Inside the WWE Writers Room, ‘A Kingdom Ruled by Fear’

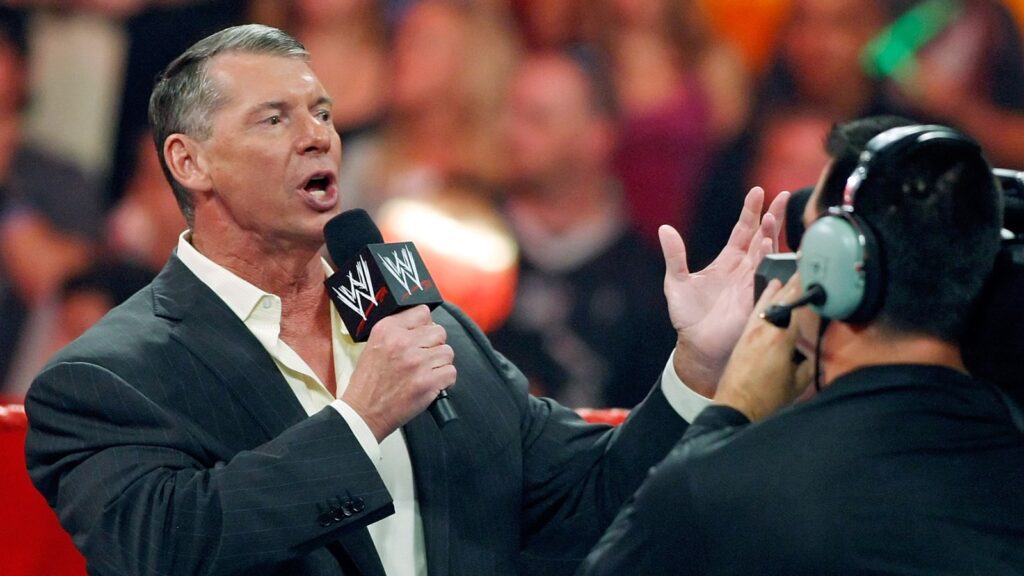

When Michael Leonardi was fired from his job as a television writer at the WWE in 2016, he says he was told by an HR representative and the head writer at the time that he was “not fit for the role” — this despite, according to Leonardi, him getting a promotion, a raise, and positive feedback during his 10-month stint. But less than a week prior to his dismissal, Leonardi says, he was dressed down by the company’s then-CEO Vince McMahon for making a last-minute, minor change to a script that he and other wrestlers thought was racially insensitive.

“He turned to me and he said, ‘So you didn’t give me what I wanted?’” Leonardi tells Rolling Stone. “I said, ‘I understand, I’m sorry. We all went over it and felt good about it, we just made the small tweak.’ And then he started just yelling at me. It was such an intense moment. I walked out with my tail between my legs.”

Leonardi is one of six former WWE writers who spoke to Rolling Stone about what they describe as a hostile environment in the TV writers room, which they say started at the top with McMahon and was perpetuated by staffers in leadership positions there. The majority of the former writers, who worked on the network’s long-running shows Monday Night RAW and SmackDown! for anywhere from four months to five years, between 2016 and 2022, asked to remain anonymous out of a fear of retribution from the WWE, their former colleagues, and rabid wrestling fans.

“WWE is a kingdom ruled by fear,” one former writer tells Rolling Stone. “It is the motivating factor everywhere: fear.”

Representatives for the WWE did not respond to multiple requests for comment on this story. In a statement, a spokesperson for McMahon told Rolling Stone, in part, “Scores of writers could share tales of what an enjoyable, creative and freewheeling environment the WWE writers rooms were. This handful of (obviously disgruntled) individuals aren’t representative in any way of the consensus — or of the truth.”

THE WORKPLACE CULTURE of the WWE (and the WWF before it) has been rife with alleged misconduct for decades. As far back as the late Eighties and early Nineties, there were accounts of rampant drug and steroid use among wrestlers, as well as claims of sexual harassment and abuse of both men and women within the organization. (Neither McMahon nor the WWE responded to requests for comment on these incidents.) All the while, as described in the new Netflix docuseries Mr. McMahon, McMahon seemed to thrive on the controversy, and the organization grew.

