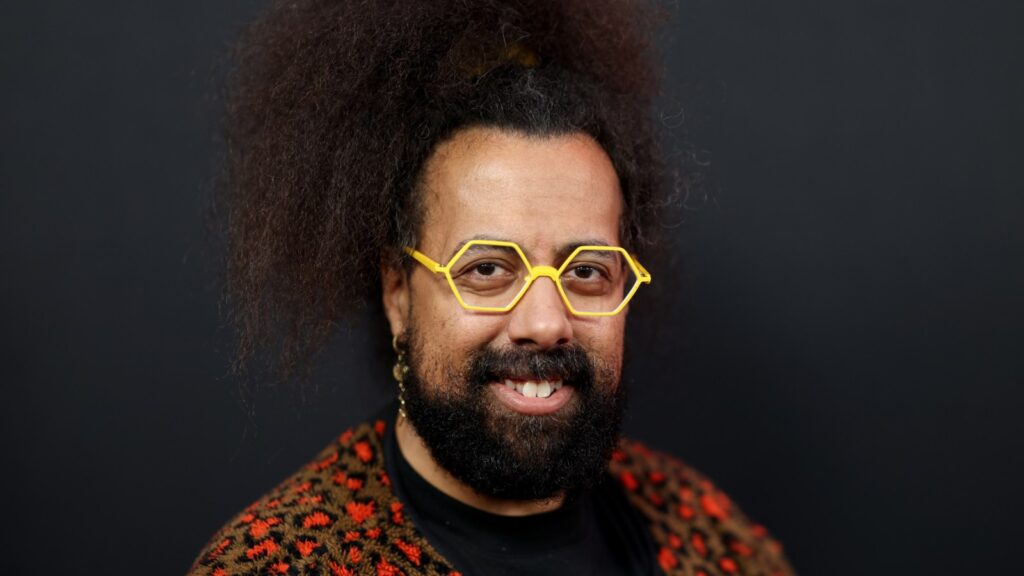

Reggie Watts Is in the Right Place at the Right Time

Reggie Watts is pretty sure we’re living in a simulation. Or that he is, anyway.

“Highly probable,” the multifaceted artist, 52, says over his tuna salad outside a café in L.A.’s Silver Lake neighborhood. Our server happens to recognize him and compliment his work. The pleasant encounter seems a small example of the lucky “synchronicities” that inform Watts’ belief in a Matrix of sorts: his career path has involved often “being in the right place at the right time,” from “Seattle in the Nineties, then moving to New York in 2003, when the third wave of alt-comedy was happening just in one club [Rififi in the East Village] before it exploded.” He lived and collaborated with Jacob Lodwick, the co-creator of Vimeo, just as viral videos started taking off in the mid-to-late aughts. “Just being a part of renaissances at different stages in my life,” Watts says. Most recently, he’s cast a critical eye upon the age of algorithms and automation — when he calls before our interview to say he’s 15 minutes away, he mimics the robotic voice of an AI assistant.

But given the wealth of his experience between those first indie gigs and an eight-year run as the announcer and bandleader for The Late Late Show with James Corden, which aired its final episode in 2023, Watts also has the chance to reflect on the past. Just not in any straightforward fashion. A master of disorientation whose sets combine improvised comedy, vocal effects, and musical riffs into a vortex of surrealist entertainment, he performs his new special Never Mind as if he and the audience are living in the late 1990s. (It debuts July 20 on Veeps, a streaming platform that specializes in live music events and launched a comedy vertical last year.)

The result is a sort of nonsense TED Talk on obsolete technology like minidisc players and the Sega Dreamcast, presented as if these are cutting-edge gadgets ushering us into a utopian 21st century. Watts muses about the “latest” digital innovations in audio gear, internet access, and gaming while he speculates on where innovation may take us next, never dropping the unstated premise that we have yet to experience the online 24/7 present as we know it. He also works in his trademark musical flights of fancy: Watts is renowned for using analog tools and instruments to create beatbox rhythms and vocal loops that he layers into songs you swear you’ve heard before — except he makes them up on the spot.

