They Practiced Their Instruments During Brain Surgery. Then They Played Nirvana Together

Robert Alvarez and Adrian Rivas both started playing their respective instruments — guitar and drums — at the age of 12. They shared a love of rock, especially the heavier kind, like grunge and metal. And, years later, each received the same devastating medical diagnosis: a brain tumor.

Rivas and Alvarez hadn’t met by the time they were individually considering treatment options. But their common experience would lead them to play music together under very special circumstances.

Alvarez was in high school when he began to suffer debilitating migraines, he tells Rolling Stone. “I remember my mother caught me going down the stairs, and I just had to sit,” he says, describing how he found himself in tears from the blinding pain. “That’s when we had to figure it out.”

After testing revealed his tumor in 2013, Alvarez became determined to fast-track his creative career while postponing any surgical procedure for fear of debilitating side effects, like problems speaking or walking. “I felt like I was wasting my time going to junior college and whatnot. And I just wanted to go try to hit it hard,” he says. So, at the age of 19 (he’s now 30), Alvarez moved from San Antonio to Chicago to work in audio engineering and started a metal band with a hardcore name inspired by his condition: Death From Within.

But Alvarez’s symptoms worsened, and one seizure put him in the hospital. It was then that his mother — who had been researching possible next steps all along — suggested he consult with the team at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. There, he met Dr. Sujit Prabhu, a neurological surgeon who specializes in brain tumor oncology. Prabhu determined that Alvarez’s case was suitable for a procedure known as an “awake craniotomy,” in which the patient is woken during surgery to ensure that particularly sensitive areas of the brain are not damaged, resulting in the loss of ordinary but vital functions.

“It’s kind of multifactorial,” Prabhu says, “but the main decision-making here is: If the tumor is located in what we call areas of brain function, primarily related to speech, or any type of cognitive function, as well as motor function — if we have tumors in these locations of the brain, we definitely discuss keeping patients awake.” Alvarez’s tumor, for instance, was close to some of these “eloquent” areas that directly control movement and speech.

“The brain itself has no sensation,” Prabhu says, meaning the operating team can continue to talk with the conscious patient to confirm that these important parts aren’t being affected. But Alvarez also wanted to preserve his guitar-playing abilities. Noting his passion for the instrument, Prabhu suggested he play during the operation so the medical staff could monitor his dexterity. It would be the first time they had a musician performing during a craniotomy. Of course, it had to be an acoustic set.

“I usually like playing Lamb of God, stuff like that,” Alvarez says, naming a favorite heavy metal band. For this occasion, however, he set about practicing different material — and was particularly inspired by a cover of Radiohead‘s “Creep” by a homeless musician named Daniel Mustard that went viral in 2009. Little did Alvarez suspect that his own “Creep” cover on the operating table would go viral when MD Anderson released the footage on YouTube following his 2018 surgery, drawing thousands of admiring and awestruck comments. “One friend told me, ‘You should have played “Zombie” by the Cranberries,” he says.

When the doctors woke him up during the procedure and asked about his state of mind, Alvarez says he told them, “I feel like a little fish right now” — the glare of the room perhaps suggesting a giant glass bowl. It was a surreal, somewhat overwhelming moment later matched by people’s emotional reaction to his story. “People were calling me, and a couple times I went to the store and people were like, you look so familiar, and I was like, was it the news, man? I’m a brain tumor survivor. I’ve had people hug me and cry. It’s crazy.”

The initial recovery period hampered his playing a bit — Alvarez was receiving chemotherapy and radiation treatment — and there were temporary problems with speech. Long-term, however, his outcome was enormously positive. “I recovered so well,” he says. “I feel so great on my feet right now. I’m just so excited.”

Four years after Alvarez’s operation, in the summer of 2022, drummer Adrian Rivas of Edinburg, Texas, found out about his own brain tumor following an MRI diagnosis to investigate the cause of a sudden seizure. “I had gone out for a run,” he said, and had originally assumed “it was just dehydration because it gets really, really hot down here.” Unfortunately, like Alvarez, he had astrocytoma, a type of cancerous growth that originates from nervous system cells in the brain or spine. And, as with Alvarez, Rivas’ mass was near a region responsible for motor function. Unsurprisingly, then, MD Anderson recommended the same kind of procedure.

Rivas, 36, “was extremely hesitant” to agree to the plan for an awake craniotomy, Prabhu recalls, saying this is not an uncommon stance for patients in his position. “Not many surgeries are performed awake,” he says. “So there’s not a lot of awareness of this type of procedure.” On top of a job that required the ability to type, Rivas worried about his drumming. This time, however, Prabhu had an ace up his sleeve: the video of Alvarez.

“Honestly, I was like, I don’t know if there’s any way I’d agree to this,” Rivas says of his thought process when first presented with the idea. “I didn’t even know that that was possible.” His nerves were allayed when he saw how “seamless” Alvarez’s operation looked, particularly as he was concerned by the “possibility that I might not be able to play drums again.”

Rivas agreed to play on his practice kit when woken up in order to test his movement as Prabhu removed the tumor. The surgeon says with a laugh that the drum kit was easier to manage than the guitar, which was more “logistically challenging” as the larger instrument, though as for musical stylings, it’s all the same to him: “I’m always in the zone when I operate, so I can have anything playing in the background and I’m just fine.”

