The Long, Discriminatory History of ‘Sex Verification’ at the Olympics

Two Olympic boxers have been the targets of unfounded personal attacks from the right, casting a dark shadow over a sporting event meant to foster peace and tolerance through athletic competition. Despite qualifying to participate in the boxing tournament at the Paris Olympic Games, Imane Khelif of Algeria and Lin Yu-ting of Taiwan have been attacked on social media by people who, based on the boxers’ physical appearance, claim that they are men or transgender women, and ineligible to compete in the women’s category.

The Paris 2024 Boxing Unit (PBU) and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) have repeatedly come to Khelif and Yu-ting’s defense, confirming that the women comply with the competition’s eligibility, entry, and medical regulations. “There was never any doubt about them being [women],” IOC President Thomas Bach said at a news conference on Aug. 3. “This is not a transgender case: This is about a woman taking part in a women’s competition.”

But that hasn’t stopped conservatives in the United States and Europe from decrying Khelif and Yu-ting’s participation in the Olympic boxing tournament, claiming that they have an unfair advantage over the other women competing in the event. As it turns out, this baseless outrage is the result not only of transphobic and misogynist bigotry, but a long history of discriminatory “sex verification” at the Olympics.

How the boxing controversy started

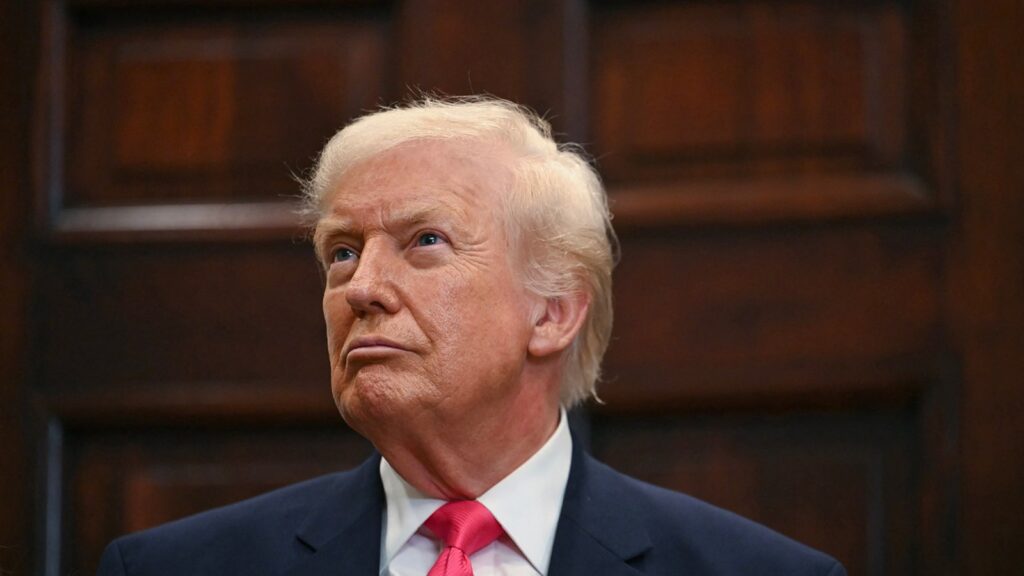

On Aug. 1, Khelif won her first bout in the Paris Olympics when her opponent, Angela Carini of Italy, quit after 46 seconds — prompting self-appointed arbiters of sportsmanship like Elon Musk, J.K. Rowling, J.D. Vance, and Fox News to respond with transphobic abuse and disinformation about the boxer, including claiming she’s a biological man or transgender woman. (She is neither.)

But these false claims didn’t materialize out of thin air; they first surfaced in March 2023, when both Khelif, 25, and Yu-ting, 28 — who have years of experience in top-tier international tournaments — were disqualified from the Russian-led International Boxing Association’s (IBA) World Championships for “failure to meet the eligibility criteria for participating in the women’s competition.”

So what, exactly, does that mean? At first, it was unclear. Last week, the IBA released a statement on the boxers’ 2023 disqualification, stating that they “did not meet the required necessary eligibility criteria,” “were found to have competitive advantages over other female competitors,” and specifying that they weren’t given a testosterone examination, but were subject to a “separate and recognized” test. On Sunday, the IBA held a chaotic press conference during which the organization’s chief executive Chris Roberts said that Khelif and Yu-ting had taken chromosome tests in 2023 which “demonstrated both boxers were ineligible.”

