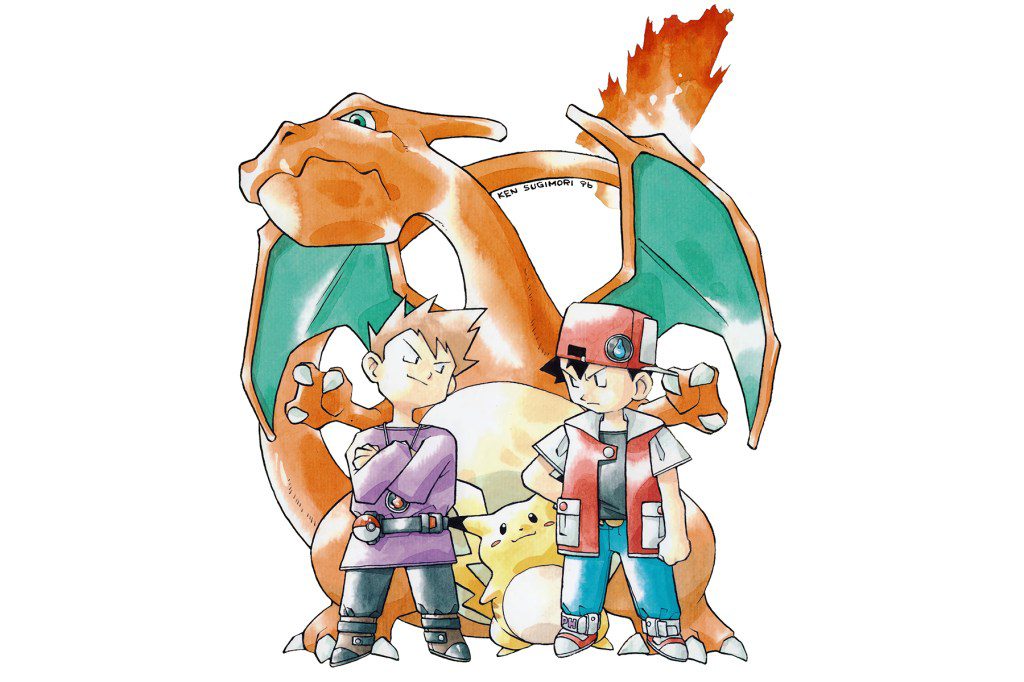

The Digital Orphans of ‘Pokémon’

It’s difficult to describe the effect Pokémon had on children in the late 1990s to someone who wasn’t there. Today, Pokémon is the highest-grossing media franchise ever, so ingrained in global culture that it’s ever-present. When it rolled out in the west 25 years ago, however, it did so into a world before franchise oversaturation, spreading like a fire burning through a dry forest so that even the uninterested couldn’t help but see.

After Pokémon Red and Pokémon Blue kicked off the first generation in the UK in 1999, my fourth grade playground turned from disparate games into a unified hub of swapped trading cards almost overnight. I ruined my eyes squinting into a Game Boy trying to “catch ’em all” and rushed to catch SM:TV Live and the latest episode of the anime with it. Pokémon was everywhere; for children like me it was everything. If once we kept time by the school bell and the schedule of Saturday morning TV, now it didn’t matter. There was before Pokémon and after.

If the Pokémon crazewas rapidly becoming unstoppable, however, my excitement burned out just as fast. Peaking with the video game’s second generation, 2003’s Gold and Silver, I was over it. I moved on, leaving relics of my wanton enthusiasm sequestered on abandoned cartridges and binders of Pokémon cards, waiting to be rediscovered.

What would I rediscover? That was something I wouldn’t find out for two decades. Not just from the Pokémon I orphaned on my own old games, but through the universal stories that emerge when we examine each other’s lives through the save files we leave behind.

A slow return

Though I had grown out of Pokémon, its ubiquity makes it impossible to forget. Even if I wasn’t ready to revisit my old Pokémon, I still thought fondly of the days of link cables, printing pixelated pictures of Vulpix from a Gateway PC to show friends, and calls over fuzzy landlines to share tips on cloning Pokémon. The internet has made gaming more socially accessible, even if that socializing is more abstract — more anonymous. Back then, it really felt tangible.