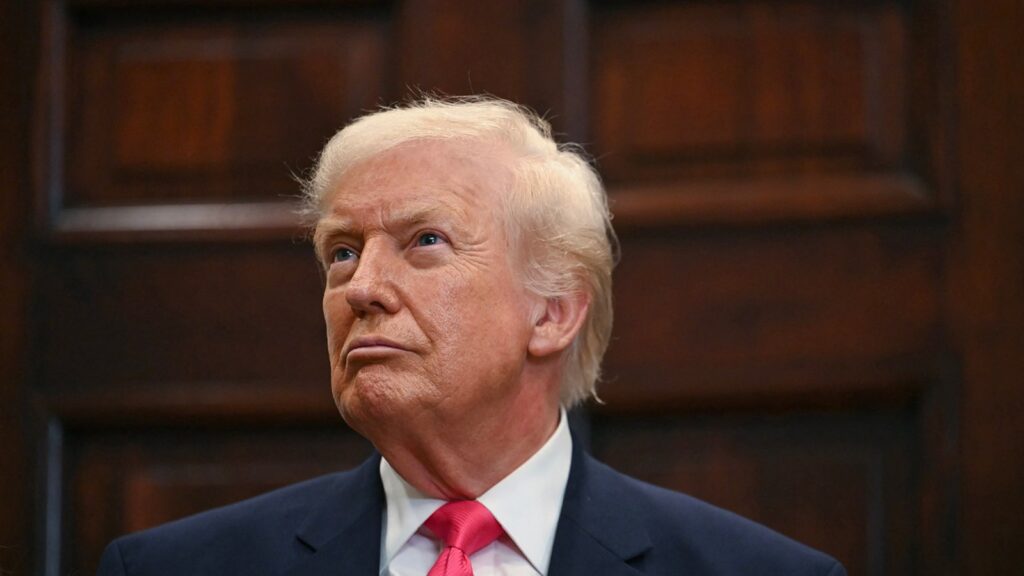

But in recent years, claims against the company and McMahon personally have reached a crescendo. In 2022, he stepped down as WWE CEO following a Wall Street Journal report that alleged he paid more than $12 million to four women to silence them from speaking out about instances of sexual misconduct and extramarital affairs he’d had with employees. Then, in January, a former WWE employee, Janel Grant, filed a lawsuit accusing McMahon of sexual assault and sex trafficking, saying he pressured her into having sex with him and another WWE staffer in exchange for her job. The day after the suit was filed, McMahon resigned from his role as executive chairman of TKO Group Holdings, the conglomerate born from the 2023 merger of WWE and UFC, as well as his position on its board of directors. (In a statement at the time, McMahon denied wrongdoing, calling Grant’s lawsuit “baseless” and “replete with lies.”) He is currently under federal investigation in connection with Grant’s claims.

McMahon, who purchased the WWE (then known as WWF) from his father in 1982, crafted a villainous public persona starting around the mid-Nineties, often appearing on the organization’s shows to snarl at various wrestlers and even competing in the ring. In 2002, he instituted what he called the organization’s “Ruthless Aggression” era. But the writers who spoke with Rolling Stone say McMahon’s intimidating behavior was not just for show. By berating and belittling those around him, they say, he instilled a culture of fear that trickled down.

“There was a very heavy layer of fear and tension and that was directly from Vince,” Leonardi says. “And that culture that he created obviously created a lot of problems.”

The six writers who used to work at WWE tell Rolling Stone they regularly witnessed or were on the receiving end of verbal abuse. The allegedly hostile conditions permeated not just the writers room but the company in general, they say, whether at the corporate headquarters in Stamford, Connecticut, or when the organization’s TV shows filmed on the road. The former writers say staffers seemed to be divided into two camps: those who were WWE loyalists and only had experience working at McMahon’s company, and newcomers with outside experience in the entertainment industry who immediately realized the WWE was unlike any other workplace they’d seen.

“Everybody was getting yelled at all the time in the room,” one former writer says. “It was more saying shit that was humiliating or mean [that was then] couched as a joke, but it’s a nasty joke.” The writer adds, “If you’re being targeted in the room, nobody stands up for you, but that’s because if they do, they will get the bullet in the head, too. You don’t stick your head up out of the foxhole for anybody, because nobody wants to take a bullet.”

LEONARDI WAS ORIGINALLY hired to work at the WWE as an associate producer in 2001. He says he quit the job in 2005 because he had been demoted and stripped of his responsibilities after telling his superiors he was uncomfortable working on a storyline he viewed as insensitive. Days before the July 7, 2005, London bombings, in which Islamic terrorists detonated explosives on three city commuter trains and a bus, the WWE had scripted a SmackDown! segment in which the controversial character Muhammad Hassan defeated the Undertaker with the help of five men dressed in ski masks, black shirts, and camo pants. The episode aired as planned on the 7th, with a parental advisory. Still, many viewers found it offensive. Even though the WWE later eliminated Hassan’s character due to outside pressures, and Leonardi says he was eventually given his responsibilities back, the former writer says he couldn’t get past his experience of allegedly being punished for speaking up.