“It was a pretty strange experience,” Rivas says, “because during the surgery, while I was playing, I could actually notice when he was cutting out the tumor. I would kind of lose feeling in my eyebrow. I couldn’t move, and then it would come back. It’s like I was being controlled like a robot.” He ran through some exercises with his sticks rather than playing the rhythm from any particular song — and the surgery was a success, with Rivas back to his ideal drumming speed after several months of physical therapy.

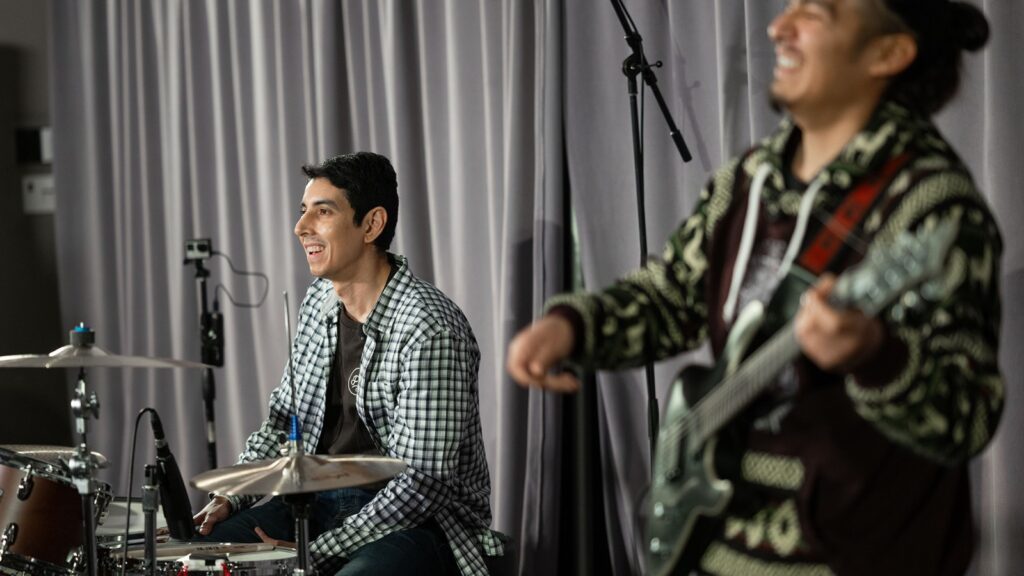

Rivas and Alvarez continue to receive regular checkups at MD Anderson, and in February, the two finally met there for the first time — to jam for the staff that provided their world-class care. They immediately bonded over their experience and favorite music, going over which songs might be doable in an impromptu concert.

“We only had, like, maybe 30 to 45 minutes to even practice,” Rivas says. “So we had to pick something that we could both play.” Alvarez had a “simple” song in mind — System of a Down‘s “Aerials,” but Nirvana was a better point of overlap. “He said his father introduced him to Nirvana,” Alvarez recalls of the conversation with Rivas. “So he likes that kind of grunge music. He’d also had a sludge [metal] band, he explained to me. I wasn’t too familiar with sludge.”

In the end, they performed a few tracks from Nirvana’s Nevermind, including “In Bloom,” to a crowd of delighted doctors and surgeons, many of whom played a role in the two men’s procedures. “They introduced themselves and said, ‘Hey, I did this part in your surgery, I’m glad to see you doing well,’ ” Rivas says. “And it’s just really cool. Because it wasn’t for them, I don’t know if I’d be able to play drums today.” Afterward, the event organizers gifted him a vinyl copy of Nevermind, while Alvarez received a System of a Down record.

In addition to connecting over their rock & roll tastes, Alvarez and Rivas talked about how their medical journey had brought them together. “When I met him, I felt, like, I did something good here at least,” Alvarez says, recounting how Rivas’ mother shook his hand and thanked him for helping to persuade her son to go ahead with the surgery. Before then, according to Alvarez, Rivas had taken the attitude that it might simply be his time. “It’s a different type of mindset you kind of enter at that point,” he explains.

“I asked him, ‘Man, how were you brave enough to agree to it, not ever seeing what the surgery was like?’ ” Rivas says, recounting to Alvarez how the guitar video had put him more at ease. “You didn’t know what to expect. And he said the alternative was basically to let the tumor keep growing, and he figured it was worth a shot.” He hopes their stories “can inspire somebody else to be courageous about this kind of surgery,” adding, “I would be happy if I could pay it forward.”

In Prabhu’s eyes, they already have. “Oh, my God, that was spectacular,” he says of their performance. “It was a very humbling experience to see to see them play together. I’ve said this before: They’re like my rock stars — with the passion they showed, the camaraderie and friendship.”

And while they live more than a thousand miles apart, Rivas and Alvarez are supporting one another’s musical ambitions from afar. Alvarez — now readying a debut album with Death From Within, which are set to play their first show in Chicago this month — says they’ll “definitely” keep in touch. Rivas, not currently in a band but practicing constantly in his home studio, says he and Alvarez have been sharing more music since their private concert. “We’re gonna be pretty good friends,” Rivas predicts. “He’s really cool.”