‘Prince of Persia’ Is Back With a New Sound, Straight Outta Iran

When it was released earlier this year, Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown surprised players not just by resurrecting the long dormant franchise in stellar fashion but doing so by returning to the series’ roots. Rather than playing it safe with emulating the 3D formula of the fan-favorite Sands of Time trilogy that most modern gamers are likely familiar with, the developers at Ubisoft Montpellier opted instead to go all the way back to the original game’s 2D perspective for a more focused throwback to the exploration design of the late Eighties and early Nineties.

But despite going back to the basics, modernization was firmly on the mind of the creative team, led by director Mounir Radi and producer Abdelhak Elguess. One of their top priorities was to pay homage to the historical culture of ancient Persia without wading into the kinds of clichés perpetuated by Western media. To do this, the tone needed to feel authentic, while serving larger-than-life fantasy story they wanted to tell. One of the key elements to accomplishing the balance deftly was through the game’s music.

To find the right alchemy between a faithfully “Persian” experience that also evokes the thrills of a blockbuster action title, the team at Ubisoft Montpellier turned to two very different composers to score The Lost Crown: Iranian-born musician Mentrix (real name Samar Rad) and British composer Gareth Coker. Mentrix, whose eclectic sound blends traditional Iranian instrumentation with synthy modern flourishes, had never scored a video game before, but brought to the table an invaluable cultural perspective. Coker, the award-winning composer behind games like Ori and the Will of the Wisps and Halo Infinite, provided the bombast expected of an adventure game.

Their journey finding the right notes to bring the game’s score to life is now chronicled in the mini-documentary Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown – A Musical Odyssey, premiering exclusively on Rolling Stone. Watch the full video below.

To celebrate the streaming release of the game’s soundtrack, Rolling Stone sat down with both Mentrix and Gareth Coker to discuss the complexities of bringing the world of Prince of Persia back in a modern light.

One of the most celebrated elements of Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown has been how it respects the historical identity of ancient “Persia,” without sliding into cliché. How did you approach crafting music that felt authentic?

Mentrix: Being Iranian, obviously, the brand — even if you haven’t seen the film or any of the franchise, you feel a connection to it. This is my heritage. So, it was very appealing to me to be able to work with a franchise that has got this credibility that it has. But what was most important — so fantastic — the golden opportunity here was to work with a team at Ubisoft who were so aware of all the stigma and the clichés and all the mistakes that had been done, and they were really looking for originality. And they really wanted to help me bring that to the table.

I was here to do music for these environments that are inspired by the history of a land, of region in the world that has its own culture and sounds, but it’s an inspiration so you’re also able to go beyond. This is the great opportunity with fantasy.

Gareth Coker: I think between myself and [Mentrix], we had to very distinctive grounds covered. Clearly, she was brought on board to represent the “Persian” side of the game, because that is her background. No matter how hard I study that music from that part of the world, I’m never going to be even close to as good as someone whose natural background has music from that region.

