Floods and Storms Are Ravaging the Jersey Shore. Why Do We Keep Building It Back?

W

hen Hurricane Sandy rammed the Jersey Shore on the night of Oct. 29, 2012, saltwater fisherman Nick Honachefsky was living in Camp Osborn, a community of tiny bungalows a mile south of Mantoloking on Barnegat Bay Island. Earlier that day, Honachefsky had taken a bottle of Captain Morgan rum with him on a walk down the beach, figuring the arrival of a hurricane meant it was time to start drinking and take a few pictures. The news that cops were banging on doors, telling people who were insisting on riding out the storm that they should write their Social Security numbers on their wrists so their bodies could be identified later — plus a phone call from his worried mom — made Honachefsky decide to spend the night at an ex-girlfriend’s house on the mainland.

A few hours later, the storm’s surge roared on top of a high tide across the skinny barrier island, opening broad new inlets as the Atlantic poured up Barnegat Bay. Most of the bungalows that made up Camp Osborn, including Honachefsky’s 750-square-foot house, were washed away. A friend of Honachefsky filmed the storm’s arrival. “He’s like, ‘I think I did see your house. It was the blue one, right? Yeah, it’s floating down Route 35. It’s on fire,’” Honachefksy remembers. When he was finally able to return to the site of Camp Osborn 10 days later, Honachefsky saw 30-foot flames of gas still shooting out of the ground. “It looked like the oil fields in Kuwait,” he says. An exploding transformer had kicked off a fire that continued to burn; there was no gas shutoff valve for the island.

Today, when you stand where Honachefsky’s small blue house used to be, here is what you see: identical mammoth white duplexes built tall above ground-floor parking areas, with construction stickers still on their windows. At one end of the passageway between the new buildings is a giant sand dune, planted with seagrass, over which a webbed fabric walkway stretches to the wide beach and rolling Atlantic beyond. If you stand a few hundred feet to the west, on the bay side of Barnegat Bay Island, you can see the Mantoloking Bridge connecting the narrow spit of sand where Honachefsky used to live to the marshy fringes of the mainland. During Hurricane Sandy, the storm’s surge washed houses and sections of roadway onto the bridge’s approaches. After the storm, the dunes were rebuilt. Some old residents returned — and new, much wealthier residents flocked to fill the gaps.

“This particular part of the barrier island is a special place for me,” says Honachefsky. On a hot July day, he’s standing on top of the newly rebuilt dune, looking out at the ocean. “From my dad taking me fishing here when we were kids, and my cousins living here, and friends in high school with their families having houses . . . This little spot here, this is the beach. I know these sands.” This is the first time since the storm Honachefsky has made his way to the dunes through the large, elevated duplexes that have replaced the bungalows of Camp Osborn. The roads and buildings he knew have vanished. “It feels foreign, alien,” he says. But he wants to buy back in as soon as he can figure out a way to afford it. “There’s only one place for me to live,” he says. “My soul is here.” So far, it’s been far too expensive a proposition.

Nick Honachefsky standing in the wreckage of Camp Osborn post-Hurricane Sandy

Courtesy of Nick Honachevsky

THE SERIES OF BARRIER ISLANDS and inlets that make up the Jersey Shore stretches 30 miles north of Honachefsky’s former home, up to the narrow spit of Sea Bright and Sandy Hook, and roughly 100 miles south to the tip of Cape May. In summertime, the treeless main thoroughfares of the mid-Shore stretch for miles under the glaring sun, festooned with electrical lines. Glinting lines of cars inch up and down, heading for infrequent bridges coming from the mainland or away from it. At some points the sandy spit is narrow enough that it feels like a strong arm could throw a baseball from the Atlantic Ocean to the bay. On the side streets, a few small houses — living room and damp kitchen below, tiny bedrooms above — are overwhelmed by newly-built, multimillion-dollar creations bristling with decks and pools, set in gravel yards. Restaurants, bars, miniature golf courses, and ice cream shops are tucked into the sandy low landscape, along with water towers marking town names and occasional pleasure piers and Ferris wheels.

