blue check costs either $8 per month (for Premium features) or $16 monthly (for the Premium+ tier). Either type of subscription enables the user to edit posts, expand their character limit, and share longer videos. These users also have their replies pushed to the top of the feed — making them more visible across the site — and can apply to X’s revenue-sharing program, which pays creators for the engagement their content receives.

The presence of sanctioned groups like terrorist organizations on social media isn’t new, TTP director Katie Paul tells Rolling Stone. But Musk’s controversial decision to do away with traditional verification in favor of a paid service, she says, could put the company in the crosshairs of the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, the agency that enforces trade sanctions. (OFAC did not immediately return a request for comment.)

Prior to Musk, Paul says, “getting a verified checkmark was a free service. It wasn’t something that gave you any sort of algorithmic boost. It wasn’t paid. So there weren’t financial transactions taking place.” Now, though, it appears that X has received money from — and may have redistributed some of it to — entities it is forbidden to do business with. These range from Hezbollah and Yemeni Houthis militants to state-run media services and commercial enterprises including Iran‘s Press TV and Russia‘s Tinkoff Bank, both listed in OFAC’s database as Specially Designated Nationals that are subject to the U.S. sanctions against those two countries.

Paul notes that while the majority of the accounts mentioned in TTP’s report had blue badges, Press TV and Tinkoff Bank had the more expensive gold checks that denote a “Verified Organization.” (These initially cost $1,000 a month, but a “Basic” gold subscription with fewer features can now be had for $200 per month.) After these findings became public on Wednesday, X first went about removing the blue checks — then, a while later, the gold ones. At the time Press TV first reported that other Iranian state media outlets (two of which it directly owns) had lost their verified status, it still had a gold badge.

X responded to the report on the platform itself, claiming that some of the accounts listed may have had “visible account check marks” without receiving premium services. But this doesn’t make much sense, according to Michael Clauw, TPP’s director of communications. “The blue check alone is a service,” he tells Rolling Stone, as X’s policy states: “Premium: Includes all Basic features plus a checkmark.”

“If the accounts we cited were not in violation or not ‘receiving services,’ why did X remove their checkmarks?” Clauw asks. He’s also not swayed by X’s excuse about several of these groups or individuals not being explicitly named in OFAC’s sanctions database, because even if an entity is not listed there, it may be owned or controlled by one that is, and amplifying that actor’s harmful propaganda. “This is why companies have compliance efforts on these issues,” he says.

The issue is just the latest example of how Musk has opened up X to regulatory and financial risk by gutting most of its workforce — he estimated last year that he’d fired about 80 percent of employees within the first six months of his takeover. “We know that the platform and the company have laid off lots of trust and safety experts,” Paul says. The lack of moderation has led to a mass exodus of advertisers spooked by the likelihood of their brand name appearing next to hateful and extremist material — not to mention Musk’s penchant for far-right conspiracy theories.