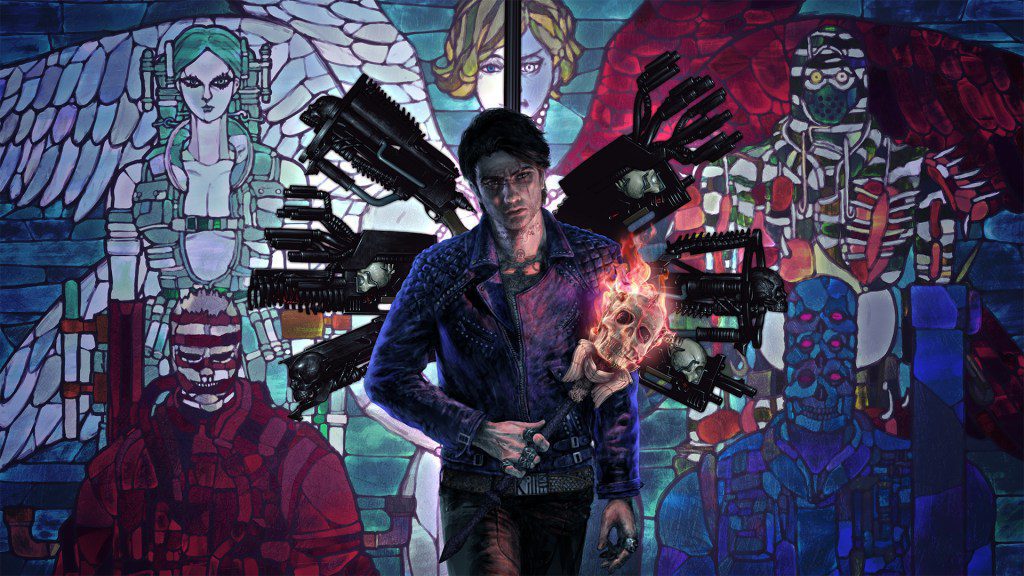

That’s where everyone on the team felt like, “Okay, we’ve got this Persian base to build upon but now [we] need something extra to take it completely over the top.” And if you’ve played the game you know that it’s not a “Persia simulator.” It’s very much set in a world that feels like ancient Persia, but the way the game is presented means we moved to some very dramatic and over the top sequences — and particularly in the final boss fight — I remember it came in, I’m like “This is absolutely insane and wild.”

Ubisoft

Is that a testament to having a more diverse development and art directing team?

Mentrix: [The team], they all had their own stories, and they are also very aware of the fact that there are differences between something that comes from Tunisia, something that comes from Turkey, something that comes from Iran, [Afghanistan] — this is not all the same, you know. Morocco, Algeria, there are differences. This awareness was just everything you needed to avoid all those clichés. They knew exactly that [they] wanted to have someone Iranian, who knows how to bring that heritage, that sound, but with influences of the west, with a touch for electronic music or a certain sound production that is modern that we feel that our players relate to.

I feel that we avoided those cliches that are often like, “Oh, Persia,” and you start doing something that sounds very Arabic. It’s like thinking, “Oh, Orient,” and you’re in Japan, and then you start doing something that’s Chinese.

Mentrix, your style of music feels very much like a fusion of traditional Iranian sounds with more modern electronic twists. What kinds of music did you gravitate toward in your youth?

Mentrix: I was a child of the Islamic Revolution so, in my childhood, all you have is two channels on TV. In rotation, they’re broadcasting religious music or just religious chants. On the radio, occasionally, you have some classical Iranian music. But for a long time, this was associated so much with state music that it was not something that, as a youth, you would be drawn to listen to. The classical music just seemed so out of reach and so old and so dated.

So, my early childhood is really like post-war, and that environment is really a vacuum. I have clear memories of the sounds that were associated with that time. A lot of bombing and a lot of earthquakes. Everything is just very, very intense and oppressive and, on top of that, you have all these sanctions [and] rules, and so it was a period where music was very difficult to access.

When I moved to Paris for my studies, one of the first types of music I was exposed to was jazz, and that just blew my mind. [That] just really opened the whole world to me and my fascination for music. It just is this thing that was not there, and then it was there. [And] then I moved to the UK. I fell in love with punk, just the Sex Pistols all the way to the Yeah Yeah Yeahs.

Ubisoft

What were the challenges of trying to create an “epic” sound for a game that, from a technical perspective, could easily feel small by the nature of being designed in 2D?

Coker: I think there is kind of a knock on 2D games that they can’t be epic, and they can’t be over the top. In 2.5D, however, one of the coolest things that they did on this game was shifting the camera in for cinematics. That just brings you closer to the characters, and it’s funny because you think when you get close to the characters, you might want to go more intimate with the music, but actually these characters are so over the top that’s actually and excuse to go big with them.

