Daniel Penny’s Deadly Chokehold Shocked the Country. Now, He’s Going on Trial For Manslaughter

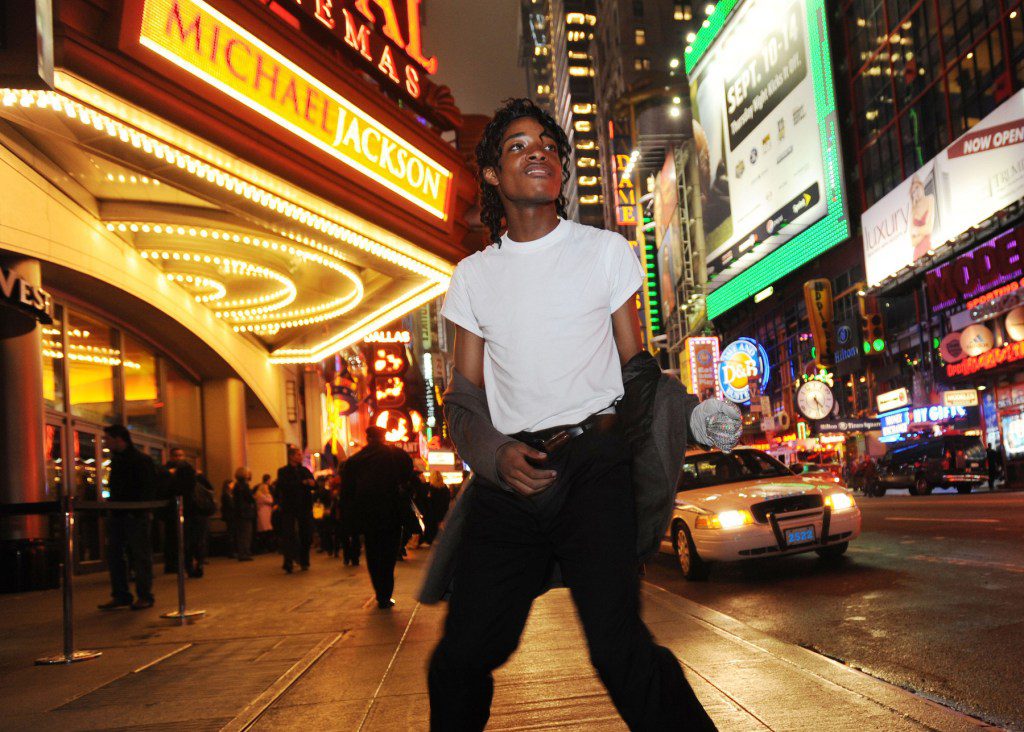

Sometime after 2 p.m. on May 1, 2023, Jordan Neely boarded a northbound F train in Manhattan at Second Ave. Neely, 30, was no stranger to the subway. For years, Neely performed as a Michael Jackson impersonator, both underground and at the tourist hub of Times Square, bringing whimsy to weary straphangers and pedestrians. Neely, 30, had even amassed fans outside of New York City. Neighbors described Neely as kind, chatting about video games and anime, but quiet. There were even times when Neely, who as a busker was not by any means cash flush, would give needy kids money for food and haircuts, they would tell The Guardian.

On that day, Neeley happened to enter a train car with a rider by the name of Daniel Penny. The then-24-year-old Marine veteran had boarded the train in Downtown Brooklyn shortly before 2 p.m. Penny, who was heading home from class, planned to exit at the Broadway-Lafayette station, and hit the gym. He wanted to go for a swim.

The car was crowded. At some point, according to court papers, Neely started yelling. What exactly he said remains a matter of dispute: Most passengers recounted that Neely remarked that he was homeless, hungry, and thirsty. Several claimed that Neely threw his jacket on the floor. Many said that Neely said he wanted to go to jail or prison. A handful said that Neely threatened to hurt others on the train. Some said that Neely didn’t say anything of the sort.

“For me, it was like another day typically in New York. That’s what I’m used to seeing. I wasn’t really looking at it if I was going to be threatened or anything to that nature, but it was a little different because, you know, you don’t really hear anybody saying anything like that,” one witness said.

“I’m from New York and I’ve been riding subways, buses all my life. I myself interacted, if not interacted, witnessed outbursts from people on the train, so I personally didn’t feel threatened by it . . . It was just common to me,” another recalled.

Recounted another: “[H]onestly, I wasn’t really worried about what was going on…I’m kind of used to that, so I see that all the time.”

The events that followed Neely’s outburst, which authorities said spanned a mere 30 seconds, wound up being anything but common. Penny approached Neely from behind, grabbed him around the neck, and pulled him to the floor. Penny’s back was against the ground, Neely’s back against his chest. Penny continued gripping him around the neck, and wrapped his legs around Neeley’s. Neely could not break free.

The train roared into Broadway-Lafayette station. Most riders in the car disembarked. But Penny kept restraining Neely. At some point, two other male passengers grabbed Neely’s arms, further thwarting his escape. Five minutes into Penny’s restraint, Neely stopped moving with any discernible purpose. One witness described Neely’s comportment as “twitching and the kind of agonal movement that you see around death.”

“If you don’t let him go now, you’re going to kill him,” one rider told Penny. After more than six minutes, Penny wriggled out from under Neely. Penny and one of the passengers rolled Neely’s limp body onto the side. A “thick and pinkish substance” spilled out of Neely’s mouth, according to court documents.