A decade later, Leonardi reconsidered his stance on the company when he saw a writing position open up. A longtime wrestling fan, it was his dream job to be a writer there, so he applied and was hired back at WWE, this time to work in the writers room. But not long after, he says, another troubling storyline arose. During the taping of a Monday Night RAW segment that aired on Martin Luther King Jr. Day in 2016, Leonardi says he was producing on the road with wrestlers, R-Truth, Titus O’Neil, and Mark Henry, all three of whom are Black, and Neville, who is white. As Leondari described in a video he posted to LinkedIn this past February, “The script called for Neville to speak up and tell everyone else that he’s ‘got a dream too, and that dream is to win the Royal Rumble,’” referencing the civil rights leader’s historic 1963 speech at the Lincoln Memorial. Leonardi says Neville told him he was uncomfortable delivering the line and, with a limited amount of time, the bit was changed so that R-Truth said the line instead. Leonardi says his boss at the time, Dave Kapoor, approved the change. (Kapoor could not be reached for comment. Neville and R-Truth did not respond to requests for comment.)

According to Leonardi, there were many other times when segments weren’t executed verbatim, with the talent going slightly off script. Sometimes wrestlers would even ad lib a little, he says, and “it was not a big deal.” But after bringing the change to McMahon’s attention, he says, the boss became furious. Following their confrontation, Leonardi was let go.

A spokesperson for McMahon denied Leonardi’s account in a statement. The spokesperson acknowledged that McMahon had “an extremely hands-on approach” with WWE scripts, adding, “That’s why the idea of him suggesting or approving the use of a famous Martin Luther King, Jr. quote for a punchline to be used by a white British character is so ridiculous. It simply didn’t happen.”

This wasn’t the only alleged instance of racial insensitivity in the WWE writers room. In 2023, former WWE writer Britney Abrahams filed a lawsuit against the company and specific executives, including McMahon, alleging she was fired in 2022 after she pushed back against racism she experienced in the writers room. According to court documents, Abrahams, a Black woman, says she openly disagreed with storylines she felt played to racist stereotypes. She also says she was fired because she took a commemorative chair from a WrestleMania event, despite white employees having done so in the past without punishment. The lawsuit was later dismissed, and Abrahams’ attorney, Derek Sells, told a Wrestlenomics reporter the matter was “resolved amicably.”

ACCORDING TO THE former WWE writers who spoke to Rolling Stone, the TV writers room was unlike any other they’d experienced. For one thing, the fact that McMahon himself — the CEO of a company of more than 800 people — regularly joined and supervised the small staff of writers (around 20 to 25 people, depending whether a show was being produced at headquarters or on the road) was highly unusual. There were also unconventional rules, including a formal dress code. In a document detailing the dress code obtained by Rolling Stone, the company required men to wear suits and women to wear skirts, dresses, or pantsuits; in addition, all employees were instructed to keep their shoes shined at all times. There were other policies the former writers say were atypical compared to entertainment industry standards: The writers allege they were told not to sneeze in front of McMahon because he saw it as a sign of weakness and to always push their chairs in when they get up from a table. The writers say they were also instructed to stand whenever McMahon walked into the room and to sit down only after he took his own seat.

“Many of the anonymous writers’ claims bear no resemblance to the reality of the writers room,” a spokesperson for McMahon said in a statement. “Vince never told people to stand up when he entered the room. That’s ludicrous.” (The former writers who spoke with Rolling Stone say that while they did not hear the directive from McMahon himself, they were instructed by their managers to follow this rule.)

Most unorthodox of all was McMahon’s direct say in the final scripts, the writers say. Until he stepped down as CEO and chairman of the company two years ago, McMahon was closely involved in every single script. The former writers describe a process that was hardly collaborative: Writers would pitch story ideas to lower-level supervisors and head writers, and, on days McMahon was in the room, directly to him. They would sometimes produce multiple versions of scripts. But ultimately, they say, McMahon changed storylines — even ones he’d previously approved — and entire scripts on the day of the taping. He “destroyed everything by the time we got to air” seemingly just to exert his dominance, one former writer says.

