‘Halo 2’ Is a Classic, But Its Development Was a Mess

It’s hard to believe that it’s already been 20 years since the release of Halo 2. Launched for the original Xbox on Nov. 9, 2004, and following the very high bar set by 2001’s Halo: Combat Evolved, the game could’ve easily been a disaster (a fate saved instead for later sequels). Instead, Halo 2 proved to be not just a perfect follow up to Xbox’s flagship title, but one of the best games ever made.

The extent of Halo 2’s massive success has been well-documented over the last two decades, as has the famously difficult development of the game. Though beloved first person shooter shattered sales records and eventually became the best-selling game on Xbox, Halo 2 nearly broke the team working on it, including Robert and Lorraine McLees, the couple responsible not only for some of Halo’s most iconic visuals, but for much of the lore that drove the sci-fi juggernaut franchise and the extended media that spun out of the games.

Ahead of the game’s 20th anniversary, Rolling Stone spoke with the duo about their work on what many die hard fans still believe is the best Halo game of the series, to learn more about the struggles, sacrifices, and shifting responsibilities that went into making Halo 2. Their story is a stark reminder of the perils of crunch and the unsustainability of early aughts game-making — though Halo 2 is beloved by most, its developers suffered through a painful production process that resulted in stress, sabbaticals, and even some leaving the industry for good.

A different era for game design

Looking back, there were highs and lows, but both Robert and Lorraine speak fondly of their time working on Halo 2. Robert was Bungie’s fifth ever employee, and started at the company as an artist on 1995’s Marathon 2, while Lorraine was brought on to finalize the original Halo game’s logo. The game and its galaxy-spanning universe, led by a monosyllabic super soldier in an indestructible suit of armor named Master Chief, clearly seeped into every corner of their lives — Robert and Lorraine didn’t just design assets, but worked on Halo graphic novels, wrote in-game lore, designed UI, and much, much more.

Thanks to the current standards of larger developer studios and more clearly defined roles among teams, you’d be hard-pressed to find a modern AAA game that has lore written by one of its weapon artists, or its most iconic character (in this case, Master Chief) partially defined by the work of the person designing the box art logo. As games have gotten bigger and more costly to produce, developer teams have ballooned in size, and the major decisions are now almost solely reserved for game leads or studio heads.

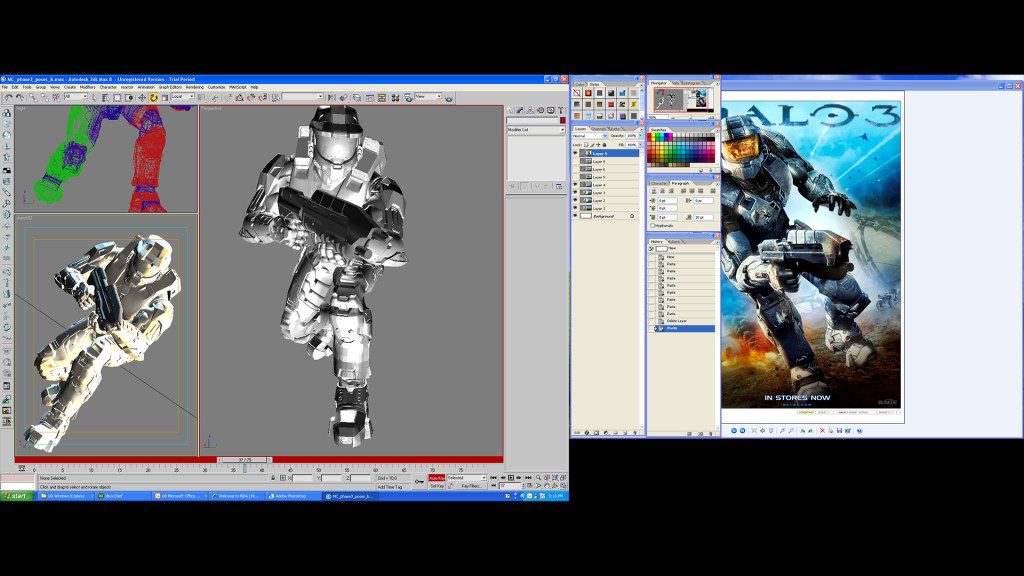

Master Chief is the face of Halo, but was almost left out of the sequel’s marketing.

