Her Rage Made Her A TikTok Star. Now, Drew Afualo Is Letting It Go

F

amed clapbacker, misogynist hunter, and professional yapper Drew Afualo is hefting two large axes above her head in a hot California strip mall.

“I need my weapon to match my energy, so maybe that’s why I feel better with these,” she says, testing the balance of the instruments. We’re only 20 minutes into our axe-throwing adventure and I’m already convinced I’m about to get shown the fuck up. In the lane next to her, her older sister, Deison, and mom, Noelle, have put down their own axes to watch. Afualo’s grip is tight. Her knee-high, black crocodile stiletto boots are sharp. Her jorts are buttoned. Her aim is true. She’s ready. “I must… become the axe,” Afualo says dramatically, before chucking both, hitting the pockmarked, wooden rings in front of us with a loud, hollow thud. “That’s light work right there,” she says, swaggering away. Horrible men should be very, very afraid.

Afualo’s no stranger to a waiting target — her first popular video was a joke about red flags in men, specifically traits that girls should run far, far away from. (If Wolf of Wall Street is his favorite movie or he wears his hat backward in the pool, do not pass go). Afaulo got why it resonated with women, but she was surprised that her “silly ass video” made so many men furious.

“It was the very first of mine that got a million views,” she says. “And I stand by it. But at the same time, I got a whole bunch of hate that I had never seen before, in any capacity. So I thought it was funny. Like ‘Oh, we’re all being silly?’ I can be silly.”

Afaulo decided to take the bullies head on — addressing every mean comment with its own video tearing her detractors to shreds. “I was just lighting [men] up left and right,” she tells me later. “It was like speed dating, just fucking them up one by one. That’s what really started getting the ball rolling.” Now, four years later, the 28-year-old is known for more than just a good retort — she’s 8 million followers deep, hosts an exclusive Spotify podcast The Comment Section, is releasing her first book, on the eve of a national 21-date tour, and has created a tight-knit community online that’s recognized that sometime empowerment means learning when to stoop to people’s level. It’s a controversial approach to content, one that only Afualo’s good-natured personality seems to temper. But as Afualo grows from a rejoinder queen to a legitimate comedic voice, the tensions that have existed her entire career have her barreling towards an inescapable crossroads. Rage made her famous. But is it something she can — or even wants to — keep up?

BEFORE SHE WAS A TIKTOK star, Afualo was the middle child of a tight-knit Samoan family — one that emphasized and celebrated female power. “I’m not new to this, I’m true to this,” she jokes, one of dozens of catchphrases and aphorisms she sprinkles in her day-to-day talk. “I’ve been this way forever. Clearly you have to love attention to some extent to do this for a living.” Growing up outside Los Angeles, Afaulo and her two siblings were raised in a traditional Samoan household, what Afualo describes as a historically matriarchal culture. Her father, Tait, who had played in the NFL, stayed home with the kids, while Noelle worked in PR. “My dad had no problem being the homemaker,” she says. “That’s just how I was raised. [He’s] always treated my mom with respect, love, and kindness. I was never worried he was gonna pull rank. They are true, equal partners in every sense of the word.” The middle child between older sister Deison and younger brother Donovan, Afualo had support and structure and love. She also had a shit-ton of anger: “It’s a running joke in my family that I was born in a bad mood.”

Once, after a boy slapped Deison’s ass at school, Afaulo jumped him in the hallway and was sent home. When her mom picked her up, Drew claims she wasn’t punished because she got into a fight — she was punished because there were so many people around to see it. “We’re very family-oriented,” she explains. “We care a lot about taking care of each other and making sure we’re all good.”

A sports fanatic, Afualo played 10 years of soccer, throwing herself — and her body — into the conviction that this was her only path to college. But a bad game during her freshman year of high school tore “everything” in her knee, leaving Afualo with an “existential crisis.” Her answer: sports journalism, with an emphasis on broadcast, which took her to the University of Hawaii. But after graduating in 2017, no jobs appeared. Instead, she had to move home and spent two years working in public relations before she got a gig in the media department of the NFL.

