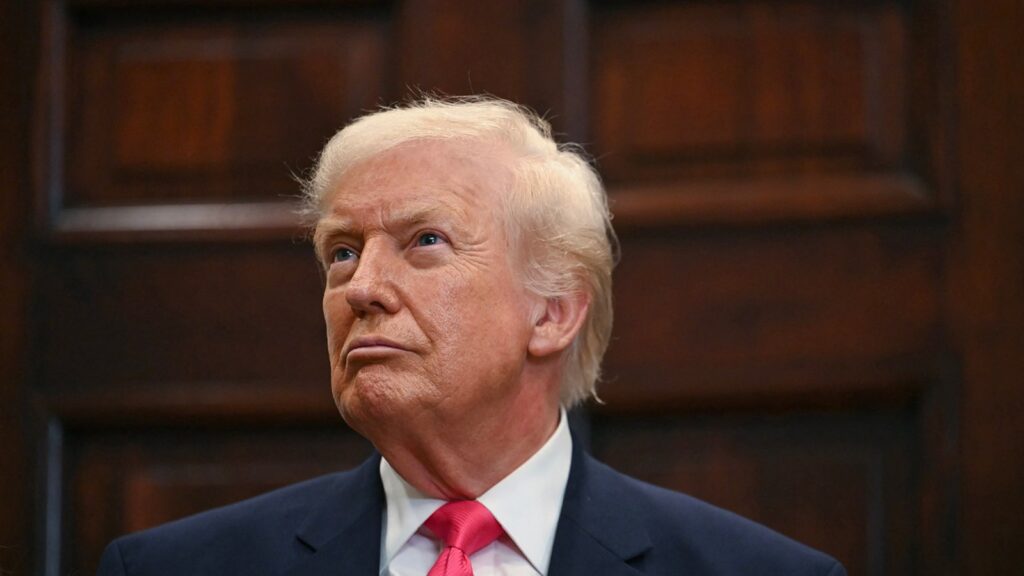

PlayerUnknown Changed Gaming with ‘PUBG.’ But What’s Next?

PlayerUnknown‘s Battlegrounds, best known as PUBG, continues to harness hundreds of thousands of players since its 2017 release. The battle royale sold 40 million copies in its first year, and reached over 3 million concurrent players on PC via Steam in 2018 — a record that still stands to this day, followed closely but still trailed by the likes of Counter-Strike 2 (2023), Black Myth: Wukong (2024), and Palworld (2024).

PUBG was the result of the collaboration between game studio Krafton and developer Brendan Greene (otherwise called PlayerUnknown), who led the project. Greene then parted ways with Krafton to form PlayerUnknown Productions in 2019. Instead of another take on the battle royale genre, this new studio has been working on several projects, most notably a survival game called Prologue: Go Wayback!, which are envisioned as pieces of a bigger puzzle. The final piece, Artemis, is aimed to be the culmination of in-house technology that could host millions of players inside large-scale worlds at once.

Rolling Stone recently spoke with Brendan Greene about PlayerUnknown Productions’ three-game plan, how the studio is leaning into the concept of the metaverse for Artemis, and the survival genre inspirations for Prologue: Go Wayback!, from Don’t Starve Together (2016) to broader walking simulators.

A three-game plan

PlayerUnknown Productions is working on multiple projects simultaneously. Prologue: Go Wayback! and Preface: Undiscovered World are standalone experiences, but they’re also serving as testing ground for the studio’s in-house technology that will eventually power Artemis. The end goal is for this technology to be able to generate massive scale digital spaces that can host millions of players. But what does this all mean, exactly? And, more importantly, how does Greene intend to deliver on his lofty ideas?

“The three-game plan kind of started with this idea that I can’t make this massive world all at once,” Greene says. “Trying to do Earth-scale with millions of people with lots of things to do is just too much to attempt at once. So we thought, ‘Okay, let’s start small.’”

The studio began working with the game engine Unity, and then moved to Unreal sometime in 2022. One of the first obstacles to overcome involved testing the terrain of the world; hence the idea of Prologue: Go Wayback! being a survival game. The genre, led by the likes of Minecraft (2011) and Rust (2013), to name a few, has players gathering resources from diverse biomes to keep their hunger in check, create shelters, and survive hardships. The usual appeal of these games involves having a newly generated world each time players create a session. At the start, the team at PlayerUnknown Productions was able to create a 100 by 100 kilometer world, which has served as a foundation for the ongoing game ideas to further test things out.