Microsoft Game Studios

Halo 2 was made, in every sense of the phrase, during a vastly different time in video game history, one that will never be replicated (for better and for worse). That it became the best-selling game on the original Xbox and is still widely considered the greatest title in the franchise isn’t a fluke, but speaks volumes to the immense work put in by everyone involved, even at their own personal toll.

Halo 2’s power couple

If you take a second to reminisce about Halo 2, chances are you’ll conjure up the imagery of something either Lorraine or Robert worked on. By the time Bungie was working on the game, Lorraine, who came on as the art director of marketing at Bungie in April 1999, and finalized the Halo logo just ahead of its grand reveal at MacWorld that year, was hard at work redesigning key art and outlining the shape of the “2” for the sequel’s logo.

That logo, she says, was inspired by environment artist Paul Russell’s Forerunner architecture designs. But Lorraine and others weren’t too fond of the Microsoft marketing team’s original pitch for how they planned on selling the sequel to audiences, which she describes as, “the extinction of mankind [being] the primary focus, not once showing the player character [Master Chief].”

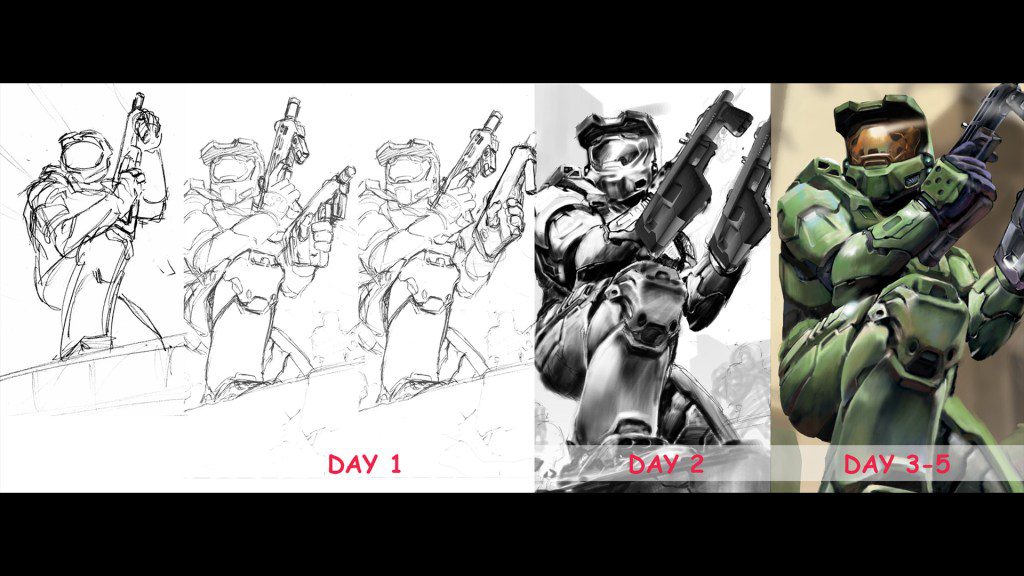

Lorraine’s cover art for Official Xbox Magazine’s E3 edition, 2003.

Art by Lorraine McLees; Xbox Game Studios; Official Xbox Magazine

According to Lorraine, it didn’t sit well with the team that the primary hero wouldn’t be the center of the sequel’s marketing push, so she began steering them towards a more Chief-centric strategy. “It started with my illustration of the dual-wielding Chief on the cover of the Official Xbox Magazine,” she says. “I then created the source art the marketing team at Microsoft built the campaign around — including additional magazine covers. In all of that we wanted to make sure the audience got to see our primary hero at the center of the action.”

