‘I’m an Internet Bitch’: How TikTok Created a New Kind of Comedy Career

W

hen Morgan Jay was cast on a prime-time TV show, he thought he’d finally gotten his big break.

A musical comic since 2007, Jay was sure his 2019 multi-episode appearance on NBC’s Bring the Funny would take his career from long nights and low pay to ticket sales and maybe even the hour-long comedy special of his dreams. While singing about the intricacies of modern dating and strumming along on guitar made fans of judges Chrissy Teigen and Kenan Thompson, it didn’t even “move the needle” on his career, says Jay, 37. Then, when the Covid-19 pandemic hit, he started posting clips of his crowd work — ad-libbing with audiences at old shows — and things took off. One clip blew up, Jay says. Then another. Before that, when he opened a 30-seat backyard gig, half the audience was there to see him.

“I never really wanted to be doing social media. First, you had to post on YouTube, then it was Facebook, then Instagram, then TikTok, and then it was ‘You got to be on Clubhouse.’ How many things I gotta do, bro? It was a little daunting,” Jay says. Now, he has 2.8 million followers and is in the midst of a largely sold-out comedy tour across the U.S.

When dance-heavy app TikTok went mainstream during the pandemic, an unintended side effect was an explosion of the app’s comedy landscape. For the first time, starving artists had what they usually fought for tooth and nail: time, money, and energy to create. On a good weekend of stand-up, a comedian might gain 20 new followers from several performances. In comparison, Jay’s following grew by 300,000 basically overnight.

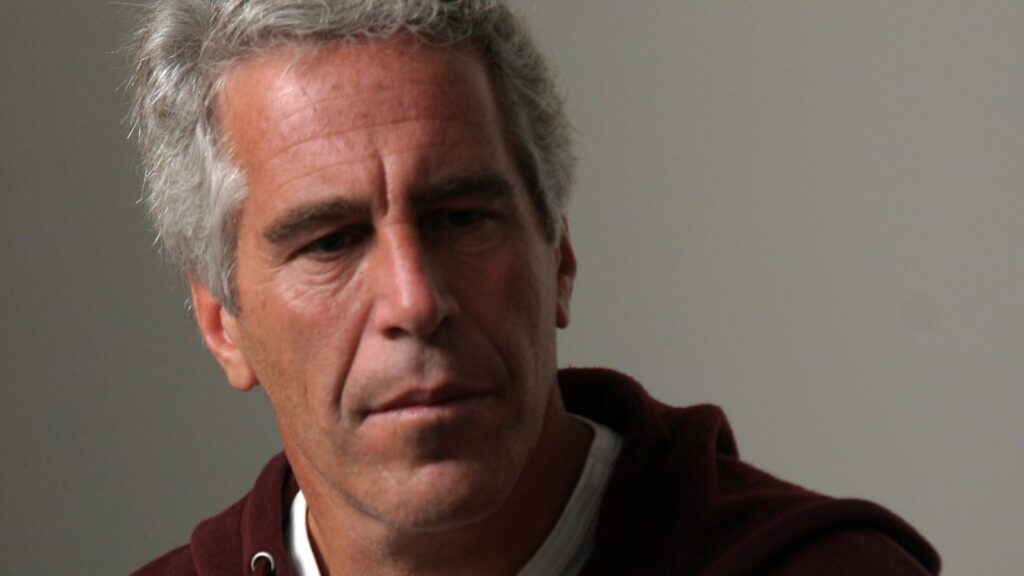

Joseph Buscarello*

Social media has long served as a digital audition ground for mainstream careers — there’d be no Lonely Island or Bo Burnham without YouTube, no Chloe Fineman without Instagram. But with this fresh platform — revolutionary not just for its ease of use, but also its short format and access to massive audiences — a newer question has also emerged: Is a traditional career still what these comics want?

When Kendahl Landreth first watched an episode of I Love Lucy, she knew she wanted to be a comedian. After fan-girling over her high school’s improv team (she calls them “my ‘NSync”), she took classes at the Upright Citizens Brigade, but her character work didn’t bring her stand-up success; it was TikTok audiences who fell in love with her comedic Midwestern sketches. Now, with 2.6 million followers, Landreth still does live shows, but her full-time job is creating content — one, she says, she’s grateful to have.

“It feels like such a wild thing because I was so used to performing for two people at a bar,” says Landreth, 24, who lives in Los Angeles. “I did five improv shows a week, and no one would show up. So to be able to have millions of people watch comedy I make is so bizarre. I’m a very proud content creator.”

“I used to perform for two people at a bar,” says one comic. “To have millions watch is bizarre.”

Even with more comics joining the app every day, TikTok’s reception in comedic institutions hasn’t gone as smoothly as some might hope. Take, for instance, the meteoric rise of comedian Matt Rife, who spun his strong jaw and viral TikTok crowd-work clips into 18 million followers, a Netflix special, and a sold-out world tour. On TikTok, he’s a veritable star, but mainstream comedians like Gary Gulman and Marc Maron have dunked on him (Maron dubbed him “the It boy of shitty comedy”), criticism that often overreaches to denigrate TikTok’s entire comedy scene. For comedy-focused creators, it can mean having to break through preconceived notions about the app before they can be accepted in mainstream places.