It feels like a comic book come to life; that was my immediate reaction. And actually comic books and anime were direct references for us on this project. They’re like, “Make it more anime.” And I’m not saying it was exclusively, “Make it like Japanese anime,” because it’s also like Western comics as well, but it’s just having that feeling of being overdramatic.

Mentrix: There were a lot of reference from manga, Japanese stuff. It was part of the brief. We want to have a feeling that we are in this environment, but also the game had this very manga appeal. It’s like, “How do you incorporate that?” And so, obviously, I’m thinking electric guitar, shredding, you know, Eighties. Just thinking, “What’s the palette? What is it that we want to go for?” Then it’s like cooking, you make it and you taste it, and everybody says, “Well, should we add more?”

Ubisoft

In what ways did you stretch beyond your comfort zones to fit the tone of the game?

Mentrix: My music, [it] really comes from a spiritual place, a spiritual practice. This project was an opportunity to explore other things. You know, chord progression – which is something I wouldn’t use. It’s so Western, like why would you do that? [Laughs] I realized that I hardly even really paid attention to it.

I did some boss fights. That was just something I had never done before. And I love my metal! I love Gojira, I love Meshuggah. Swan’s an all-time favorite because it does sort of have that hypnotic vibe. [But] I really had to go there and come out of my hypnotic zone. There’s definitely been an effort to do something more active, with more dimension, with like mountains and a range of emotions.

Coker: I think one of the things [was] the boss fight with Orod, [it] was the first track I did for the game. And there’s nothing else like that track on the entire album. I think boss fight music is important to have its own identity, it doesn’t necessarily need to sound exactly like the rest of the score from the game. Orod’s music is basically a rock track with orchestra. Most of the track is in 5/4 [time signature], which is a very unusual time. We wanted it to feel like the boat was constantly rocking, that you’re fighting on. It’s quite an unpredictable fight, and so I was like, “Let’s just make it rhythmically weird.”

As a Metroidvania-type game, The Lost Crown is an experience where players will explore the world and experience the music for extended periods of time. What does the genre afford you creatively as a composer that others don’t?

Coker: I actually think this style of game gives you a lot of freedom as a composer, and I don’t think it’s a coincidence that some really popular scores of the last decade come from the Metroidvania genre. [You] get to write more music, but [it] also gives the player space to enjoy it because they’re not overstimulated as they might be in a 3D game.

In 2D, there’s enough space for everything to breathe. I think that, combined with the Metroidvania style of game, allows for a natural progression in the music: unlock more abilities, do more stuff, go to new places — it just allows for a natural progression. Whereas [in an] open world, it’s like you’re constantly back and forth and revisiting. And I know there’s “reach reversal” in Metroidvania, too, but you’re often going back with a new abilities so it feels psychologically different when you’re exploring.

Ubisoft

What was your biggest takeaway from working on The Lost Crown?

Coker: Go big when it actually matters. [In Prince of Persia], I think the exploration music is pretty cool. It sets a vibe. But then when we go big, we really go big and it feels earned because it’s not big all the time. A saying I like is, “When everything is epic, nothing is epic.” Because there’s no scale. And I think one of the things I like about the Prince of Persia soundtrack the most is the dynamic range of the soundtrack. We have the quietest of quiet, and we have the loudest of loud, and you get the full experience across the game.

Mentrix: What I discovered through this process is that gaming is much more emotional than I thought. And having access to that and being given the freedom to explore that — that was really something. What I had on my mind and my heart all the time was to really deliver on that, and to become closer to the story and the plot and the characters.

[It] was very difficult, especially at the beginning because when I arrived with the words, only concept art, things were not that developed. I was surprised, I thought that music comes a bit later, but this is how I discovered that it’s not an afterthought. [We’re] all moving toward this together.

Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown is available on PlayStation 4 & 5, Xbox One & Series X|S, Nintendo Switch, and PC. The soundtrack is now streaming.