Those days were long gone by the time I picked up my next game, Ultra Moon in 2018. Yet, it threw me back to a childhood spent huddled over a Game Boy all the same (albeit replaced by the dual screens of a 3DS). If the internet has removed some of the immediacy from gaming together, it’s made Pokémon more connected. It meant those Pokémon I met in Generation 7’s Alola region would not suffer the same ignominy of being abandoned on lost cartridges as those I met in Kanto and Johto in Generation 1 and 2.

Gen 1 Pikachu is unrecognizable to modern fans, but rings of nostalgia to older ones.

Nintendo; Game Freak

Instead, they can live in Home, Nintendo’s paid Pokémon cloud storage service, which has even given catching them all new meaning by giving room enough to hold every Pokémon — known as a living Pokédex — and then some. To truly catch them all, however, I’d need to catch up. Gone are the days of 151 Pokémon; now there are 1,065 spread over nine generations. But no matter how much my enthusiasm returned, one of those generations always eluded me.

Black and White, along with their immediate sequels, make up Pokémon’s fifth generation. Thanks to 2000s nostalgia, heightened since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic and the games’ relative scarcity, the second-hand prices of these DS cartridges have ballooned. Even counterfeits can sell at, or above, the games’ original retail price. That inflation, fortunately, is yet to reach Japan, making it the best region to begin the search. I don’t speak Japanese, but hoped to muddle through as I tracked down a reasonably-priced copy of Pokémon White to complete my living Pokédex. But if I thought language would be my biggest obstacle, I was wrong.

The archive

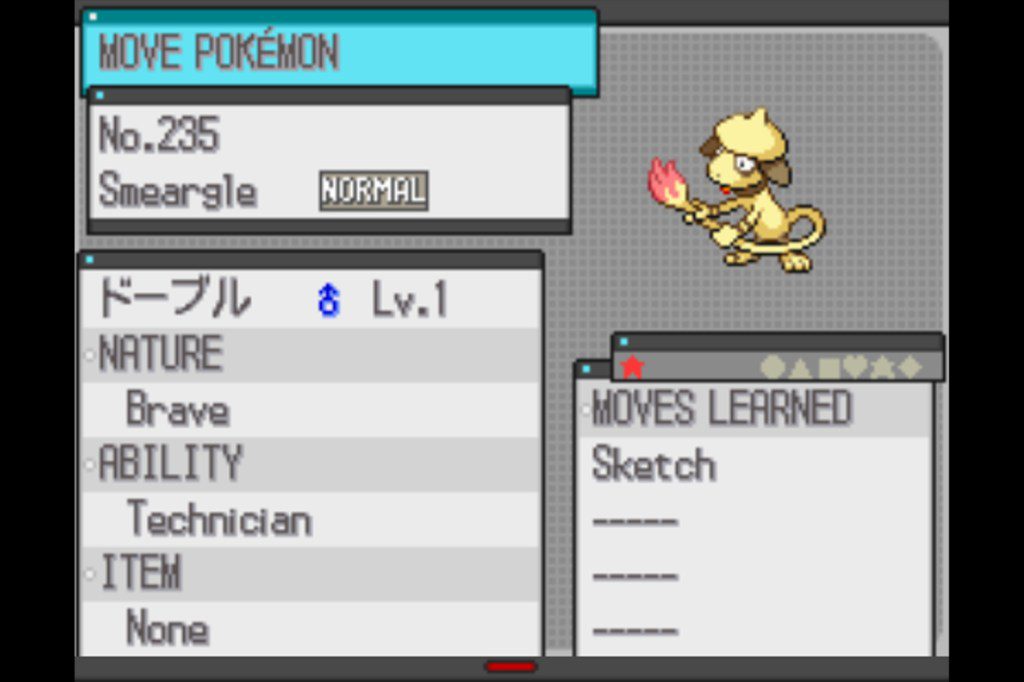

When the cartridge arrived and I inserted it into my DS, I found the previous owner’s save intact. Normally, deleting this would be a quick fix. But this player — whose playthrough spanned most of 2012 — had accumulated 454 Pokémon in their Pokédex. Their boxes were full of them, including a shiny Smeargle from Platinum, a host of Pokémon from previous generations, and 73 Magikarp bred in and traded from Black 2.