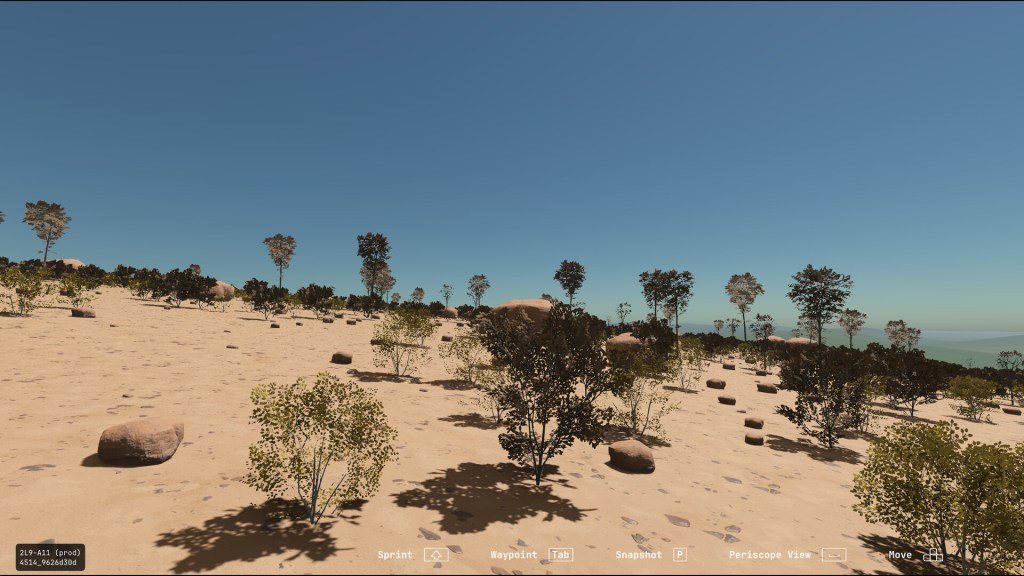

Prologue: Go Wayback! is a survival game that builds the procedurally generated foundation of Artemis.

PlayerUnknown Productions

To Greene, the three-game plan makes it so the team is working on the larger vision in stages, each adding “another piece of the broader puzzle” to get closer to Artemis. Laying the terrain, adding multiplayer on a small scale before it’s gradually ramped up, and testing interactions and game systems later on. “We’re just stepping it up, step by step, trying to test out each stage before moving forward,” he says.

In the case of the likes of Rust or DayZ (2013), the projects were first launched in early access. The full release took around five years for both projects. Early access offers a chance to play a game before the official launch, with studios releasing updates over time and making improvements to the mechanics based on user feedback. Greene and the team are following a similar approach, involving the community and taking feedback into account for current and upcoming projects. The main difference is that they’re splitting development into multiple games, rather than, say, launching Artemis in early access and taking things from there.

Preface: Undiscovered World, which got a tech demo on Dec. 5, is meant to be the first iteration of the studio’s in-house engine, called Melba. Over time, the studio’s goal is to eventually stop using Unreal as a base engine and develop with Melba instead, and then take the systems that were made for previous games into Artemis.

These plans, however, aren’t without trial and error. Greene says that, a year ago, he was worried about Prologue: Go Wayback!, as it wasn’t in a playable state. Now, it’s scheduled for a mid-2025 release, and the feedback gathered from players interacting with the Preface demo is helping inform the game’s development.

Preface is intended to launch the studios own internally developed engine, Melba.

PlayerUnknown Productions

“I had a really strong development team, but I had no one at the top that really could give me a very pragmatic view on how to achieve it, right?,” Greene says. “I had some very smart people, but they were just in the wrong roles. So, about a year and a half ago, I was put in contact with David Polfeldt, ex-Massive Entertainment managing director, and he and myself had some long conversations, and he educated me a bit on that these things are built or how good teams are built and how to best leverage the team we had to achieve what I wanted to do.”

In addition to Polfeldt, who joined PlayerUnknown Productions as senior adviser, Greene hired CEO Kim Nordstrom and CTO (Chief Technology Officer) Laurent Gorga. As Greene explains, they all were instrumental in learning about the long term vision, and coming up with the best course of action to achieve the three-game plan.