“It doesn’t really matter what he said in that creative room or if he loved it [at an earlier point], it was still going to get torn up before the show,” one former writer says. “By the time Monday rolled around and we were all in the production meeting, something else was gonna happen. It almost felt like a joke, like we were just there to satisfy Vince’s whims. We were all Vince McMahon transcribers.” The writer adds that there was something about McMahon’s changing directives that felt almost sadistic: “I think Vince enjoyed the manipulation. He liked changing things. He liked keeping people on their toes. I genuinely felt like, this isn’t to benefit the show or the storyline, Vince really just enjoys making people squirm.”

Writers say it was commonplace to wait around the Stamford office late into the night for McMahon to show up to their scheduled meetings about that week’s scripts. One former writer says they would often wait “for hours, and you wouldn’t know why you were waiting.” The writers claim meetings sometimes did not start until midnight and didn’t wrap until 2:00, 3:00, or 4:00 in the morning.

In a statement, a spokesperson for McMahon said: “Like many jobs in the sports and entertainment industries, the writer’s position was not a 9-to-5 gig. If new ideas needed to be implemented or changes made to the script, meetings could be held late into the evening because of Vince’s availability given his travel schedule and his multiple duties at the company as CEO as well as overseeing all of the creative content for hundreds of live events and broadcasts every year.”

It wasn’t just McMahon who was the problem, the former writers say. One former writer says that while they didn’t have any negative experiences with McMahon directly, they thought other writers in the room who were in positions of power could be “bullies,” motivated by fear of upsetting McMahon and losing their jobs. Those who demonstrated this type of loyalty to McMahon tended to be avid fans of wrestling who had spent their careers inside the world of WWE, the writers say.

“Those people were the most miserable people I’ve ever worked with, but that’s where a lot of them had worked their whole professional lives and that’s the only game in town,” one writer says. “They didn’t know what it was like working on a regular television show.”

One former writer claims they witnessed a colleague in a leadership position tell another writer “something to the extent of, ‘I wish your dad pulled out and came on your mom’s tits instead of having you.’”

“This was, like, good old boys locker-room talk,” the former writer says. The more someone was promoted and the closer they got to “that innermost circle,” the writer adds, “the more volatile it got, and the more you dealt with some of these ‘good old boys.’”

The jockeying for favor with McMahon turned people against each other, the former writers say. One compares the WWE writers room culture to a “Mafia style” of leadership in which “if you do one thing , you’re pissing off three other people who are higher up than you who are going to chew you out, get angry, or seek revenge.”

“I couldn’t understand what the hell was going on because nobody made eye contact, nobody talked to you. It was so odd,” another former writer says. “Everybody’s scared and the only laughs are at someone else’s expense…. Everybody is emotionally shut down because of the verbal beating that they take and the humiliation. That’s what the room is like with a bad leader.”

WOMEN IN THE WWE writers room faced specific challenges. Of the former writers who spoke with Rolling Stone, the women say they felt othered and became hyper-aware of their gender because of how they were treated by male writers. One former writer says people would comment on her outfits and touch her in ways that felt unnecessary; even though the behaviors weren’t explicitly sexual, she says it felt like a means of controlling her in a way that didn’t happen to the men in the writers room.

“They would touch me where they would have me come closer [to them],” she claims. “They would pull me by my waist to come somewhere or move closer to them. I’m just super aware that it’s kind of close to my butt and most people don’t touch me by the waist ever. I thought, ‘This is strange.’”

Two former writers tell Rolling Stone they took their complaints to human resources. One was subsequently fired from her position, a decision she interpreted as retaliation. According to former writers, enough female writers complained about their treatment to WWE HR in 2020 that leadership held a Zoom meeting they referred to as a “women’s forum,” in which the affected writers were encouraged to collectively air their grievances. One former writer says she grew emotional when she told everyone in the meeting that she didn’t feel safe with her co-workers. Another woman who attended the meeting says the leadership staffers there were dismissive of the womens’ claims. “They did it just to appease us, but they didn’t take it seriously at all,” she says.

After the Zoom meeting, the writers who spoke with Rolling Stone say, there was an in-person meeting with the entire writers room in which senior leadership allegedly told everyone they were “acting like middle schoolers” and not to go to HR if they have any future problems.

One male senior staffer “essentially said, ‘Come to me if you have a problem,’” one former writer alleges, “which is such bullshit, because he’s part of the problem, too. He enabled Vince with everything that he did.”

One former writer who says they have a history dealing with anxiety also says their mental health was impacted by their time working at WWE. They say they were allegedly driven to having “crippling” panic attacks because of the job. When the former employee brought those concerns to a WWE HR representative, they say no one ever followed up or took any course of action.