But the whole shore, every square foot of which has fulfilled someone’s American dream of living right on the beach, is sailing toward disaster. Seas are rising more than twice as quickly off the Jersey Shore than the global average. Already, ordinary high tides coming up from the bays between the rest of New Jersey and the barrier islands routinely overwhelm drainage systems, flooding streets and threatening houses. As the air and oceans continue to warm, high-tide flooding events, which happen a few days a year right now, will occur 120 days per year on average by the middle of the century, according to Robert Kopp, co-director of the Rutgers Office of Climate Action. By 2100, Kopp says, such floods “will basically be the new normal” along this coast, and sea levels will be several feet higher. Storms are growing in intensity, too: Over the last 50 years, storms resulting in extreme rain increased by 71 percent in New Jersey, faster than anywhere else in the U.S. In August, Hurricane Erin hammered the length of the Shore, causing major beach erosion and coastal flooding; an October Nor’easter brought more damage to the beaches.

Complicating matters, all of the Jersey Shore’s precious real estate is built on shifting sand. A cluster of barrier islands that emerged after glacial retreat 10,000 years ago, then melted and reformed over the years, today’s Shore is effectively a series of sandbars. Left to their own devices, they would continue to roll and change, and much of the area would be swamped by chronic flooding as the oceans rise in the decades ahead. So far, the preferred solution to this unfortunate reality has been to try to keep things as they are using artificial means.

Many sections of today’s concrete-covered Jersey Shore are as natural as parking lots, kept in place by bulkheads, seawalls, and billions of dollars in sand dredged from the ocean. For the past 35 years, mountains of sand — enough to fill the typical NFL stadium at least 40 to 50 times — have been pumped onto the Jersey Shore at a cost of more than $3 billion, the bulk of the spending coming from the federal government. That’s more beach nourishment money per length of shoreline than any other place in the United States, according to Rob Young, director of the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Western Carolina University.

But seawalls that we imagine are mitigating erosion can actually accelerate it, as waves scour away sand directly in front of them; at the same time, they reflect destructive wave energy back onto beaches nearby. By trapping sand on one side and keeping it from drifting with the tides, jetties and groins (manmade barriers built straight out into the water) create costly cycles of artificial sand nourishment aimed fruitlessly at keeping beaches intact. Any child building a sandcastle soon learns that it is no match for the sea.

Jetties like this one constructed to protect mansions in Deal, New Jersey, can actually worsen coastal erosion by preventing the natural movement of sand.

John Moore/Getty Images

Sandy should have been a wakeup call that spurred a collective rethinking of what the Jersey Shore looks like in the future. Instead, nostalgia, developer influence, entrenched municipal autonomy, and a powerful real estate market have fueled explosive development. And now, as rising sea levels and worsening storms loom, the federal funds that have covered past adaptation efforts in New Jersey are disappearing. Many of the Army Corps of Engineers programs that subsidized beach-building in New Jersey were 50-year agreements that are set to end around 2040. No new beach replenishment programs are being authorized nationwide, and President Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill contained no money for sand. Much of this is simple cost-cutting; the Trump administration has said that local or state governments — not federal taxpayers — should bear responsibility for these projects and for disaster recovery.

New Jersey is not alone: States from Florida to Maine are grappling with this problem, as houses fall into the sea in North Carolina and beaches vanish in Maryland and Virginia. Actions aimed at lowering the physical risks of living in increasingly wet places have been mostly reactive, small-scale, ad hoc, and reliant on federal aid. Local governments, dependent on property taxes to run their emergency services and schools, are understandably wary of taking the transformative steps needed to keep people safe in the long term.

If money were no barrier and political crosswinds didn’t exist, wise public policy steps would include stopping development in risky places, helping people gradually move out of harm’s way (a strategy sometimes referred to as “managed retreat”), and steadily reducing support for publicly-funded infrastructure in places that are becoming less livable. States would prioritize their investments, and cities would find ways to work together. As things stand now, though, dramatic action is not on the table.