Nimay Ndolo doesn’t even call herself a comedian, even though her 2.4 million followers regularly tune in to her TikTok to watch her Gilbert Gottfried-esque, profanity-laden rants about world events, fashion, and sex. But she notes that even though comics who come up through legitimate programs might be more welcomed in the community, the label of creator gives her access to far more revenue streams, including ads, podcasting, and collaborations.

“Are [TikTok comedians] the trash of the public-facing media? I don’t know,” says Ndolo, 29. “But there is a sort of negativity involved with being an internet person.” Stricken by what she calls “quirky Black-girl syndrome,” Ndolo is no stranger to the kind of pushback that influencers can get in comedy spaces, especially when stand-up might not be a creator’s forte. But, she says, that kind of “resistance” can’t stand forever. “I do understand creators wanting to distance themselves from that. But you don’t have to shit on it. Personally, if people ask me, I tell them, ‘I’m out here,’ you know? I’m an internet bitch.” (She has noticed that her humor doesn’t always translate across platforms, like when a recent TikTok about moving to New York went viral on Twitter: “I called my apartment a hellhole, and people said, ‘Oh, no. You called the neighborhood a hellhole!’ And I tried my best to explain, but that just didn’t work.”)

Kenna Sharp*

Not all comics want to spin their TikTok fame into an occupation selling their lifestyle. For Stanzi Potenza, who runs a satirical TikTok page about death, politics, and religion, building a career in comedy in New York sounded fun. Being able to pay for her epilepsy medication even after she lost her mom’s health insurance sounded better. And with 4 million followers on TikTok, being a content creator gave her the financial freedom to pursue stand-up.

“All of a sudden, I went from living at home with my mom in Boston to moving across the country to Los Angeles and financially having access to all these things that I didn’t think was possible,” Potenza tells Rolling Stone. “A lot of people don’t get to become the artists that they want to be because they financially can’t do it. TikTok gave that opportunity to the common person.”

While TikTok comedians are fighting for legitimacy in the comedy world, older institutions are beginning to actively embrace the evolving landscape. The Second City in Chicago — known for churning out alumni like Chris Farley, Tim Meadows, Stephen Colbert, and Amy Poehler — is building out its curriculum to include more instruction on social media platforms like TikTok. Its artistic director, Jen Ellison, tells Rolling Stone that comedy institutions like hers can only stay afloat by “inviting in” the changes apps like TikTok bring to the comedy space.

“[Comedy] is an evolving art form. It responds to the culture that it is in,” Ellison says. “So of course it’s going to find its way into social media. I think that not evolving the curriculum and not evolving towards digital content, TikTok, and any other app that comes down the line is a mistake. We’re still in the process of sort of rebuilding things at Second City.”

And even for comedians who don’t consider themselves only content creators, TikTok can still serve multiple purposes, as both a day job and a connective lifeline. Taking the advice of her therapist, Paige Gallagher used her TikTok account, which at that point had just 40 followers, to overcome writer’s block during the pandemic and work out new material for her stand-up and sketch-comedy group. It netted her more than 1 million followers, new collaborators, and a major career breakthrough. Gallagher attributes the popularity of her content — and other TikTok comedians like her — to people’s desires to open the app and laugh at something everyone has experienced. Not surprisingly, her most popular character is a passive-aggressive mean girl who rules the coop during high school, only to peak before adulthood.

“Relatability, and a little bit of the dark-sided humor, is something that I have always found comforting and funny when I’m seeking out comedy,” Gallagher says. “Shows or movies allow people to feel like they can go into this fantasy world, but TikTok is an amazing place for relatable comedy. I think that’s the biggest thing that it has.”

The connectedness of thousands of people laughing and sharing their own similar experiences has an allure even Gallagher herself isn’t immune to. After the recent death of her boyfriend, her account unexpectedly allowed her to connect with others who were grieving.

Molly Plan*

“I posted a ‘Get Ready With Me to Go to My Boyfriend’s Funeral’ video,” she says. “And I sort of tried to be real, but also be a little bit funny. It’s just the way I cope with things. And the amount of messages that I have gotten since then has been overwhelming. This app [has] created a community that feels real and feels close and genuine. If I didn’t have my online community, my grieving process would have looked a lot different.”

Jay notes that following his TikTok success, he no longer feels a need to reach for some of his previous goals, like that long-desired comedy special. “I’m never going to do [a comedy special] more than 30 minutes again,” he says. “Artists shape art … but audiences also have a say. And in a world where it costs $100 to go see somebody live, when they can spend an hour at home scrolling through TikTok with their girlfriend cuddling, what do you do? I wanted so bad to have that hour on Netflix or HBO. But seeing the joy and the immediate feedback that I get when I see these crowds, and I’m making a good living, all the things I thought I wanted kind of faded away.”

A comedian’s path to the stage has always been a struggle, but we’re in a brand-new world now, one where social apps like TikTok don’t just build new comics from the ground up — they’re changing what future careers in comedy can look like. And right now, the most coveted gig in the world might just be on people’s personal screens.

“Change is hard for human beings,” Ndolo says. “YouTubers were gross until YouTubers were cool. Reality-TV stars were gross until they were cool. This is just the normal cycle of what happens. Now we’re in the age of resistance. Ten to 15 years from now, those of us who are still around won’t be experiencing this backlash. It’s about knowing your audience well and knowing that they came to you for a certain purpose. They came to laugh. I make them laugh.”