The police arrived several minutes later. Neely’s pulse was faint and he was not breathing. Police tried CPR to no avail: Neely was pronounced dead at a nearby hospital an hour later.

After more than one year, Penny is scheduled to stand trial on Oct. 21 on charges of second-degree manslaughter and criminally negligent homicide. These specific charges mean that Penny is not being tried for intentionally killing Neely. Prosecutors are arguing that Penny acted in a careless way which he should have known could have resulted in Neely’s death. They have pointed to his Marine training, which included discussion of the potential lethality of chokeholds, and the fact that he continued restraining Neely after he’d stopped moving. Penny, who has pleaded not guilty, insists that his actions were justified under the law, claiming that he had every reason to think Neely posed an imminent and potentially fatal threat. At the time, Neely’s death sparked a discourse on crime and disorder that resonated far outside of New York City. Many saw it as an indictment of a social-support system that routinely failed society’s most vulnerable, while others superimposed a narrative that it was justified vigilantism on the lawless streets of a liberal city. And as the country only becomes more politically fractured, it’s anyone’s guess how the trial will play out.

PENNY, FOR HIS PART, CHATTED openly about the incident with police. At first, Penny said, he wasn’t paying much mind to Neely. “He was just a crackhead,” Penny recalled in a statement to police, with whom he voluntarily spoke after the incident. Then, Penny claimed, Neely’s behavior took a turn, claiming he tossed a jacket at passengers. “He’s like, If I don’t get this, this, and this, I’m gonna, I could go to jail forever.’ He was talking gibberish, you know, but …I don’t know. These guys are pushing people in front of trains and stuff…” After this interview, Penny left the Fifth Precinct a free man. Cops who interacted with Penny described his demeanor as unencumbered. Video recordings of the encounter surfaced shortly thereafter, prompting public outcry. The medical examiner then deemed Neely’s cause of death “compression of neck (chokehold).” Penny was arrested on May 12, 2023.

According to New York, Neely had a history of trauma and unstable housing, coupled with ineffectively treated schizophrenia and addiction, which many believe set the stage for a senseless death. Many on the right viewed Penny as a red-blooded American man who justifiably defended himself and others from violent derangement. Top Republicans cast Penny as the true victim in an effort to hammer Democrats on crime. Without watching the video, Donald Trump said Penny “was in great danger and the other people in the car were in great danger.” The case also hearkened back to New York City’s troubling history with subway vigilantism, drawing comparisons to Bernie Goetz. (In 1987 Goetz, who is white, was acquitted of attempted murder charges after shooting four Black youth on a train several years prior.)

However politicized Penny’s case once was, it remains to be seen whether his trial will fuel partisan discourse as it unfurls in the shadow of the 2024 election. Yes, Trump does have a soft spot for vigilantism. But the Republican presidential hopeful has focused on migrants in his recent rants about violent crime — which is down under the Biden-Harris administration — claiming undocumented newcomers are bringing disorder to the United States. It’s also unclear how much voters will care about the motifs in Penny’s trial. Polling indicates that Americans are most concerned about the economy and migrant crisis. And Manhattan jurors – however frustrated they might be with worsening quality-of-life under indicted Mayor Eric Adams’ administration — might well consider the facts rather than social media noise.

Jordan Neely as a Michael Jackson impersonator in Times Square in 2009.

Andrew Savulich/New York Daily News/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

PENNY IS POISED TO USE a defense of justification, claiming that his restraint of Neely was legitimate and not criminal. In New York, a person can legally use physical force against another to defend themselves, or others, who are in immediate danger. Some witnesses who testified before the grand jury described feeling scared by Neely’s actions. A mother and son “shielded themselves” behind the boy’s stroller to protect themselves from Neely, Penny’s team wrote in court papers, citing grand jury witness testimony. Another passenger told grand jurors they felt they were “going to die.” A high-schooler placed her hands on a classmate’s chest and recalled “praying them doors would open.” Yet another claimed: “I have been riding the subway for many years. I have encountered many things, but nothing that put fear into me like that.” They will say that Neely had K2, a highly addictive synthetic cannabinoid that can cause aggression and psychosis, in his system — something prosecutors themselves plan on saying in court in discussing the medical examiner’s findings — and they’re asking a judge to let them introduce historic evidence of his history with K2 abuse and psychiatric records.

Prosecutors want to bar testimony from the witness who would discuss them, arguing in court papers that “a deceased victim’s prior bad acts and psychiatric history are not admissible unless they are relevant to an issue at trial.” More, they note, Penny couldn’t have known about this history when assessing whether Neely posed a grave threat. “The defense should not be permitted to introduce damaging background information regarding the victim’s character and history. The only reason to do so is to influence the jury to devalue Mr. Neely’s life,” prosecutors argued.

Penny’s lawyers insist that he could not have predicted that his actions could result in Neely’s death, and claim Penny didn’t mean to kill Neely. But prosecutors don’t have to prove intent with the counts Penny faces — they only have to prove that Penny “recklessly” caused the death of another person. And for that, they have statement after statement. “I just put him out. I just put him in a chokehold,” Penny told police. “He came on and he threw shit, he’s like I don’t give a shit, I’m going to go to prison for life and stuff, so I just came up behind him and put him in a chokehold. He was threatening everybody.”

“We just went to the ground. He was trying to roll up, I had him pretty good,” Penny told police. “I was in the Marine Corps”