The Jersey Shore encapsulates this larger story. What’s likely to happen there by the turn of the century? “We’re going to have places where only wealthy people can live,” says Peter Kasabach, executive director of the research and policy nonprofit New Jersey Future, which promotes fair and resilient growth. Richer residents will work around the inconvenience of coastal flooding, he says, and walk away from their houses when they feel like it — if they haven’t been able to sell. “Only certain people are even going to be able to access the Shore,” he predicts. So far, Kasabach’s vision is coming true. He’s not happy about this, adding: “I’d like to be wrong.”

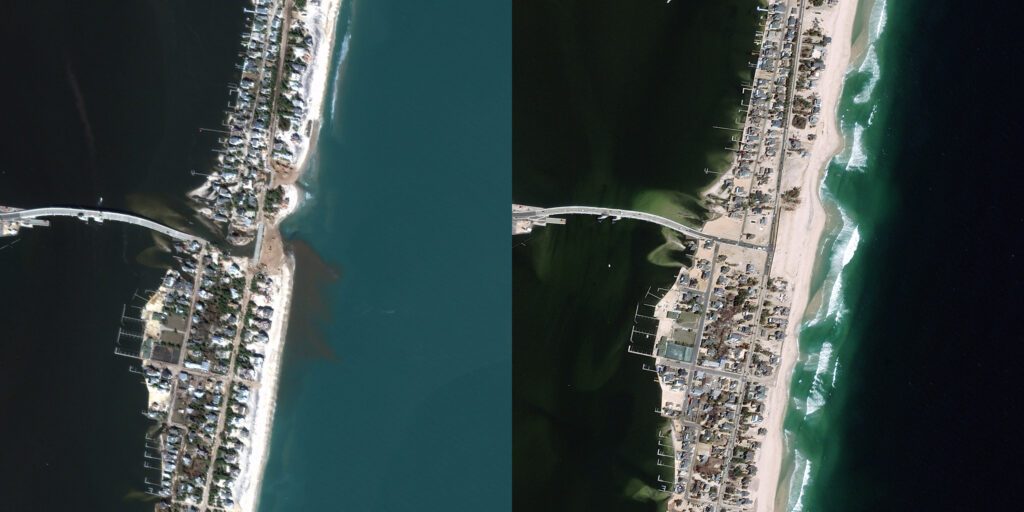

Satellite images of Mantoloking on Nov. 4, 2012 (left), and April 6, 2013 (right), after the beach was rebuilt

DigitalGlobe/Getty Images

THE MODERN JERSEY SHORE began decades before twentysomething Nick Honachefsky spent evenings drinking at the Crab Claw and catching a ride back to Camp Osborn from a cop. What transformed a mostly dune- and marsh-filled series of islands into a mainstream tourism destination was the opening of the Garden State Parkway in the region in 1954.

Summer visitors flooded in from Newark and Philadelphia, buying small lots on the barrier islands near bridges fed by exits off the Parkway. No one was checking the developers’ homework very carefully. Kevin Wark, a master fisherman who was born in the town of Ship Bottom on Long Beach Island, remembers his dad talking about “guys that dug lagoons without permits.” Wark still lives near the northern end of Long Beach Island, south of Mantoloking. “All that bay road back there, that was all marsh meadows when my dad grew up,” he says. The developers built tiny lots overnight of dredged sand. “You know how these small-town politicians are,” Wark says. “They’re pretty shameless, most of ’em.”

In the Seventies, when Wark was a teenager on Long Beach Island, his buddies were all surfers. “You had a surfboard and a metal clam basket so you could go make money,” he says. “That was our stuff.” Wark remembers that “you could lay in the road at Barnegat Light and not get hit by a car. I can remember plenty of guys passing out after fishing trips and sleeping in the weeds over there. Nobody would find them.” Wark’s great aunt Virginia Thompson called Long Beach Island “that horrible desert with those big sand dunes.”