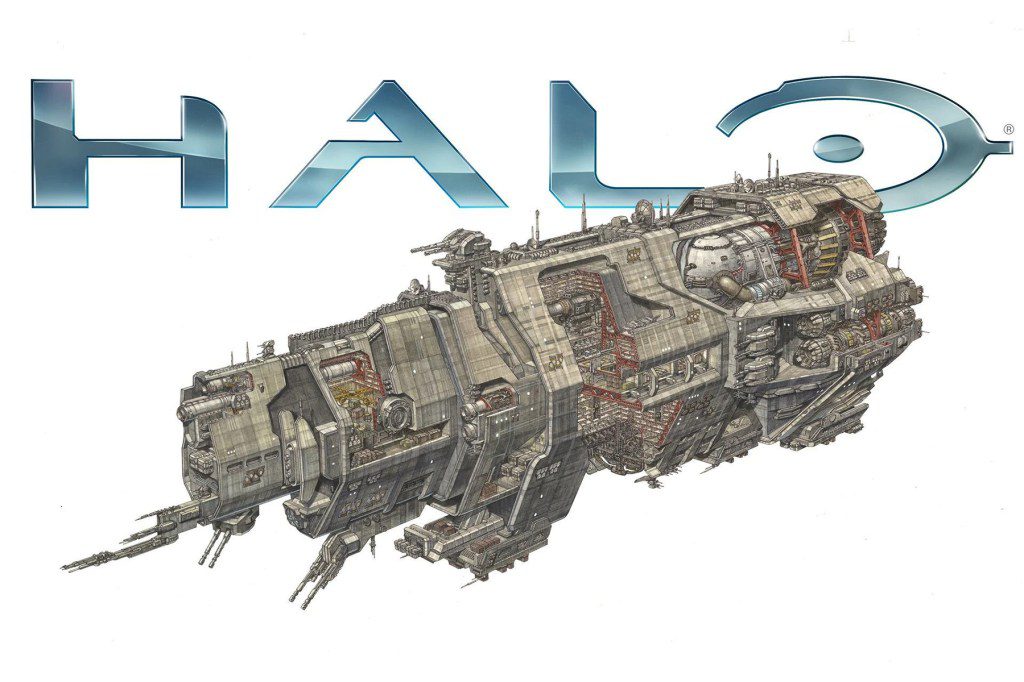

Lorraine also designed the famous Pillar of Autumn, one of humanity’s spaceships used in the fight against the alien military alliance known as the Covenant. Funnily enough, she based her design of the ship on the MA5B, the Halo: Combat Evolved assault rifle that was designed by, you guessed it, her husband, Robert McLees.

“I was kind of the weapons guy at Bungie,” Robert explains. “I was also the most senior artist by a couple of months, at least. So, I did first pass on all the weapons and vehicles, except the Warthog, which was Marcus Lehto’s baby. I did a very early pass on the main alien enemy [Elites] — they used to have a more snake-like head and conventional jaw — and I even made a prototype map back when Halo was going to be an open-world action game.”

The Pillar of Autumn, designed by Lorraine based off a weapon created by her husband.