“When I spoke to HR, I said, ‘I have anxiety. I can’t handle this. This is going to kill me,’” the writer says. “They didn’t care.”

Another former writer says she left the job because she didn’t feel safe working at the company as a woman. The writer says she was uncomfortable with the way other writers would talk about the female wrestlers’ bodies and wardrobes, and how they would mock or make fun of the wrestlers “if they weren’t over-sexualizing themselves.”

“On the one hand, this is the product in the story,” the writer acknowledges, “but on the other hand, I feel like we’re not talking about the story anymore. The undertones are dangerous, and what they wanted in their environment scared me.”

The writer says the way that male writers spoke about and treated other women, including the network’s female WWE Superstars, made her feel like “an object.” “I felt like there’s no way I could be in this boys club,” she says.

DESPITE THE ALLEGED toxicity of the writers room, Leonardi says there were also times he felt a degree of camaraderie with his colleagues because they were “all in this together, getting shit on all the time.”

“When Vince wasn’t there, it was amazing to see how things opened up,” he says, describing the mood as “jovial” on occasion. “People start talking, the creativity [flows]. It’s just so clear how much his influence and the way he ran things would actually stifle the process.”

The six former writers who spoke to Rolling Stone say they have no direct knowledge of or insight into the sexual assault and trafficking allegations against McMahon, but they were not necessarily surprised to learn about Grant’s lawsuit. Not only were they aware of past allegations made against the former CEO, but the writers say rumors floated around the office about McMahon and other women who worked for WWE.

“I never saw anything crazy like that,” one former writer says. “Certainly while I was there, I heard some of the other writers joking, like, ‘Yeah, there’s some women that work in this company that nobody knows what they do.’” When allegations of hush payments by McMahon emerged, the writer says they didn’t find it “off brand for the Vince that I knew.” (In response to the Wall Street Journal’s 2022 report about hush-money payments, a WWE spokesperson told the outlet that the company was “cooperating with [a] board inquiry into the matter…and taking the allegations seriously.”)

Another former writer says they weren’t “shocked, but it doesn’t mean that I still wasn’t sickened by it.” The writer adds that reading the details of Grant’s allegations “finally allowed me the freedom to say, ‘That place was fucked up.’”

There’s more than one side to McMahon, Leonardi points out. He says there’s no denying that McMahon’s company “has done wonderful things” and the former CEO has “taken care of so many people” over the course of his tenure, especially by creating so many jobs. But McMahon’s business acumen and any acts of kindness he extended toward employees he favored don’t absolve him of the alleged wrongdoing that went on behind the scenes, Leonardi says.

“Multiple truths are present here. We have to acknowledge and recognize the fact that he’s done so many amazing, selfless things for people in the business, for a lot of people that have proven to him that they are loyal or they’re just good workers,” Leonardi says. “But there’s the other side [of him].”

Former WWE head writer Brian Gewirtz, who’s now the senior vice president of development at Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson’s Seven Bucks Productions, published a memoir in August 2022 detailing his experience working under McMahon, titled There’s Just One Problem…: True Tales from the Former, One-Time, 7th Most Powerful Person in WWE. Gewirtz, who also appears in Netflix’s McMahon docuseries, shares a range of stories about his time at WWE in the book, some of them portraying his position in a positive light and others corroborating the experiences of the six writers who spoke to Rolling Stone. In the book, Gewirtz describes the volatile culture of the WWE, how writers were “either there for a minute or a lifetime.” He writes about “bracing” himself “to get chewed out,” addresses incidents when McMahon screamed and yelled at other staffers, and makes statements like, “Vince is the entire company.” (Gerwitz could not be reached for comment on this story.)

After decades of McMahon’s reign, it’s a new era for the WWE. McMahon’s son-in-law Paul Levesque, also known in the wrestling world by his stage name Triple H, is now the company’s Chief Content Officer. Some of the former writers who spoke with Rolling Stone believe that with McMahon gone, the WWE is moving on. Leonardi says he’s heard the work culture has improved and people are “much happier,” calling Triple H “a great leader.”

But other former writers who spoke to Rolling Stone aren’t convinced there will be any major shifts in the overall culture at WWE. The longstanding atmosphere of tension and fear in the WWE writers room is something they don’t have faith can be undone overnight.

“There are a lot of people complicit in continuing this culture,” one former writer says. “I am highly doubtful it’s changed, even with Triple H in charge. I just don’t think it really can.”