“They kind of validated that, which was nice because then I wasn’t crazy anymore,” he says. “I thought, ‘Okay, maybe this is too big, maybe this is nuts.’ But then I have some very senior people in the gaming community saying, ‘No, if you can pull this off, this is great, and I really want to help with this.’”

In order for Melba to be able to create different large-scale planets each time somebody presses play, the engine uses machine learning (ML) technology and Natural Earth data. The first is a subset of Artificial Intelligence (AI) — in essence, ML uses algorithms that learn from data to make predictions. In the case of these games, it’d be the equivalent of asking the engine to build mountains, and the engine knowing, after it was inputted by developers beforehand, how mountains should look, and what biomes and terrains have to surround them. On the other hand, Natural Earth is a public domain map dataset that allows people to make big-scale maps.

The Melba engine will combined developer-fed machine learning and public domain data to quickly chart its maps.

PlayerUnknown Productions

“When I started off, it was just meant to be a big world, right?,” Greene says, “100 by 100 kilometers. And then I found the way to do that. You could create any scale of world, right? Because it’s not [dependent] on humans, you’re creating it using machine learning technology. So, it’s generated rather than created, right? We still use artists to style and sort of shape the world, but the world itself is generated.”

Around the same time, Greene became invested in the idea of the metaverse — a loose term for interconnected virtual worlds, mostly pushed by companies like Meta (formerly Facebook) around technologies like virtual and augmented realities. But Greene didn’t understand the use cases back then, which seemed like a group of IP bubbles that people would eventually link up to somebody. To him, it’s more about a 3D internet, giving people a world engine that they can use and distribute, and that it’s not controlled by one person.

“That’s why Preface is open, so to speak, in that we are allowing people to mod it and mess with the code and it’s not encrypted because that’s what I think the internet started as,” Greene says. “It was just a very basic protocol that people modified and hacked and then created the internet, right? I think ultimately the metaverse has to be an open framework that everyone can access and create their own worlds or visit our worlds or whatever worlds.”

Artemis and its predecessors are intended as a gateway to an open, 3D internet that could take ten to 15 years to reach its potential.

PlayerUnknown Productions

With Melba, the team is trying to find a way for the world generation to happen locally on somebody’s PC, rather than relying on servers elsewhere. The obstacle is making it so a large influx of players is able to access said worlds, rather than player bubbles who have really good internet bandwidth. Greene is envisioning this to take “ten years, probably 15,” with the ultimate goal being a state in which Melba can build digital places easily and open for people to use. “I want hundreds of thousands. I want millions of players though in a place together, experiencing a concert or whatever and a server client is never going to achieve that,” he says.

Conversations about the metaverse and blockchain usually go hand in hand. In 2022, developer Mojang Studios says that it wouldn’t be allowing NFTs or blockchain technologies in Minecraft. That same year, in an interview with Hit Points, Greene spoke about blockchain in regards to Artemis being a digital space that needs to have an economy. “I do believe you should be able to extract value from a digital space,” he said. Some outlets that picked up the news said that Artemis would be featuring the aforementioned technologies. Two years later, when asked for confirmation if Artemis will indeed have NFTs, Greene responded in a similarly ambiguous manner, considering the 15-year-long journey.

“No, oh no,” Greene laughs. “I was asked my opinion on blockchain and then the next day it was like, ‘PUBG guy making a blockchain game.’ And I was like, ‘That’s a no.’ Yeah, I happened to mention blockchain but what I mentioned was like, as a financial instrument or a financial layer within a digital space, it’s an interesting piece of tech.”

By opening up the code for Artemis, Greene hopes users will help develop it organically like the internet in the Nineties.

PlayerUnknown Productions

Greene continues: “Whether it’s the current iteration or something in the future, I have no idea, but it’s a digital ledger and that’s useful. And that was a point that like, I haven’t even thought about NFTs or that kind of, like adding that, like for me that’s a tool that can be used later to do some stuff. But really, it’s not a concern right now because we need the world and we need it working and we need people interacting and we need, you know, all this. We even need to prove marketplaces and all these kinds of layers you have to add to a digital place. So it’s, yeah, it takes time but you know, we have time to spend on it. So that’s where that came from.”