Tiny houses were often filled to the brim with family members. Tim Dillingham, former executive director of the American Littoral Society, a nonprofit focused on coastal conservation, remembers life in his wife’s family Shore house in Belmar, north of Mantoloking. They were second-generation Italian immigrants who lived in Newark and built a kit cabin from Sears, Roebuck on their lot, part of the first generation of strivers bent on securing their piece of the Shore. The original floor plan was one room with a little kitchen and a little bathroom. “They would hang bedsheets to divide it up into rooms,” Dillingham says. “And then as they got a little more money, they put rooms in and added on.” The entire family came down for the whole summer, celebrating every birthday in their tiny backyard.

A rising drumbeat of storms arrived and wreaked havoc. People still know them by their dates: 1962, 1971, 1985, 1991, 1992, 1999, 2005, 2011. Then Superstorm Sandy changed the story of the Jersey Shore forever.

“My friend was like, ‘Your house was the blue one, right? Yeah, it’s floating down Route 35. It’s on fire.’”

Nick Hornachefsky

Sea Bright resident Dina Long was in the first year of her first term as mayor when the storm made landfall in 2012. Thinking they were about to go through another Irene, the hurricane from the previous year, with a few inches of water making its way into their house, she and her husband put their couch on their dining room table the night before and left town.

At 5 a.m., the town’s emergency manager called her, saying, “Prepare yourself. Sea Bright is gone.” He was right. “Everything was wrecked,” she says. Five feet of water had rushed across the small town, making it temporarily part of both the Atlantic Ocean and the Shrewsbury River to the west. Sea Bright’s main street was covered in six to eight feet of sand. All of the town’s municipal buildings were gone. All the businesses, the surf shops and little cafes, were devastated.

Following Sandy, there was an enormous sense of urgency from then-Governor Chris Christie’s office to get people back into their places on the Jersey Shore in time for the next vacation season. Christie made a TV ad with a catchy jingle — “We’re stronger than the storm!” — and prioritized quick financial rebuilding assistance to individual homeowners and businesses rather than requiring any statewide or community-wide planning process for an increasingly risky future. His administration focused on enhancing existing dunes and building new ones but avoided more complicated questions about needed changes — including recognizing past mistakes.

Thanks in large part to Christie’s initiative, Sea Bright, like the rest of the Jersey Shore, has gone the opposite way from what land use experts urged, experiencing tremendous growth and development since Sandy. “We did our [rebuilding] job too well,” Long says, wryly. Since 2016, she says, half of the properties in her town have been bought by new owners. Home prices along the shore have doubled — or more — since 2012, rising to an average of about $550,000, and many of these new homes are not lived in year-round. “Hurricane Sandy wiped the slate clean and then let fundamentally unfettered development come in,” says Dillingham. The rationale for all the reconstruction and the public support and the relaxation of zoning rules was that “they needed it done in the name of the public to restore the Shore.”

Even though — or perhaps because — tens of billions of dollars in property values are now heaped up along the Shore, there is no appetite for transformative planning for the physical effects of climate change that are ahead. People are “hesitant to even talk about what does the island look like in 2100, let alone try and have a serious conversation about what they want to do about it,” says Nick Angarone, the state’s chief resilience officer, a position created under Governor Phil Murphy. “We’ve made some improvements, but we’re not that much safer from a Sandy-type event.”

Things are reaching a critical point, because it is suddenly unclear where money to continue shoring up the Shore will come from. “We’re entering a newer dangerous phase for the Jersey Shore,” says Rob Freudenberg, vice president of the Regional Plans Association. Even if beach sand is ineffective in protecting residents who live behind the first row of beachfront houses, it is helpful for tourism — an industry that brings tens of billions of dollars into New Jersey annually.

A man jogs past a beach replenishment project in Belmar, New Jersey, in April 2014.