She thought it was her dream — all the joy of working around sports without having to risk her health to do it. But in February 2020 — three days after the Super Bowl — she was let go. Her father had been cut, too, after just two years on the Arizona Cardinals, thanks to an injury, in a way that had felt unceremonious to the family. “I think my dad felt cheated [by the NFL] in a sense. The machine chews players up and spits people out. So part of me was like ‘I’m going to do this for us. I’m gonna prove that we can be there.’ Turns out we can’t!” Afualo says, breaking into the cackling laugh that has become her signature. “My dad was the first person I talked to when I got fired, and he said ‘Congratulations!’ He was like ‘Man, they really don’t want us there.’ Girl you’re telling me. Shit. I’ll take the hint.” Afualo can talk about her path from a jobless college graduation to social media with brevity now. But at the time, living at home and convinced her dream was over, she was devastated and convinced that timing, or a lack thereof, might keep her from her dreams. Then, when Covid hit, she did the only thing she could think of: she downloaded an app.

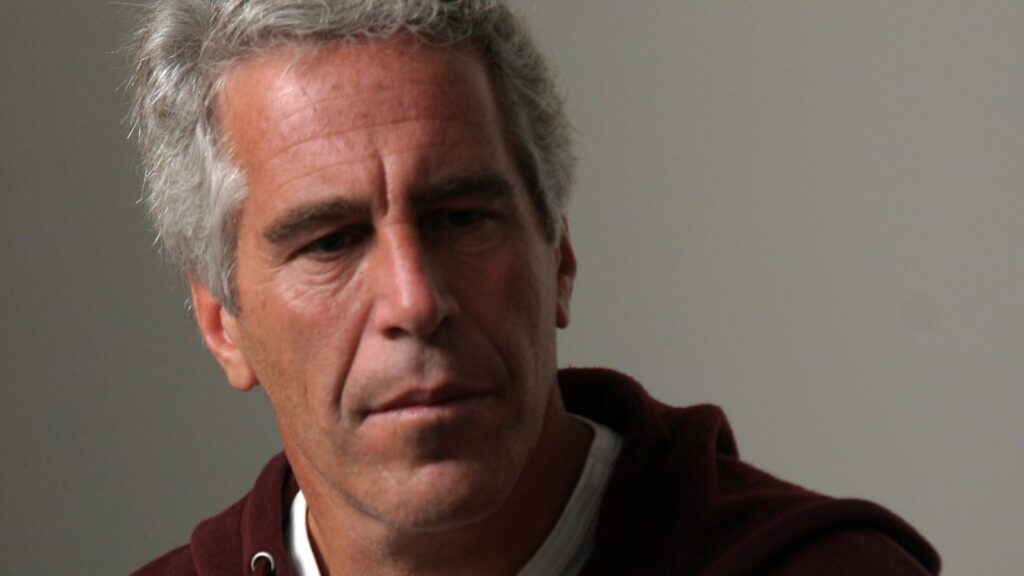

Drew Afualo in Los Angeles, June 2024

Nolwen Cifuentes for Rolling Stone

Like so many voices in the creator economy, Afualo’s time on TikTok during the pandemic radically jump-started her career. Unlike many of those other creators, she’s built hers on a burning rage. It’s a pithy approach — certainly one that TikTok’s algorithm rewards wildly. In a world surrounded by surface-level treaties to be kind or take higher roads, Afaulo gets down in the muck — firing back with clever comparisons to Muppets, Boss Baby, Beavis and Butt-Head, or plainly suggesting that men who want submissive women just buy Border Collies instead. (One personal favorite includes the quote “Your own genetics don’t listen to you, why do you think women will?”) When the insults makes men even more furious, or centers Afualo as the target of harassment, she takes on an unaffected mentality.

“If I take the power from a word, it can’t hurt me,” she says. “So you can call me the fattest, ugliest bitch alive and I’d be like ‘You’re goddamn right. Anything else?’ You go first and then I’ll talk about what you look like and then we can all have fun together. And they don’t seem to react very well to that when I’ve taken the power out of that word.”

Using this tactic, it’s taken less than four years for her to go from a recognizable poster to the leader of a loud cohort of Al Gore’s internet. But peel away Afualo’s brash persona and what you’re left with is a young woman determined to never let the people she loves feel anything less than worthy. At least, not if she can help it. The first time I met Afualo at a party and panel celebrating her inclusion on the Forbes Top Creators List, she yelled at an entire room full of influencers to “shut the fuck up” when they interrupted my friend from finishing a speech. Even just watching Afualo at the axe range with Deison and Noelle, it’s clear she’s less concerned with an interview than with making her sister smile. Every time Afualo snaps out a quick joke, her eyes dart to Deison, pushing to make any escaped smiles or giggles happen again. The air around the three is fast-paced, quick-witted, and easy. Being family-oriented isn’t an idea. It’s Afualo’s entire state of being.