Not trying to reinvent the survival genre wheel

The concept of Prologue: Go Wayback! is simple: a player needs to get from point A to B, interacting with a weather station to ask for their rescue. Maps are eight by eight kilometers big, and the obstacles are related to weather. If it rains, surfaces will become slippery and rivers will go up, for example. This made sense for the team, considering the goal behind Prologue is to be a test bed for the terrain system that will eventually be iterated on for Artemis.

Using its machine learning base, Prologue can retain a relatively small team of developers.

PlayerUnknown Productions

“We’re not building a team of 120 people to finish the game,” Greene says. “The Prologue team is quite small. It’s about 30 people. So, we’re really trying to keep the numbers down because that’s what we’re trying to solve here, making worlds without building huge teams.”

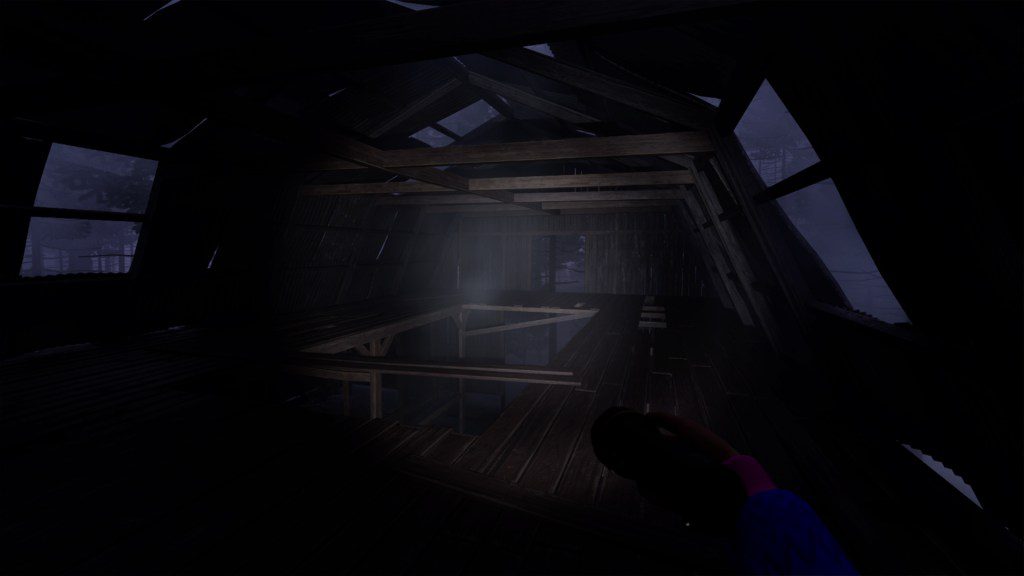

Greene says he doesn’t play a lot of survival games, and he’s more interested in emergent gameplay in general, with players facing a procedurally generated world where you don’t know what sort of hostile obstacles you’ll encounter. “The game will be tough enough and it might be a boring walking simulator,” he says. “But for me, the aim here is to test the terrain and see if we can really generate millions of interactive maps and millions of maps that are playable, right? That gives the player that unique experience every time.”

When asked about whether the team was attempting to bring new ideas to the survival genre, which has been popular to the point of being overcrowded, Greene reaffirms the main goal of proving that Prologue can provide a fun journey using simple mechanics rather than reinventing the wheel.

For now, the games aren’t intended to reinvent survival systems, but be familiar while the world-building tech does the innovating.

PlayerUnknown Productions

“We’re reinventing how you create the terrain, sure,” he says. “But the other mechanics are kind of, you know, we stand on the shoulder of giants as they say, like this has been done a lot before and we’re not going to try to redo it here because it’s not the point of why we’re doing Prologue.”

Looking ahead to Prologue‘s release in 2025, the community’s involvement around the Preface: Undiscovered World demo is giving Greene hope that some people are invested in the long term plan. “I don’t know how cool it can be and I don’t know what we can do with it,” he says, “but we need a lot of opinions here because us deciding everything is just not the right way.”

“And I think it’s not the right way to build, well, the internet or the metaverse either, you don’t build it with, you know, your vision,” he adds. “You have to accommodate so many voices because the world is a huge diverse place. So, building something that’s ethical and fair and works for everyone takes time and takes all the voices. So, we start with Prologue, we start small, we have a small community and we just keep growing. And I think as long as we have the support to do it, then we’ll be good.”