A shiny Smeargle.

Nintendo; Game Freak

Through the DS screen, I was examining a time capsule of a life different to mine but made familiar by Pokémon. It felt wrong to wipe it — to throw away 304 hours of someone else’s experience. I felt responsible for their Pokémon, orphaned when the player had discarded the cartridge, which had landed in my hands entirely by chance.

I was also curious. From then on, I’d pick up cheap Pokémon games when I found them, just to look inside. It became a hobby: save-file archaeology. Some weren’t as interesting. A wiped copy of Gold or a Yellow saved in the starting bedroom and abandoned. Others, however, told more interesting tales. Even if it was only the feelings those stories motivated in me.

I empathized with the players who started (or maybe restarted) games only to lose enthusiasm a few hours in. I also appreciated why one player, having gone through the laborious process of completing Omega Ruby’s national Pokédex of 721 Pokémon, moved every single one of those Pokémon up and out — leaving behind only one Pokémon: a level 29 Gloom.

What psychopathy was behind the Magikarp farm?

Nintendo; Game Freak

There was a copy of Sun that included an almost complete Generation 6 living Pokédex. This player had also abandoned a shiny Rayquaza — that being a rare color variant that every Pokémon possesses — with the original trainer listed as “WHF15,” suggesting they’d attended an in-person event at Pokémon Center Hiroshima in 2015. In fact, they’d attended multiple events, in-person and online, only to leave those Pokémon behind, including a 2011 event Entei.

Two copies of Pearl told similar, though opposing, stories. In one, boxes of Bronzor signaled a lengthy hunt for a rare shiny variant, the success of which — marked by a shiny Bronzong left in the player’s party — encouraged them to do the same for Feebas without success. The other included box after box of Chansey and their eggs. It smacked of a shiny hunt that ran out of steam. The tragic kicker: When I hatched the remaining eggs, one produced that elusive shiny.

Of course, you don’t examine so many Pokémon games without finding cheaters. Another copy of White included a Level 100 legendary Reshiram impossibly caught in a Master Ball on Route 4. Not only are Generation 5’s box legendaries usually caught at an area called N’s Castle, Reshiram isn’t available without trading in White. Then there’s a copy of Sapphire that opens with the player surfing on land not far from a Pokémon Center full of hacked shiny Pokémon.

