Meet the Nigerian Creators Going Global

I

n June, Nigerian comedian Isaac Olayiwola — known as Layi Wasabi on TikTok and Instagram, where he has more than 3 million combined followers — took his first trip to London. There, he had his beloved skit character “the Law” endure U.K. hijinks as if it was his first time as well. In one skit, the Law — a soft spoken but mischievous lawyer who can’t afford an office — bumps into a local, played by British-Congolese creator Benzo The1st. In sitcom fashion, the Law breaks the fourth wall to wave at an invisible but audible studio audience as Benzo watches on, confused and offended. In another, Olayiwola links with longtime internet comedy creator and British-Nigerian actor Tolu Ogunmefun to have the Law intervene in the relationship of a wannabe gangster and his fed up girlfriend. In another, he goes to therapy complaining that he can’t find clients in London (“Everything seems to work here in the U.K.”).

Olayiwola wasn’t in London just to film content — it was a reconnaissance mission, too, sitting for interviews and testing stand-up sets to see how his humor might translate. After breaking out as one of Lagos’ most popular creators, he’s set on becoming a top comic — not just in his region, but in the world.

He’s not the only Nigerian comedy creator to have captivated the regional market — of the roughly 218 million people in the country, 70 percent are under 30, and local brands are often eager to give social media stars ad deals. Some of these creators say they want to expand their audiences and profitability and are looking elsewhere to do it. They tell Rolling Stone they want to be the kind of megastars that they’ve grown up watching, like Eddie Murphy, Kevin Hart, and Ellen DeGeneres. But instead of assimilating to Western tastes, these creators are keeping their Nigerian communities and culture front of mind — and finding success.

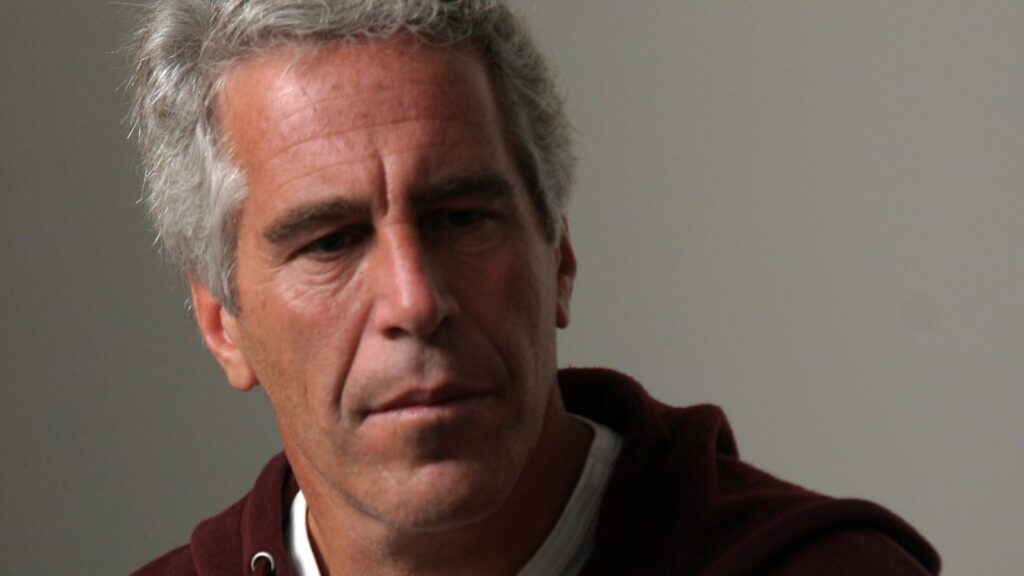

Layi Wasabi

Morgan Otagburuagu

“My latest hobby is making money,” jokes Eniola Olanrewaju, known as Korty EO on YouTube, where she has more than 300,000 subscribers. Her content varies — in her docuseries Flow With Korty, she spends time with Afrobeats artists like Rema and Ayra Starr, while on her show Love or Lies, she sets real singles up on blind dates. Her content is cinematic, emotional, and comedic, and looks into the lives of people she thinks are misunderstood, like when the famously reserved singer Tems opened up to her about having never been in love. “Love is when you see the person — the person’s yansh [Pidgin for buttocks] is open and you’re like ‘I still want it,’” Tems said earnestly. Korty thinks that kind of work transcends place.

“I can do that across the globe and it’ll connect with every single person,” Korty says. “But my roots still remain Nigerian.” Part of her motivation to widen her reach is to build more pathways for Nigerian creatives to tell stories of their communities. “We’re very industrious and ambitious people, but there’s also a lot of poverty here,” she says. “That’s the importance of collaborations with other people on other continents — it just brings more eyes to the beauty happening [here].”

Olufemi Oguntamu is working to build pathways, too. Oguntamu — who goes by Penzaar, a nickname he inherited from his father — was actually a proto-influencer himself, able to rally his entire college campus with a text back in the days of BlackBerry Messenger. He went on to build an agency that has helped about 20 African creators navigate brand deals, cultivate engagement, and structure their content, he says. He’s observed that fashion, tech, and food videos are doing well in Nigeria, but none as well as comedy. While people may just bookmark a great get-ready-with-me or recipe demo, if something makes them laugh, they share it. “With comedy, you tend to become popular faster,” says Oguntamu.

Isaac Olayiwola is one of Oguntamu’s clients. As Layi Wasabi, with his lanky frame and broad smile, Olayiwola has one of the most recognizable faces on the young Nigerian internet. “Layi is extremely ingenious,” says Ibukun Filani, who earned his Ph.D. in linguistics at the University of Ibadan studying African comedy. In Pan-African folktales, tricksters have always been an important archetype, Filani explains. They reflect hope and resourcefulness in harsh conditions. Olayiwola has played into that. “What sells Layi is him reflecting what Nigerian life actually is,” says Filani “[His] lawyer is poorly paid, and goes from court to court to get people to bill so [he] can make some money.” Another one of Olayiwola’s characters, Mr. Richard, goes around town promoting a get-rich-quick scheme on WhatsApp with slick words and finesse.

Taaooma, née Maryam Apaokagi, another popular online comic, parodies Nigerian gender roles and social norms while playing every member of a raucous family. Filani compares Apaokagi’s work to Tyler Perry’s. “You might just find the Madea image in Taaooma in some of her skits where she’s the mother. Then, she also represents the struggles of a girl growing up under [that mother’s] strict supervision, who doesn’t have [freedom].” Apaokagi wants to make movies, she says, and “definitely” wants a Western audience. She believes she can stay true to herself to get it. “There’s something that they say — if you want to win the whole world, at least win your community first,” she recalls. “When you stretch your hands out to other places, your community’s going to support you. So, that’s what I’ve tried to do.”