Musk Admits He Doesn’t Fact-Check Himself and Has Two Burner Accounts on Twitter

Elon Musk‘s erratic posting on X, formerly Twitter, has come back to haunt him once again as a 22-year-old Jewish man pursues a defamation case over tweets in which the tech mogul baselessly suggested the recent college graduate was an undercover federal agent posing as a neo-Nazi during a street fight between far-right groups. Musk’s excruciating March 27 deposition in the matter, which a judge ordered released to the public over the objections of the CEO’s lawyer, reveals the extent to which he has continually sabotaged both himself and the social media platform he owns.

X is “the most accurate, timely and truthful place on the internet,” Musk said during his questioning about a false statement he made on the site that has been viewed by over a million users and has yet to be retracted or deleted almost a year later.

The lawsuit, brought in October by Ben Brody of California, concerns one of the many false conspiracy theories that Musk has fallen for and amplified since acquiring Twitter. Last June, as members of the fascist Proud Boys gang brawled with the Rose City Nationalists, a neo-Nazi organization of the Pacific Northwest, at an LGBTQ pride event that both sought to disrupt, several RCN participants were unmasked. Internet sleuths went to work matching names to their faces, but far-right accounts hoping to frame the violence as a “false flag” event incorrectly identified Brody as one participant, circulating a picture of him from the Instagram account of Alpha Epsilon Pi, the Jewish fraternity to which he belonged as a student at the University of Riverside, California. In fact, Brody had been in California at the time, and this misinformation was based on nothing more than the slightest resemblance between Brody and the individual at the event.

The Instagram post described Brody as a political science major who wanted to work in government after graduation, details that extremists used to implicate him in a supposed plot by federal agencies to stage a violent clash between hard-right groups. Twice, Musk boosted those misleading claims, in one case replying “Always remove their masks” to a crypto influencer who accused federal agencies of “Planting Fake Nazis at Rallies.” Finally, Musk replied to an anonymous blogger who posted about a “white supremacist unmasked as suspected fed,” writing, “Looks like one is a college student (who wants to join the govt) and another is maybe an Antifa member, but nonetheless a probable false flag situation.”

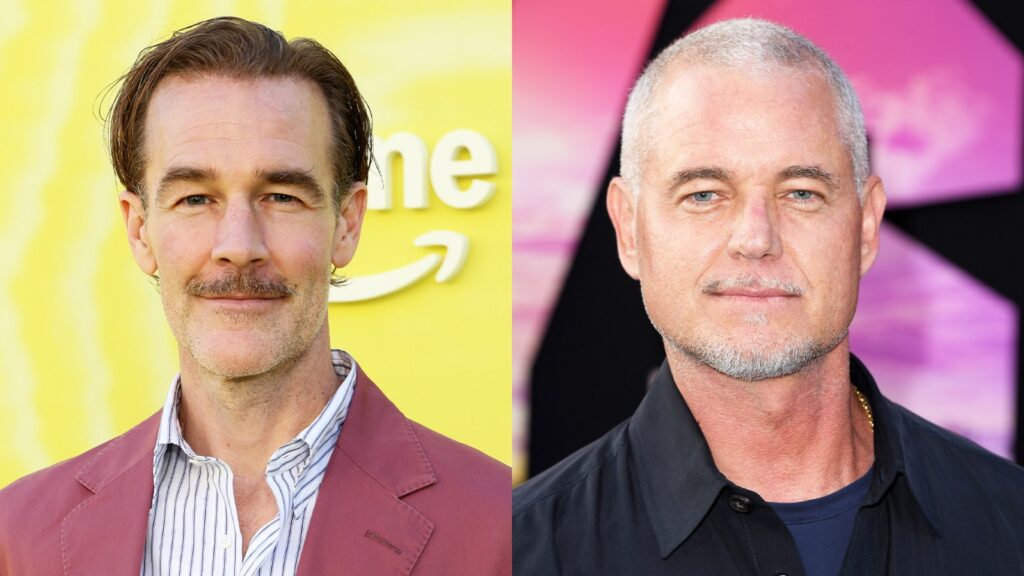

Brody’s attorney, Mark Bankston, who previously won Sandy Hook parents $45 million in damages from Alex Jones in a suit over the conspiracy kingpin’s false claims that the deadly school shooting never happened, has argued that Musk defamed Brody in this last post, with the college grad and his family doxxed and harassed to the point where they were forced to flee their home.