Watts observes there’s a powerful nostalgia attached to the old technology he discusses in Never Mind. “We’re starting to see Gen Z and Gen Alpha kind of going back” to pre-smartphone devices, he says, noting that younger people in his orbit have embraced the Canon PowerShot, a line of digital cameras dating back to 1998. “It’s stuff that we connect with as human beings, as opposed to, like, abstract flat glass screens with no tactility to them. I celebrate that time period, because I think it was technologically, on an interface level, superior to what we have now.” The format of the show, he explains, gave him the chance to act out the “nerdy fantasy” of detailing his passion for that dated hardware. Naturally, he mocks Microsoft’s “Clippy” while he’s at it.

Of course, lots of the humor in Never Mind comes from a misplaced faith in computers and Watts’ performative optimism about what Silicon Valley will achieve after Y2K. In one riff, he marvels at the possibility that we’ll one day be able to experience video calls, something that certainly sounded cool a quarter-century ago but now tends to evoke the horror of endless Zoom meetings during the pandemic lockdown. Watts strews the performance with the subtly smug pronouncements of an industry trend-hunter, so that you occasionally feel like you’re being sold a stale corporate vision. “All I can say is that the future is in Sweden,” he remarks cryptically at one point. “That’s all I’m gonna say. Maybe 14 years from now, you’ll be like, ‘Oh, I get it.”

Watts would love to do a show like this for every decade — he imagines a 1980s set in a big theater, wearing a leather suit like Eddie Murphy wore for Raw. He says that without the day job of the Late Late Show, he could record a new special every month, since each is almost entirely improvised. It’s this open-ended approach that allows him to cast a spell over a crowd, digressing from one subject to another, fiddling with his machines, and veering into nonverbal sounds or different accents to eventually locate an intuitive groove that clicks for the entire room.

The songs become extensions of his shaggy stream of consciousness. After observing that some people are getting up to go to the bathroom, he migrates over to the keyboard and seamlessly segues into a smooth R&B number that includes the lyric “Everybody got a bladder and it matters, yeah.” Elsewhere, he erupts into an dead-on a cappella impression of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and conjures a spacey trip-hop tune of nonsense syllables that could easily serve as a bonus track on Massive Attack’s Mezzanine.

“I’m just trying to find what’s most appealing, what feels really good,” Watts says of his exploratory, jazzy technique, which encompasses almost every genre. And after listening to and playing music for so long, he can project a certain confidence that allows the crowd to follow him toward a familiar sensation. “When you’re relaxed and you’re like, ‘You know this,’ people will be like, ‘Yeah, I do know this,’” he says. “It’s kind of like hypnotism. I’m trying to essentially infect people with fun.”

It’s hard not to notice, too, how Watts’ unique talents, honed to deliver sonic twists and surprises, resist the dominance of the streaming era. He is dismayed by the heavily corporatized state of the music industry today, in which similar pop songs blur together and algorithms keep us locked into genre bubbles, with no hope of stumbling upon radically different and groundbreaking artists. Watts recalls getting “grumpy” in his last couple years of late night duties, when what he calls “spacebar bands” would guest and have their “generic” music piped in from a laptop instead of playing live. “That started to get under my skin,” he said. He has since decided to remove his own music from Spotify, and he has a plan to spoof the kind of artists who blow up on the platform, while selling his work directly to the listener: a three-song demo that he’ll whip together with a producer in just an hour.

“The idea is to make songs that are comparable to hit songs,” he says. “But we make it in an hour, to show you how simple and how easy that music is to make. So that kind of takes away the preciousness of it, and undercuts the work that goes on. You’ll see how the entire song is made.” Which may be the simplest way to describe Watts’ appeal, even when he’s mocking the high-sheen gloss of today’s inescapable chart-toppers: when you watch him, you’re getting the entire creative process, not a frictionless final product.

“Music is one of the most transformative art forms, [and] the fastest,” Watts says. “How fast can a song change your mood?” He then offers a more earnest prediction than the ones we hear in Never Mind: “The future is in music that people can relate to, and I think that people are going to get tired of algorithmic music,” he says. What does he want us to discover beyond the cycle of samey recommendations? “Weird shit,” he says.

For someone whose bewildering on-stage persona stands so far apart, there can be no other answer.