Wayne Parry/AP

“We haven’t lived with the lack of federal dollars that went into holding this system in place for decades and decades,” says Freudenberg. Since Sandy, more than 90 percent of New Jersey’s $7 billion in spending on climate adaptation projects has come from the federal government, most of it post-Sandy money; Atlantic City, surrounded by water and eroding around its edges, alone received over $100 million in federal and state investment for bulkheads, pumps, and stormwater improvements. Today, almost all of the Sandy money has been spent or fully allocated. FEMA announced earlier this year that no new adaptation funding would be forthcoming. The state’s budget is extremely tight. “New Jersey does not have a stable source of funding for resilience activities,” says Angarone. He adds: “Whether there’s going to be some type of investment at the state level is, I think, very much in question at this point.”

The federal drawback worries Edward Mahaney, the former mayor of Cape May, at the shore’s southern tip. He has been involved in Jersey Shore local government for more than 30 years, but has never seen a crisis like this. “You have to keep playing chess with Mother Nature and staying one move ahead,” he told me when we met in his office, pointing at a large aerial photograph of his town. He showed me where jetties built to shield an inlet had blocked sand from drifting down the shore, causing Cape May’s beaches to vanish by the late 1980s. “In a high tide we all had to sit on top of the rock piles,” he says.

“Once you put a soil retaining structure, like a bulkhead or a rock [pile] to make sure the shoreline stays where it is, all the supply of sand that used to be released through erosion during storms is no longer available,” explains Tom Herrington, acting director of the Urban Coast Institute at Monmouth University. “By closing these sediments off,” up and down the Jersey Shore, “they pretty much took the beach out of the coast until we came back and rebuilt them,” he says.

The southernmost section of Long Beach Island is a nature preserve that does not get federal sand; rolling in the wind and waves, this part of the island has shifted more than 100 feet closer to the mainland over the last 25 years, showing what happens when water and sand are left to their own devices.

“People are not interested in imagining the future. It’s hard to imagine [the Shore is] not always going to be there.”

Nick Angarone

“We’re standing on a sand bar the Army Corps of Engineers has invested billions of dollars in to keep in place,” Shawn LaTourette, commissioner of the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, told me when we met near the preserve. “It’s washing away. And we’re spending hundreds of millions of dollars every year to fetch it and put it back.” Newly-named Horseshoe Island, massive and sandy, recently appeared south of Long Beach Island, likely fed by sand from the beach replenishment activities north of it.

Cape May was the first Jersey Shore town with a 50-year federally-backed beach replenishment project. Today, its beaches are 10 to 20 feet higher and hundreds of feet longer than they were 40 years ago. But Jersey’s beaches need maintenance every two years or so as the sand washes away. “If this beach replenishment program isn’t continued,” Mahaney says, “that’s a big problem.”

Drinking water, sewage removal, stormwater management, leaky pipes, road maintenance and elevation, pumping sand, building seawalls and bulkheads — it’s all wildly expensive to keep up with as seas rise and flooding increases, and there is no obvious funding for this work along the Jersey Shore. Today, Cape May relies for most of its drinking water on the roughly two million gallons a day produced by a desalination plant the town built 30 years ago after its wells turned salty — and it’s not nearly enough. “That plant needs to be expanded,” says Mahaney, but there’s no money to do it. He’s also worried about flood protection walls and rock piles that haven’t been funded, and what it will cost to replace and expand stormwater pipes exposed to ocean waters.

THAT HASN’T STOPPED the building. In Holgate, 30 miles south of Mantoloking, Angela Andersen, a longtime Jersey Shore resident, took me to see huge new houses with rooftop decks and pools standing on fill next to a marshy area that the township has protected as open, conserved land. The houses have their own private bulkheads, walls erected to keep the marsh at a distance. “We want it,” Andersen says of the houses’ proximity to the beach. “We can’t help ourselves. It’s the human condition… We’re loving this place to death.”

We passed two white panel trucks displaying the words MANCINI CUSTOM HOMES in bold blue lettering. BUILDING LBI SINCE 1954. Joseph Mancini, president of Mancini Realty Co. and Mancini Custom Homes, has been mayor of Long Beach Township since 2008.