It’s this vulnerability, and perhaps brand new look that might surprise die-hard fans about Afualo’s debut book, Loud: Accept Nothing Less Than the Life You Deserve. Releasing July 30 on Questlove’s imprint, AUWA Books, the book has been billed as a “part manual, part manifesto, and part memoir,” meant to capture Afualo’s fleet of hardcore followers. What it actually feels like is a confession. In Loud, the Afualo of TikTok fame is slowly peeled away, examining how the rage that got Afualo her career has made other elements of her life worse. She isn’t just TikTok’s anti-misogyny caped crusader. She’s the sister who regrets being upset when Deison came out to her. The daughter who is conscious of how her fury made childhood difficult. And she’s a creator who built her platform — and life — around fury, learning how to let that heat go and encouraging others to do the same.

“My [relationship to anger] has changed drastically,” she says. “And I’m grateful for it. Having no fear is not a good thing. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve realized that not everything is worth that type of rage. It doesn’t serve me. Does that mean I won’t fight? No. If I have to turn into the Incredible Hulk then I will. But I get to decide.”

IN PUBLIC, AFUALO TREATS insults like physical powerups, cackling in person and online about harsh words, descriptions, and sometimes vile threats made in response to her posts. But when she talks about threats to her family, the image, and her feelings crack. After her first major influx of followers in mid 2021, Afualo got targeted rape and death threats focused on the support system around her. And that made her nervous. “It starts to cross boundaries when it’s death threats,” she says. “At the time, my brother was in public school, where my boyfriend was working. I don’t know who the fuck is gonna show up there. Threatening my life is one thing, but threatening the lives of people I love was really the only thing that made me feel like, ‘I don’t know if I can do this.’

Drew Afualo in Los Angeles, June 2024

Nolwen Cifuentes for Rolling Stone

It took having her family lock down their socials, a pep-talk from her mom, and strict security advice from some (unnamed) creators for Afualo to stop thinking about quitting. But even now, there’s a clear sense of frustration that her dream career has come with so many personal concessions, like not being able to attend events like birthdays, baby showers, or weddings.

“It’s changed a lot about the way I see myself and how I choose to operate in dynamics with people who don’t do this for a living and have no desire to,” she says. “And my friends don’t care, but I do. Even my sister’s first Pride Parade, that was really exciting for us and I wore a wig. It was so much fun but I got mobbed at one point and we had to leave. I felt like I was taking away attention. And she didn’t see it that way, but it just makes me feel awful. So I just remove myself entirely. It makes me feel like I’m missing out on milestones for people’s lives.”

This vulnerability isn’t just hidden away in Afualo’s head or therapy sessions anymore. In the past few months, ahead of the release of Loud, she interviewed rising pop sensation Chappel Roan for The Comment Section, where the two commiserated about how their fame drastically changed their lives. Roan surmised it best: “I miss being a freak at the bar.” Afualo has grown from the college grad laughing at bald men while living in her parent’s house to a woman who’s learned that anger isn’t always the solution. So it’s not shocking that Afualo doesn’t think she’ll be able to keep up this energy, or this job, forever.

“Times are rough if I’m still doing this when I’m 45,” she jokes. “I can’t do this forever, for many reasons. But one of them being [trolls] never get any more creative. They never get smarter, they don’t get funnier, they just say the same shit 1,000 ways. I can only make fun of a hairline in so many ways before it gets redundant.”

Afualo says her book and her next steps, whether it be a tour, a podcast, or taking a few minutes out of her day to cut a rude dude down to size, is in the hopes that women realize they can do it too.

“I don’t have anything special, no superpower to not get hurt when men call me fat or ugly, or all this other bullshit that they say,” she says. “I don’t have some sort of super forcefield around me that blocks things. I’ve just done the work to base my validation in something that is not centered around my looks. And that’s only happened because I’ve torn everything I know about myself down to my eyes, and my brain and my goals and my dreams. The only person who gets to decide what does and doesn’t hurt is me.”