Concept art by Lorraine McLees; Xbox Game Studios

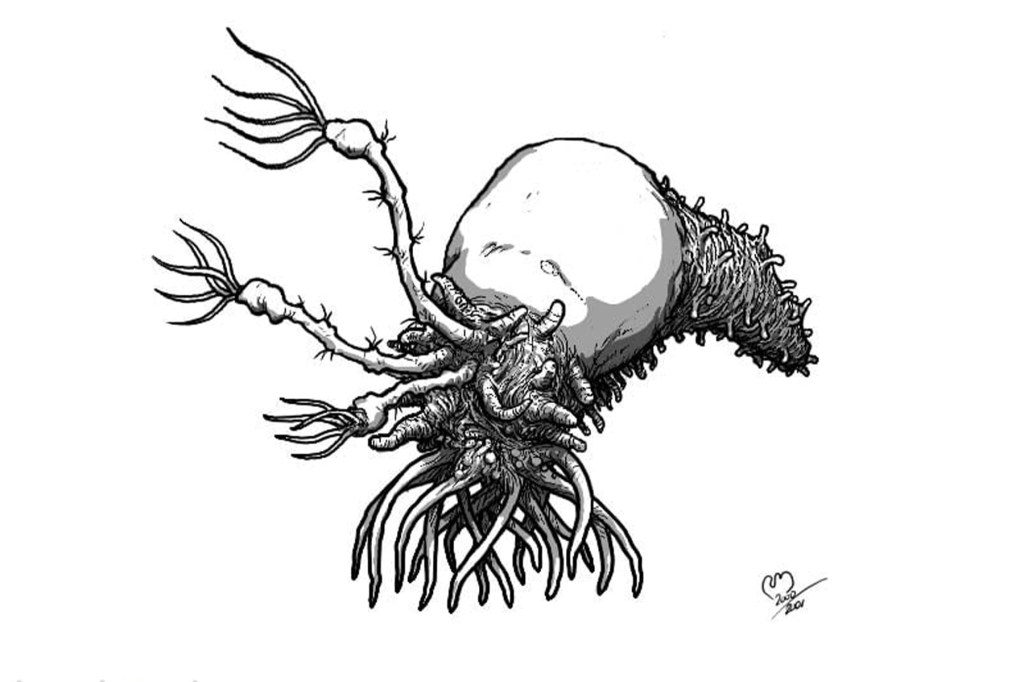

For Halo, Robert pulled inspiration from, “kind of everything,” including “low budget sci-fi movies from the Fifties and Sixties, World of Tomorrow type film reels, prototype cars and guns and tools that failed, hotrod culture, underground comics.” But for the Flood, the zombie-like enemies that appear in Halo 1 in one of the scariest moments of fans’ collective gaming memories, Robert drew inspiration from a very unlikely place. “Some of it acted on me unconsciously,” he says.

Robert initially pitched the enemies as the result of humanity’s first encounter with an alien life form and their incompatible biologies, a cordyceps-like infection. “When the Flood became something other than an infection, it looked like a cross between a house centipede and a blood sausage,” he says. “That was disgusting, but didn’t look very mobile. So, there’s this shape that had been skittering around in the shadowy parts of my brain that became the classic infection form.”

That shape wasn’t slithering around in a horror movie, or conjured from the depths of a haunted house, but a children’s book, of all places. “When my daughter was born, I gathered up all those Golden Key books I remembered from my own childhood so I could read to her before she went to sleep at night. And there it was, in The Saggy Baggy Elephant, a palm tree launched into the air by dancing elephants — the weird shape that had been haunting my subconscious mind for thirty-odd years. That was the basis for the Flood Infection Form.”

The Flood came to Robert subconsciously from a children’s book.

Concept art by Robert McLees; Xbox Game Studios

And this is why Robert McLees is known amongst the Halo community as “The Father of the Flood.”

Both Robert and Lorraine’s iconic contributions to the Halo universe didn’t come without a cost. “Halo 2 really took a toll on me,” Robert says. And he wasn’t alone in that sentiment.

A hellish development

“Halo 2 was really hard on the team,” Lorraine explains. “The whole studio was burning the candle at both ends.” Other devs have spoken extensively about the inhumane amounts of crunch that went into Halo 2’s production, which was hampered, in part, by the infamous E3 presentation (an 8-minute “demo” of a level that never made it into the final game), but also by what Robert says was a serious leadership issue at the studio.

“Bungie, up to then, never had good managers,” he says. “They had creatives that were forced into managerial roles while still remaining in their creative roles — basically working two jobs. This kinda worked when there were 12 of us. It worked less well when there were 30 of us. It collapsed when there were 60 of us.”