“Everybody’s going up,” building enormous elevated houses on existing 50-by-100-foot lots where small seasonal bungalows once stood, Andersen tells me. “Now you’ve got 10 times the amount of people living on the same lot, and a lot of times renting and rotating.” Wark, the master fisherman, says of Long Beach Island, “They’re putting [the houses] up like three feet and putting retaining walls around ’em. But the roads are still going to be low. And I see all these weird Band-Aids and a lot of denial and a lot of money, money, money.”

A house being rebuilt on Ortley Beach two years post-Sandy. “Everybody’s going up,” says one longtime local resident of the proliferation of elevated homes.

Kena Betancur/Getty Images

Peter Kasabach of New Jersey Future points out that neither private market forces nor public entities are adequately accounting for physical risks along the shore. “After Sandy, we thought for sure that values were going to start going down at the beach,” he says. But exactly the opposite happened. And neither the federal nor state government has helped embed risk into the marketplace: The combined safety net of FEMA, the state, and insurance proceeds has made residents believe they will always be bailed out. “We should want to protect people who are taking rational risks, not people who are taking advantage of this imbalance between risk and reward,” Kasabach says.

New Jersey’s outgoing governor, Phil Murphy, a Democrat, issued an executive order in 2019 that created the role of chief resilience officer and an interagency council to confront New Jersey’s climate change challenges using “the best available science,” and called for statewide planning efforts to incorporate climate change considerations — which could, theoretically, include long-term planning to stop and shift development in risky areas. And yet very little has happened, substantively. Money and the power of developers have been barriers to any change: “We are an extremely balkanized state in that we have 564 municipalities, each with its own government, each with its own property taxes largely funding that government,” Angarone points out. “The money associated with the Jersey Shore, with our coastal area, has made action there much more complicated.”

For the last five years, Shawn LaTourette’s agency has been working on a draft rule — the Resilient Environments and Landscapes, or REAL rule — that incorporates updated climate science in building requirements and elevation rules for new construction in coastal zones. The REAL rule would have gone into effect in August, but, Dillingham says, the Murphy administration “succumbed to a misinformation campaign and political pressure from the developers as well as the [Shore] mayors,” who forced revisions to the rule that reduced its footprint and delayed its effects. Dillingham doesn’t think there is time for the revised rules to be adopted before Murphy leaves office in January. Message: I tried but I ran out of time. “This is just a convenient fig leaf for Governor Murphy to not tarnish his green reputation on his way to wherever else he’s going,” says Dillingham. (Murphy’s office declined to comment for this story.)

Others are trying to fill in the holes left by the lack of executive leadership on this issue. Amy Chester, of Rebuild by Design, a nonprofit launched after Hurricane Sandy to develop resilience-boosting solutions in the New York-New Jersey region, is pushing hard for New Jersey to adopt a $3 billion bond program to pay for planned adaptation projects that the state had hoped to fund with federal dollars. In a perfect world, she says, “by the time next March rolls around, communities would start being able to apply for that money.” But whether incoming Governor Mikie Sherrill will care about climate adaptation enough to spend political capital addressing it is unclear. During her campaign, Sherrill acknowledged that “New Jersey is one of the most flood-prone states in the nation” and pledged to bring together local, state, and federal stakeholders to “create a true statewide flood mitigation and resiliency plan.” (A representative for governor-elect Sherrill did not reply to a request for comment.)

In addition to worries about where the money is going to come from, and political resistance to constraining development in any way, there’s a psychic barrier at play: The prospect of a radically changed Jersey Shore is so alien and frightening that it barely registers. Nick Honachefsky, the Camp Osborn fisherman, says he lost everything in Sandy — “emotionally, mentally, physically” — but is confident he’ll be back. Kevin Wark, the fisherman, says “there’s going to be a day when people are going to really scratch their heads” trying to explain why they kept paying to stabilize the Jersey Shore. But he’s staying — even though the warming water and sand withdrawals off the Shore have just about ended his ability to make a living. “I just feel responsible to keep fishing,” he says.