Cross-examining Musk about his social media habits last month, Bankston got into testy exchanges with both the billionaire’s attorney, Alex Spiro, as well as Musk himself, who complained that Bankston lacked “decorum.” (Spiro successfully defended Musk in a previous defamation case over a tweet in which he had insulted a British cave diver by calling him a “pedo guy” during efforts to rescue a Thai youth soccer team trapped in a flooded cave system.) Despite his defenses, Musk was backed into several embarrassing statements, and commented early on that he had “a limited understanding” of “what the lawsuit is about.”

Musk was reluctant to even acknowledge that Brody had brought the lawsuit — he more than once commented that Bankston was the true plaintiff and interested in “getting a lot of money.” Bankston, however, pushed through to the subject of the suit itself, getting Musk to confirm that he had not done anything to independently verify the identity of the RCN member misidentified as Brody before his allegedly defamatory tweet. Asked if had secured “other information about this unmasked brawler” besides what he’d seen from the handful of extremist accounts pushing the false flag conspiracy theory, Musk replied, “I don’t recall securing other information.” He also granted the point that everything he supposedly knew about the brawler came from those tweets.

Bankston further pushed Musk on his dubious sources, asking if he clicks through to profiles and feeds to scan for “red flags” when it comes to reliability. “I wasn’t trying to assess their credibility,” Musk said of one account he engaged with, which Bankston pointed out had posted antisemitic content the same day it shared the Brody conspiracy theory. Musk contended that even if he’d been aware of such a troubling agenda from the user he had relied on for information, he couldn’t automatically discount their views. “You know, like, once in a while, a conspiracy theorist is going to be right,” he told Bankston.

Elsewhere in the deposition, Musk criticized the mainstream media and “so-called misinformation experts” and insisted that X has better ways of ensuring accuracy. In particular, he praised the platform’s Community Notes feature as “the best system on the internet” when it comes to fact-checking. Yet Musk has at times taken issue with Community Notes on his own tweets, and, though he tagged Community Notes in his post endorsing the erroneous “false flag” claims about the Oregon melee, the post has never received a correction. Musk conceded that there’s always “some risk that what I say is incorrect,” but said this had to be balanced against “a chilling effect on free speech in general, which would undermine the entire foundation of our democracy.”

At times, Musk was forced to wrestle with his own reckless actions as the owner and prime influencer of X. “I may have done more to financially impair the company than to help it,” he told Bankston in one exchange, adding, “I do not guide my posts by what is financially beneficial but what I believe is interesting or important or entertaining to the public.”

Musk confirmed, too, that one exhibit entered into court records showed another account he operated for “test” purposes. The profile, @Ermnmusk, came to light a year ago as a probable secret Musk account because he tweeted an image showing himself logged into it, and Motherboard then reported on a number of indications that it was likely his. Some since-deleted @Ermnmusk tweets appear to show Musk posting in character as X Æ A-12, his toddler son with singer Grimes, announcing his fourth birthday or saying, “I wish I was old enough to go to nightclubs. They sound so fun.” Other tweets were more risqué, including one that asked: “Do you like Japanese girls?” Musk revived the account on the day of the deposition, writing, “I’m back,” and proceeded to post several memes and jokes in the following days.

Musk dropped the name of a second burner account as well, though it may have been recorded incorrectly in the transcript of the deposition, which has it as “baby smoke 9,000.” There is no active X profile with that handle, though a verified account called @babysmurf9000 interacts with many of the same accounts that Musk follows and engages with, retweets official X company accounts, and posts in an emoji-laden style similar to Musk’s. It can also be found disparaging billionaire Mark Cuban, whom Musk has routinely criticized of late, as “an idiot.” That post came as Musk feuded with Cuban via his main account over DEI programs in early January.

Other strange revelations in the interview included Musk’s claims that he was unaware of Brody seeking a retraction of the false flag posts in order to clear his name (at the time, the college grad had made a viral Instagram video refuting the conspiracy theory and asking for people to leave his family alone), that what he tweets out to millions of followers isn’t always seen by that many people, and that he doesn’t believe Brody “has been meaningfully harmed by this,” because it is “rare” for media attacks to have “a meaningful negative impact” on their targets.

Those comments sometimes drew incredulous responses from Bankston, who said “Wow” when Musk said Brody hadn’t been harmed by his false tweets about him. After Bankston made some inquiries into whether Musk felt he had been reckless or failed to take responsibility for his actions, Bankston and Spiro argued more about the scope of the questioning before concluding the proceeding with a debate as to whether the transcript would be made confidential by a protective order. Bankston stated for the record that in his opinion, Spiro had conducted himself inappropriately and “completely shut down many segments of the deposition.”

As for the protective order to seal the transcript, Bankston said he would wait to hear from the court, but that “we don’t recognize that request as anything valid.” Clearly, neither did the court.