‘The Idea You Can’t Joke About Anything Anymore Is F-cking Ridiculous’

The Russell brothers had barely finished the signature routine of the act — a bit involving the boys dressed as immigrant servant girls that had traditionally left audiences in hysterics — before a soundtrack of boos filled the theater. They had crossed a line with their material, and now they were going to pay the price. The duo would essentially be banned from performing anywhere. They received death threats. Offers for gigs around the country were rescinded. Anti-defamation groups began organizing protests and threatening not just the Russells, but anyone who considered booking the brothers at all. One owner countered that he could book whoever the hell wanted, what with this being a free country and all. When the curtain came up on the Russells later that evening, a riot almost broke out in the venue.

Soon, the media joined the chorus of disapproval, saying that such an act was not just offensive but downright racist, and these performers deserved to be railroaded off the stage in perpetuity. Then other pundits began to stand up for the Russells, accusing the protesters of being overly sensitive. Couldn’t they take a joke? Besides, they said, you’re all trampling on the Russells’ God-given right to express themselves without fear of reprisal. And anyway, these self-proclaimed defenders of the First Amendment continued, if we give in to these pressure groups, it gives license for somebody else to declare that another “funny” thing off limits. Where does this censorious culture of “cancelling” end?! You can’t say anything anymore. Comedy is dead!

Welcome to the just-watch-what-you-say Nineties. By which, of course, we mean the 1890s.

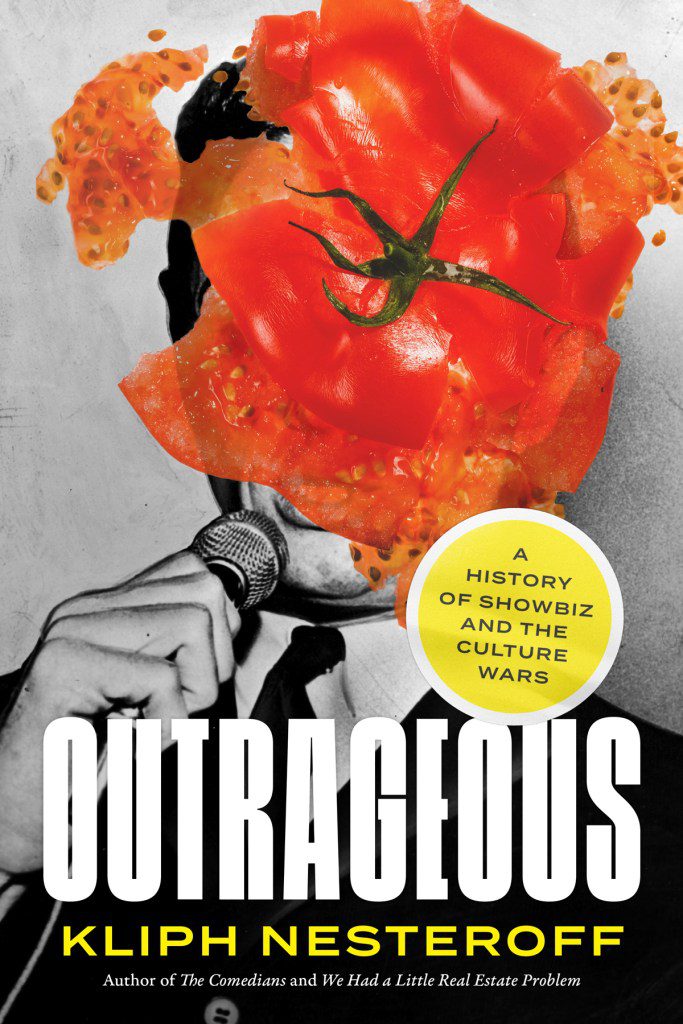

Courtesy Abrams Books

This scene of the Russell brothers becoming persona non grata on vaudeville for their incendiary use of Irish stereotypes — and then inadvertently becoming the focal point of the era’s culture wars, long before that term existed — shows up in the early chapters of Kliph Nesteroff’s NEW book Outrageous. Charting a century-plus of uproar that’s followed scandalous (or in many cases, “scandalous”) moments in show business, the author whisks readers on a tour of culture warfare involving everybody from blackface minstrels to the Beatles, the Frito Bandito to Fox News, Jerry Falwell to Jerry Seinfeld. Each chapter chronicles a roughly a decade’s worth of controversies, sketched out via trade-magazine reporting, editorial columns, and Nesteroff’s own connect-the-dots research. Some examples represent blatant bigotry. Others are handwringing, hard-right responses to how a new trend is the death of Western civilization.

“I’m asked to do a lot of interviews whenever there’s controversy in the world of comedy,” he says, sipping coffee in a Brooklyn cafe. A Canadian comic who started writing about vintage comedy for WMFU’s Beware of the Blog, Nesteroff made a name for himself as a funny-business scholar with his essential 2014 history book The Comedians. “Whether it’s Dave Chappelle or Hannah Gadsby or Matt Rife — that’s when the phone rings. Also, when you’re a touring stand-up comic, you tend to do a lot of morning radio. And I found myself getting asked the same question no matter who I was talking to: ‘Oh, well, you can’t joke about anything anymore now, right?’

“I got so tired of having to answer that question, because I don’t believe in the central premise,” he continues, before launching into examples. “In 1962, Lenny Bruce was arrested for saying ‘schmuck’ onstage. In 1990, someone was arrested for selling a 2 Live Crew album. In 2004, Janet Jackson exposed her breast during the Super Bowl, and look what happened. In the last few years, ‘W.A.P.’ became a hit song, the first episode of Euphoria featured like a dozen swinging dongs, and Pete Davidson — one of the most famous comedians in the world — has a TV show called Bupkis in which he’s masturbating and accidentally ejaculates onto his mom. There are no FCC fines, no protests, no calls for imprisonment. I tell people about Bupkis, and they’re like, ‘I haven’t heard of it… is that a real show?’