However, at a press briefing yesterday, IOC spokesperson Mark Adams stood by the boxers’ right to compete and declined to comment on the credibility of the IBA’s tests. “I can’t tell you if [the tests] were credible or not credible, because the source from which they came is not credible, and the basis for the test was not credible,” he said.

Complicating matters further is the bad blood between the IBA and IOC. The Olympics governing body first suspended the IBA in 2019, before permanently severing ties with the boxing organization in June 2023 for failing to address concerns related to corruption, governance, and “financial dependence on Russian state energy firm Gazprom,” the Associated Press reports.

In fact, the controversy surrounding Khelif and Yu-ting is part of what Bach views as ongoing Russian interference at the Olympics — despite the suspension of the Russian Olympic Committee in October 2023. “What we have seen from the Russian side and in particular from the [IBA], they have undertaken already way before these Games with a defamation campaign against France, against the Games, against the IOC,” he said at a news conference on Saturday, where he also condemned the “hate speech,” “aggression,” and “abuse” directed at Khelif and Yu-ting on social media.

On Sunday, Adams noted that the decision to test Khelif at the 2023 IBA World Championships came after she defeated a Russian opponent, but said that he could not confirm whether the outcome of that match is what prompted the testing. When pressed for more information about the IBA testing and results, Adams declined to comment.

“There’s a whole range of reasons why we won’t deal with this,” he said. “Partly confidentiality. Partly medical issues. Partly that there was no basis for the test in the first place. And partly data-sharing of this is also highly against the rules.”

But this is only the latest chapter in a long history of personally invasive “sex verification” testing at the Olympics.

The unethical practice of ‘sex verification’

In sports, sex verification is a screening process used to confirm that an athlete is a woman, and not a man pretending to be a woman. This practice was introduced at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, initially in the form of a manual inspection of a person’s external genitalia, sometimes referred to as a “nude parade.” Cisgender men have not been subjected to sex verification of any kind.

“People only get really upset about the female classification for sport, and what it means to be female,” says Kathleen Casto, Ph.D., behavioral neuroendocrinologist and assistant professor of psychological sciences at Kent State University. “It’s historically a protected category, and if we didn’t have that category, women could be excluded from the Olympics because there would be many events for which no women would qualify.”

The modern era of sex verification at the Olympics began in the late 1960s, “out of fear that particularly Eastern Europeans were masquerading men as women in order to win Olympic glory,” says Jami Taylor, Ph.D., professor of public policy at the University of Toledo and an expert in LGBTQ politics and sports policies.

Following scientific developments and ethical complaints around genital examinations, World Athletics (WA), the international governing body for track and field sports, and the IOC introduced a new method of gender verification in 1968: chromosome testing for all women — and only women — athletes, explains Katerina Jennings, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Oxford with expertise in the ethics of testosterone testing in athletic.

WA ended the systematic sex verification testing of women athletes in 1992 but retained the right to test in specific cases, if suspicions arose regarding an athlete’s sex. “These ‘suspicions’ typically occurred on the basis of physical appearance, with women athletes who appeared more ‘masculine’ at risk of being selected for examination,” Jennings says. Seven years later, the IOC followed suit and repealed their blanket sex verification policy in 1999.

In 2011, the IOC and WA began using testosterone tests for ad hoc sex verification, because, according to the WA policy, higher testosterone levels “resulting in increased strength and muscle development” are primarily responsible for the difference in athletic performance between men and women.

“As a result, the testing of testosterone levels replaced sex and chromosome testing as the preferred method for determining which women athletes are permitted to compete in the women’s category in certain sporting events,” Jennings explains. Plus, there were systems in place for testing testosterone for doping. “There was already knowledge that testosterone provides a sport-based advantage when used illicitly,” Casto explains.

Along the same lines, the testosterone testing policy was rooted in the belief that women with atypically high levels of testosterone had an unfair advantage over their competitors. “The new WA regulations determined that any female-identifying athlete with a testosterone level above 10 nMol/L [nanomoles per liter] would not be permitted to compete in the competitive women’s category,” Jennings says.

For context, the average testosterone level for cisgender women is 0.5 to 2.4 nmol/L. However, women with testosterone that occur above that threshold naturally — including those with polycystic ovarian syndrome, hyperandrogenism, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, differences in sexual development (DSD) (commonly referred as intersex individuals), or transgender athletes — would be allowed to participate if they took action to artificially reduce the hormone.

“You can lower [your testosterone levels] with fairly noninvasive techniques, like getting on the oral contraceptive pill — which probably thousands of athletes are on at that level,” Casto says. “But that’s also still asking an athlete to change their body in a way they may not want to, and calling them out for something that hits at a basic aspect of your identity: that you’re not female enough because of an individual difference in your physiology.”