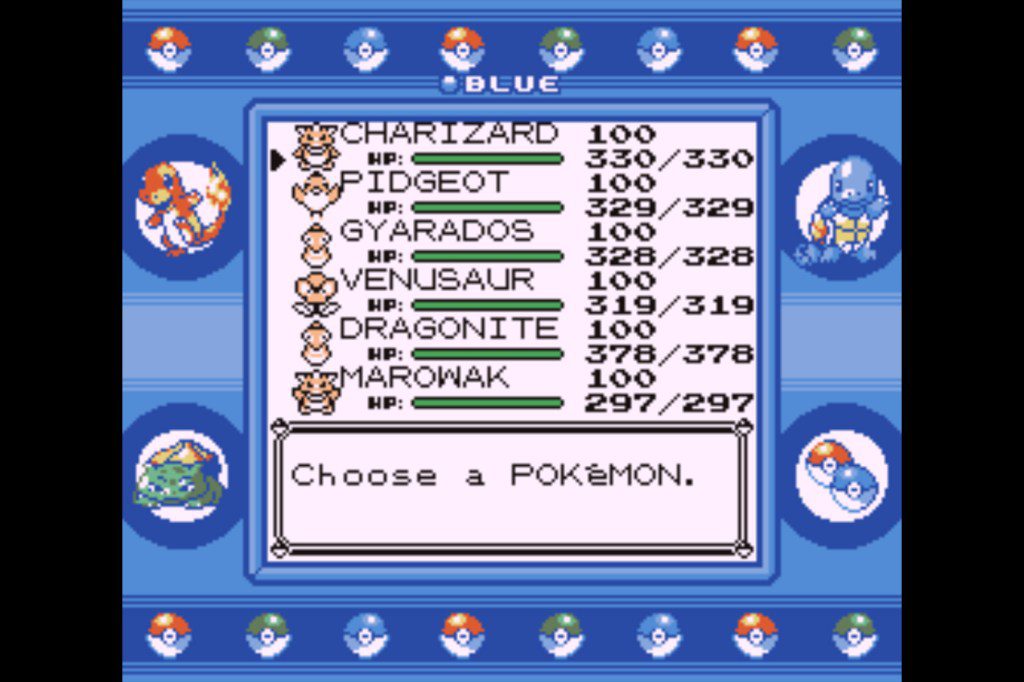

Hours of care poured into this Gen 1 classic roster, only to be lost in time.

Nintendo; Game Freak

In no time, I had in my possession a library of other people’s stories. We were all disparate —disconnected — and yet joined in our Pokémon experiences. I saw myself in their decisions, much as they’d see the same if privy to my own life in save files. I started to wonder what might echo on those Master System games, on stray N64 cartridges, and in my own Pokémon. What might those old games say about who I once was — about who I am?

A study in Scarlet (or maybe Blue)

The attic in my family home is an uncomfortable space. Low-roofed, a maze of plumbing, with cladding hanging from the sloped ceiling like stalactites. It’s a suffocating mess of black bags, disintegrating cardboard boxes, and vacuum-packed clothes over which one must clamber like a caver.

So much of our past is retained here in a room stuck looking back in time. It’s not sentimentality that preserves it, but a lazy devotion to filling space. Toolboxes of Warhammer, scratched CDs, suitcases of rotting paperbacks, and clear boxes of faulty consoles: an SNES, a Nintendo 64, even a Barcode Battler.

I don’t know what I expect to find. I’m sure my old games are lost, either hidden under mountains of rubbish or thrown away. Yet, improbably, in a pile of Game Boy cartridges under a PlayStation I have no recollection owning, there it is: a copy of Blue. The label has faded, the edges white with chipping, but it works.

Each cartridge is a time capsule peering into a slice of a human life.

Geoffrey Bunting

My original playthrough, started Christmas morning 1999, is long gone. My brother overwrote it when I switched to Red because it had Charizard on the box, before I came back to truly “catch ’em all” using both. Still, this playthrough isn’t so removed from my first. I started with Charmander, kept a Pidgeot, and filled my team with Gyarados, Dragonite, a traded Venuaur, and a Marowak. A team that is dramatically, pleasingly, infantile.

Here was a child who used the sun of muggy summers to illuminate a dim Game Boy screen, beholden only to the rule of cool. Now, I’d be more exacting. With so little time to play, efficiency takes precedence. Back then, the only limit to my playtime was the number of AA batteries in the house. Had the owners of all these cartridges done the same? Perhaps without having to deal with a non-backlit screen, but had they sequestered themselves indoors to play Pokémon while exasperated parents begged them to go outside? Have things really changed at all?

Most people won’t go back to relive these memories, but in data they remain.

Nintendo; Game Freak

After all, Isn’t that what all of these are? Looking into my own past through Pokémon, I realize these orphaned save files aren’t totems to moments in time, but records of people changing. They’re like height markings on a door stile or a long-forgotten diary but for a more digital age — nostalgic, for sure, but also more instructive. It’s a privilege, in a way, to be granted, by chance, a library of these stories that can tell so much about the people behind them. Stories about growing up, moving on, and changing lives to which we all could relate, all told through the strange hieroglyphics of Pokémon sprites.