“So the idea that you can’t joke about anything anymore, or that we’re living in an age of free-speech oppression, is fucking ridiculous,” Nesteroff adds. “Far more taboos have been shattered than established. But it benefits people to keep going back to this playbook because it works. People say it’s all indicative of an anti-free expression clampdown, but it’s not. That’s just what they’ve been told it is. It’s all part of the same centuries-old cycle.”

And in Outrageous, Nesteroff traces how the backlash to stage shows, TV and radio programs, stand-up acts and rock and rap groups has always been politicized for good and for ill. Protests against minstrel performers, Thomas Dixon’s pro-KKK play The Klansman (and it’s subsequent film adaptation, The Birth of a Nation), and several iterations of Amos ‘n’ Andy fought against demeaning, degrading stereotypes of Black people; ditto the pushback against Irish, Italian, and Jewish stereotypes in the arts. Meanwhile, Puritan campaigners would rally against Mae West’s controversial stage show Sex to the extent that the comedian would serve 10 days of hard labor after being arrested during a performance. Nesteroff also reminds us of how formerly liberal comics like Steve Allen and “Brother” Dave Gardner were eventually recruited by hard-right groups to spread propaganda, and how the country trio formerly known as the Dixie Chicks were demonized by right-wing media after criticizing President George W. Bush.

And then there was the John Birch Society, the ultraconservative organization that claimed the Fab Four were a communist plot designed to weaken the morals of today’s youth and thus lay down the foundation for a pinko invasion on American soil. The group would distribute a booklet titled Communism, Hypnotism, and the Beatles to its members. It would also give us Paul Weyrich, a Zelig-like figure who’d become a key architect in the culture wars in the latter half of the 20th century.

“Weyrich is an interesting figure when it comes to the intersection of show business, politics, and the culture wars,” Nesteroff says. “When I was researching him for the book, I found that the earliest mention of him was around 1962, when he’s this young firebrand writing letters to the editor — the social media of its day — about how the commies are coming, Eleanor Roosevelt was this no-good, dirty commie, the U.N. is a communist front. And it’s a news story about how the Republicans of the day were complaining about him deriding other Republicans. He was considered way too extreme to be considered a conservative.

“But he was recruited by the John Birch Society, who didn’t have a problem with Weyrich saying that the Civil Rights movement was a Soviet conspiracy, or that the Civil Rights Act would lead to a tyrannical dictatorship. By the late 1960s, however, no one took the Birch Society seriously. Everyone from MAD Magazine to George Carlin to [Bob] Dylan had mocked them. Weyrich’s political philosophy was now completely out of favor.

“So what did he do?” Nesteroff asks. “He gets seed money from the Coors beer empire and started the Heritage Foundation, which is still around today. You see them on TV shows all the time now: ‘So-and-so is a Senior Fellow at the Heritage Foundation.’ Ok, but: What’s the Heritage Foundation? What the fuck is a senior fellow?! The host never tells you that, but people take this person seriously because they’re wearing a bow tie. But it’s still the same fucking bigots who stumped for the Birchers. Weyrich also co-founds the Moral Majority with Jerry Falwell, which is a huge part of the Eighties culture wars. The Council for National Policy, which advised Donald Trump in 2016? Weyrich founded that, too. He didn’t give up. He simply rebranded.”

Outrageous gives us dozens more examples of how these same arguments keep getting resurrected, and the same straw-men used to demonstrate the decline of “moral” standards. The only thing that really changes, Nesteroff notes, are the names of the targets and the language used to attack them. “What is ‘woke’ but a new way of saying ‘politically correct?’” he declares, laughing. “And what does that term even signify anymore? I knew that the phrase had lost all meaning when I heard Donald Trump and my friend Lewis Black had both complained about political correctness in the same year. I’m not 100-percent sure, but I’m pretty certain Louis and Trump don’t agree on anything. Yet they’re using the same language. Or when you hear people use the words ‘liberty’ and ‘freedom’ when they’re talking about taking away women’s rights and rolling back civil rights’ legislature. When those types of things stop meaning anything, then they can mean everything. It will fit whatever you want it to fit.”

The more you read about these recurring controversial incidents, politicized responses, and inevitable counter-responses in Outrageous, the more you realize that show business and the Culture Wars, Inc. contingent have always been bedfellows, regardless of what side of the aisle the fight falls on. We’re still fighting against bigoted racial representation, and what is and isn’t appropriate to say. We’re still debating what to do when lines are crossed, dissecting which lines should and shouldn’t be crossed, and defending those who cross them for a variety of reasons. Progressives and conservatives still police sensitivities in the name of their base demographics, even if the equivalencies are often false. We’re still locked in the same rinse-repeat outrage cycles.

“It’s funny, because I’ve talked to a number of people who’ve read the book,” Nesteroff says. “And a lot of them aren’t sure about how they are supposed to feel about things when they’ve finished it. Like, are they supposed to be depressed over the fact that things never change despite our optimism? Or are they supposed to feel better about things because they are similar to the past, and we got through it back then?

“I don’t claim to have the answer,” he notes. “But I can tell you a story. The night of the Oscars, when Chris Rock was slapped — everyone online was going, ‘Holy shit, this is unprecedented.’ And I went to newspapers.com, and I typed in ‘comedian slapped.’ And I immediately got all these results back, some dating over a 100 years ago, about a comic telling a joke, then someone rushes the stage and smacks him. I began posting these on Twitter, and people went nuts. I do think there’s some sort of endorphin rush we get when we recognize repeating patterns. There’s a weird joy in going, ‘See? This has all happened before.’”