For “the vast majority of people,” says Angarone, “not only can they not think about it, they’re not interested in imagining what the future looks like…. It’s hard to imagine that [the Shore is] not always going to be there.”

WHAT COULD THE JERSEY Shore become? In 2013, a federally funded competition asked participants to envision its future. One group of landscape architects, the Massachusetts-based firm Sasaki, imagined people visiting natural sanctuaries using trams, boats, and water taxis, but not, eventually, living there. “We had that idea of moving off the barrier island, which is a spit of sand that wants to move around with the waves that is so vulnerable,” says Jason Hellendrung, a landscape architect then with Sasaki and now with Tetra Tech. The plan also included building up “eco-hubs” in higher, drier inland places that could help expand tourism.

The architects imagined a future where visitors could still have the joy and recreation of the Shore without putting people’s livelihoods and lives at risk. The Sasaki group didn’t win the competition, and any strategy to move gradually away from the Jersey Shore seems unlikely.

The southernmost tip of Long Beach Island is a nature preserve that does not receive federal sand. It has drifted 100 feet closer to the mainland thanks to the natural movement of water and sand.

Rob Auermuller/Life on the Edge Drones

Blue Acres, a program in New Jersey aimed at helping people voluntarily relocate from risky areas, has bought out over 1,200 homes since 1995. But buyouts are not happening along the Shore — in many cases, property values are too high to match the program’s resources. Blue Acres can offer at most about $700,000 per home, while in Bay Head and Mantoloking alone this summer nearly 50 houses came on the market at a median list price of $3.2 million. People and politicians would rather muddle along.

Yet the cost of muddling along is very high and growing, as higher seas, increasing flooding, and destructive storms pummel the Jersey Shore. Back in Mantoloking, 90-year-old Haig Kasabach, Peter’s father, who served as New Jersey’s state geologist in the mid-1980s, looks around him at several very large clapboard houses sitting tall and gray inside ample lots, nestled behind bushes, new trees, pools, and green grass, all rimmed by white fencing. He’s wearing shorts and a large floppy hat. “I think the risk is too high down here,” he says. “I think people should be paying for their infrastructure, including the water system, the electrical system, the sewer system. To constantly rebuild it doesn’t make sense. At least using public money. If they want to do it with their private money, more power to ’em.”

“Where does it not make policy sense to continue spending public dollars?” asks Sean LaTourette. “That’s a hard decision.” We’re standing at the tip of Long Beach Boulevard in sight of a dozen new houses. “When you fly over this, and you see this development, the 10 houses on the other side — I wonder what my [14-year-old] kids will think when they are leaning into their retirement.” He pauses. “I think their reflection might be, ‘What the hell were people thinking?’”

Wealthy people with second homes along the Shore will be able to muddle along for the next few decades better than anyone else. Peter Kasabach points out that if public resources and services along the Shore evaporate, “at some point, if you end up having a place that is only vacation homes, then there’s no schoolchildren.” Which means local governments won’t have to worry about diminishing property taxes, because they won’t be funding public schools. Homeowners will self-insure and pay for their own emergency services. Their mindset will be, according to Kasabach, “If I am here for five years, and my house gets wiped out and I can’t have a beach house anymore, I’ll move somewhere else.”

For the last four years, Angela Andersen, who is also the sustainability coordinator for Long Beach Township, has been leading an effort to stabilize the 160 small eroding islands in the bay between Long Beach Township and the mainland, using bags of oyster shells and other materials. These islands are disappearing under pressure from waves and storms, and “time is not on our side,” she says. She knows how fierce the threat is. Like most people living along the Jersey Shore, though, or people with Jersey Shore memories, she’s hesitant to talk about what her town will look like in 2100. She doesn’t want to elevate her house, even though it took on six inches of water during Sandy. “I like my house the way that it is now,” Andersen says. “I don’t want to live up.” She adds, “Next storm, we’ll open the door, we’ll call it a day.”