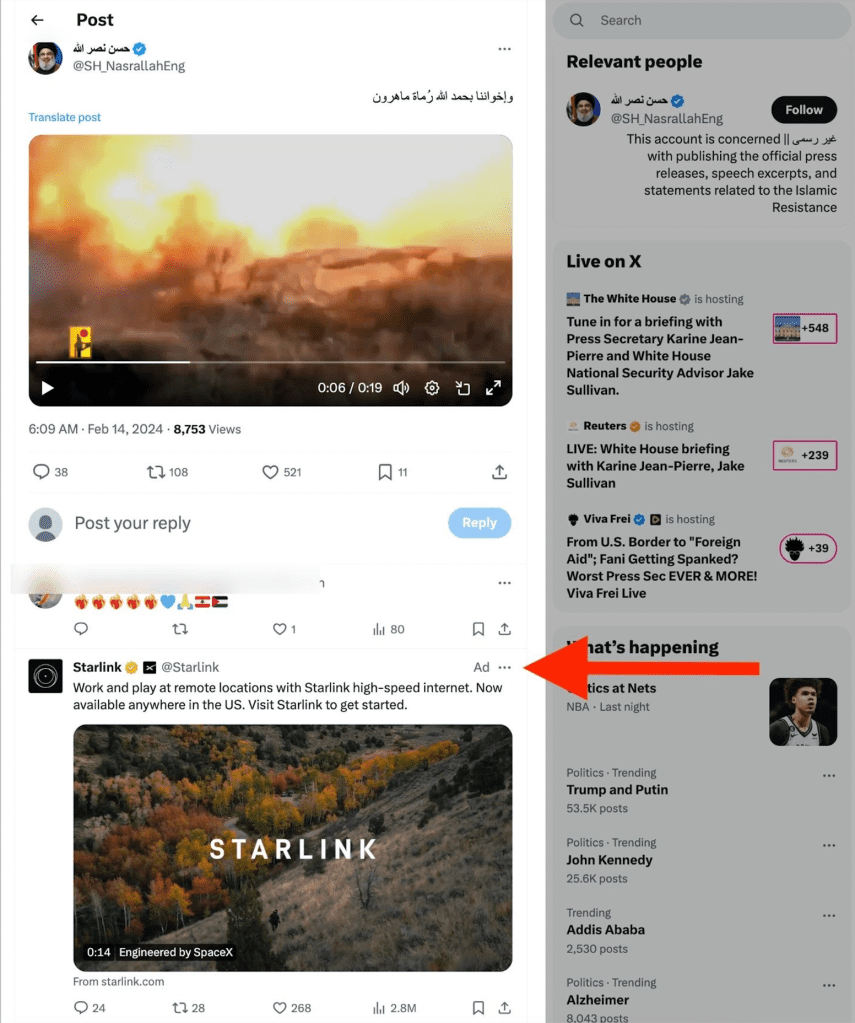

Ironically enough, the satellite internet service Starlink, operated by Musk’s SpaceX, on Wednesday had an ad served alongside a tweet from the still-verified account of Hezbollah leader Nasrallah, who was sharing a video that celebrated the group’s rocket attacks on Israel. TTP shared a screenshot of these posts with Rolling Stone. “Right now, Hassan Nasrallah is probably one of the most recognizable terrorist leaders in the world,” says Paul. “And in particular, it’s not just that he had the blue checkmark account, but that he also had the ID-verified badge,” for which X “requires a government ID and a selfie,” she says. “So does that mean that there’s a selfie of Hassan Nasrallah floating around somewhere at X? And, if not, does that suggest that the ‘ID-verified’ program is just a name? It doesn’t actually work?”

As of December, X is under investigation by the EU’s European Commission for aspects of its risk management and content moderation that may violate the union’s Digital Services Act. “Much of this content, independent of sanctions — the Hezbollah content, for instance — is a violation of the Digital Services Act,” Paul says. “There are some really strict provisions in there with regard to terrorism. But it’s also worth noting many of the entities sanctioned by the U.S. are also sanctioned by the EU. So the EU may have a different manner of pressure that they put on for sanctions violations.”

Beyond these bureaucratic headaches, Paul observes, X has failed to comply with its self-imposed rules. “They have their own policies that explicitly state sanctioned entities cannot use X’s premium services,” she says. “But they don’t appear to have any mechanism for enforcing that. And we’re not talking about free speech, we’re talking about violations of the Office of Foreign Assets Control, and the fact that this company is receiving, and, through revenue sharing, may even be providing funding to sanctioned entities and terrorist groups.”

Musk, for his part, tried to deflect blame with a random jab at transgender people. Responding to a tweet from Stephen King that referred to a New York Times article on the TTP report, the trollish billionaire scolded the author for continuing to call X “Twitter,” likening this to the offensive practice of “deadnaming.” Musk added, “Respect our transition,” along with a laugh-crying emoji.

It’s the sort of flaccid punchline that appeals to his fanboys, perhaps, but it’s unlikely to get X out of a hefty penalty or settlement payment should the company find itself held liable for the activities TTP described. Suddenly, the idea of charging people for a checkmark to cover the site’s expenses might not seem so brilliant.