There are also issues of privacy and confidentiality at play. “In some cases, people don’t even know they have some sort of underlying variability that makes them have high testosterone until they do the tests, and that can be really shocking, because you discover you have a medical condition alongside the rest of the world,” Casto says. “It’s super invasive.”

In 2021, the IOC adopted a new policy stipulating that the organization wouldn’t exclude transgender athletes from competing because of perceived advantages, but instead would leave it up to each athletic organization to make that determination. This means that until it was permanently banned from the Olympics, the IBA decided who qualified to box in the Summer Games.

“The IOC, in terms of its testing on sex and gender, has evolved tremendously over the past 25 years,” Taylor says. “They went from the chromosome tests, to not testing, and then trying to create a framework for trans people in the early 2000s that gets broadened over time and to be more inclusive — and there’s pushback to that.”

The trans debate in boxing

It’s not surprising that much of the debate over sex verification in women’s sports has taken place within the context of boxing, Jennings says, where it may be more common to see women with what are considered “masculine” traits — like broad shoulders and muscular arms — than in other sports.

This discussion began long before Khelif or Yu-ting stepped foot in the ring in Paris. For example, the World Boxing Council (WBC), an international organization governing boxing, issued a statement in 2022 saying that it “firmly and unequivocally supports transgender rights,” then promptly announced plans to launch a yet-to-be-formed transgender league. “This decision is about safety and inclusion,” WBC President Mauricio Sulaimán wrote in a January 2023 blog post.

USA Boxing, the organizing governing Olympic-style amateur boxing in the United States, does provide a pathway for transgender athletes to compete, but only if they’re older than 18 and have completed “full” gender-affirming surgery, gone through multiple years of hormone therapy, and have four years of documented testosterone testing proving their levels are below 5 nmol/L for women and above 10 nmol/L for men.

Like the WBC, the “overriding objective” of USA Boxing’s transgender policy “is the safety of all boxers,” according to the organization. That’s also the basis of the Association of Ringside Physicians’ (ARP) position against competition between transgender and cisgender athletes in combat sports. According to the ARP position statement on the topic, “combat sports carry an exceedingly high risk for acute and chronic neurological and musculoskeletal injuries,” and “the mismatch in physical capabilities leave ciswomen and transgender men at risk if allowed to compete with opponents of the opposite biological sex.”

More specifically, the ARP claims that transgender women raise concerns about fair and safe competition in combat sports, “where muscle mass, strength, and power are key performance determinants.” Meanwhile, as Casto explains in a 2023 article published in Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, “no direct evidence shows that transgender and intersex women have a systematic sport advantage or that testosterone is the causal link.”

Interestingly, the ARP — which aims to prevent transgender and DSD women from competing against cisgender women — and those advocating for a more inclusive policy, view testosterone testing as an incomplete and imperfect measure for determining sports participation because levels can be manipulated.

But the future of boxing might be more inclusive — at least at the Olympic level. This week, the head of World Boxing — a breakaway organization founded in 2023 in response to the IBA’s banishment from the Olympics — publicly supported the IOC’s decision to allow Khelif and Yu-ting to compete, the AP reports. The boxing body, which currently has 37 member countries, is seeking the IOC’s approval to oversee the boxing tournament at the 2028 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

Fairness and the future of sports

While Khelif and Yu-ting were both allowed to compete under the Olympic rules — the speculation about their eligibility was largely based on their appearance — the conversation around their matches has brought up some lingering questions. At the heart of competitive sports, including the Olympics, there’s the question of fairness, ensuring “no athlete within a category has an unfair and disproportionate competitive advantage,” according to the IOC’s 2021 framework. But, as Jennings points out, this isn’t limited to a person’s sex, and also includes “physical or socioeconomic property advantages that lead to significant performance advantages,” like height, wingspan, hemoglobin levels, and access to top coaches, facilities, and equipment.

Along the same lines, Sigmund Loland, Ph.D., professor of sports philosophy and ethics at the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, makes the case that without some sort of genetic predisposition for a particular sport or skill, it would be nearly impossible to compete as an elite athlete.

Using Loland’s approach, any edge gained as a result of DSD should be thought of similarly to other advantages, like increased height in basketball, or growing up wealthy, Jennings says, and women with DSD should be permitted to compete in the women’s category. “It’s inconsistent to require only women with DSD to regulate their testosterone levels or face exclusion from sport on the basis of fairness, given that organizations continue to permit many other athletes possessing significant physical and socioeconomic advantages to compete without regulation or even scrutiny,” she says.