That collapse led to tons of unnecessary extra work, especially since, to Robert, “it felt like every discipline lead thought that they were running the show.” This meant that there was little communication between departments, “just a bunch of different voices saying, ‘this is what we’re doing’ and a lot of people scratching their heads wondering ‘when was this decided?’”

Assets were being requested under crunch, yet left on the cutting room floor.

Xbox Game Studios

This was especially frustrating for Robert, who was working to create tons of assets for Halo 2, including all of the minutiae and set-dressing necessary to hammer home humanity’s role in this sci-fi war. He designed ammo pickups and crates, health items (Meal, Ready-To-Eat!), and just about everything needed to flesh out the look and feel of the environments. But, at the same time, he was also writing combat dialogue, foundational fiction that added necessary depth to this expansive lore, and named “every single one of the alien races,” because he was, in his words, “obstinately old-school” and couldn’t help adding his own flavor to every Halo 2 dish.

The consistent lack of communication between departments meant he was often doing even more work than was required of him. He recalls a time when he was asked to design an entirely new weapon just two weeks before Bungie entered the polish phase of development. “[The weapon] hadn’t been placed in any levels, hadn’t been tested in multiplayer or campaign, and it had to look good being held as a low support for the Chief, a high support for the Grunt, and a rifle for the Elites,” Robert says.

He delivered the multifaceted design for it under the crunch, only for the weapon in question to ultimately end up cut from the final game. “How the fuck does that request make it all the way to me?,” he wonders. “There were at least three stages where it should’ve been killed before it got to art.”

Lorraine worked tirelessly for the game, but is proud of its legacy.

Art by Lorraine McLees; Xbox Game Studios

Robert wasn’t the only one pulling double duty. Lorraine would put their baby to sleep on her desk after daycare (“since we had crazy hours”), so she could do a ton of “thankless” but “fun” work on the sequel. “My title never matched my actual responsibilities,” she admits. “We were too busy. At some point, I stopped caring as long as I got to do the work.”

“At the time, we really didn’t know what was going to happen — if we were going to make it or not,” Lorraine says. “It was the make it or break it period for the young Bungie crew. So much burn-out.”

A complex legacy

Despite all that, when Lorraine looks back on the legacy of Halo and her role in shaping it two decades later, she does so with a fondness. “Even the electrician who came in this week saw our trophies in full display in the dining room and living room, and they were giddy with nostalgia — the good times they had in college playing Halo games on LAN and later over Xbox Live.”

It’s a memory that many elder millennial gamers share, one that makes those first few Halo games so special, and what hammers home the importance of the work Robert, Lorraine, and the rest of the developers did under grueling conditions.

“These stories of people staying in touch with friends, though life took them to different parts of the country or the world, meeting up in the lobby, then doing a few rounds in Halo 2 — to me this is what the takeaway is,” Lorraine says. “We helped bring people together. Experience some joy. Have fun. Make memories. That’s the power of these games.”

Master Chief remains an iconic figure in pop culture.

Xbox Game Studios

It’s easy to forget the actual human beings that are behind genre-defining, record-breaking games like Halo 2, and it’s even easier to overlook just how much they gave in order to ship the game. To some degree, much of the industry has shifted away from such grueling workloads and intensive crunch that exemplified the development process back in the early aughts. But it hasn’t gone away entirely, and remains an ongoing issue for studios to reckon with.

More of an issue is the ever-inflating size of development studios for short-term sprints of design. While major companies like Sony and Microsoft chart long running road maps for years-long development — often amounting to nothing — the industry has also lost its sense of scrappiness. There no longer exists a kind of game development where a lowly weapons artist has a say in the lore, or a logo designer can fight the good fight to ensure a character like Master Chief gets his due. It’s all more corporate than that.

Yet for all the crossed wires, babies sleeping on desks, and months of extracurricular work, Lorraine wouldn’t change a thing about her time working on Halo 2: “I am forever grateful for being part of it.”