America’s First Olympic Breakdancer Is Ready to Take Gold

V

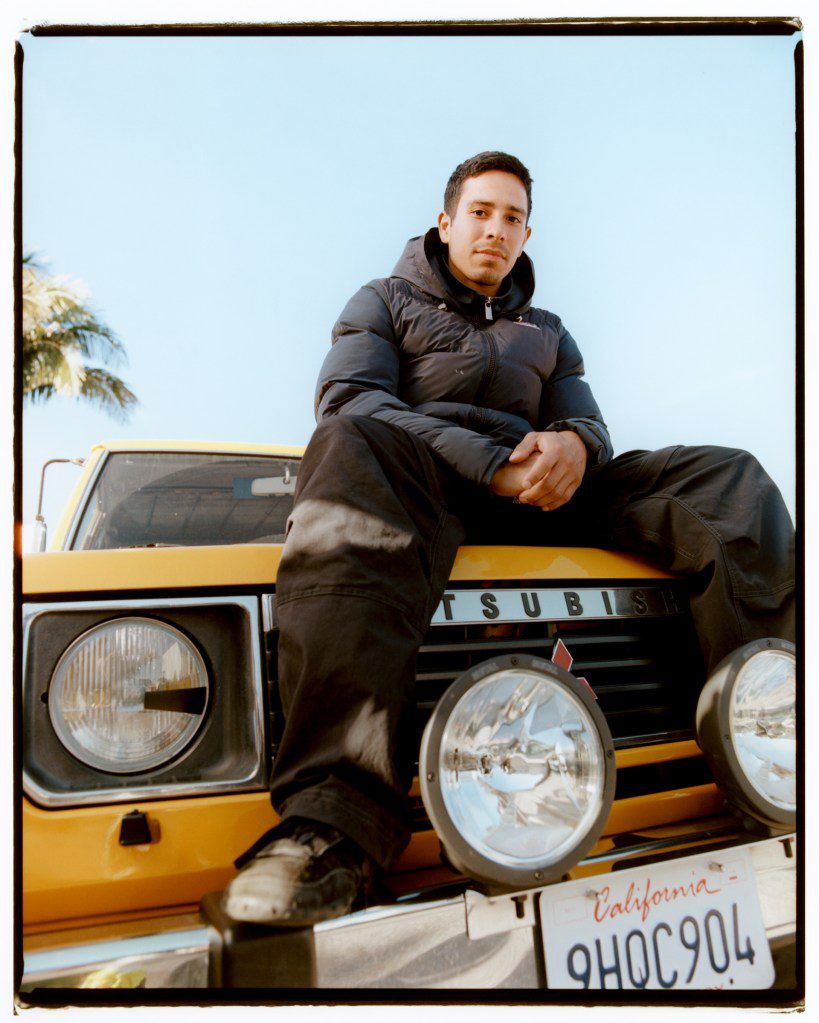

ICTOR MONTALVO DRIVES the most yellow vehicle in Los Angeles County, a 1987 Mitsubishi SUV he just purchased off of Craigslist. He pulls through the security gate at a sprawling Santa Monica office compound, parks, and removes a gold chain and ring he bought in India last year. The sunglasses stay on. Just back from Japan, he’s jet-lagged as hell. “I swear it’s not a hangover,” he says, chuckling. “Just feels that way.” But alas, he must train.

You’d probably call Montalvo a break dancer; they call themselves “breakers” and what they do “breaking.” The breaking world knows Montalvo as “B-Boy Victor” — they’re all B-boys and B-girls — and he’s one of the best that competitive breaking’s ever seen. He’s won every major breaking event that’s existed, most of them multiple times. When he won the World DanceSport Federation Breaking World Championships last September, that qualified him as the United States’ first-ever Olympic breaking representative.

The International Olympic Committee made the announcement in 2020: Breaking would be in the 2024 Paris Olympics, transforming what the sport means to the world and what’s possible for its breakers. “It’s fucking great,” says David “Kid David” Schreibman from Los Angeles, a 35-year-old breaking icon and commentator for Red Bull’s BC One competitions. “Because guys like Victor are making a living like I wish I could have.… That was my dream. We never got any of that. We had to be the fucking background dancers for Justin Bieber. Also cool, but not this cool.”

However, Montalvo will be 30 years old in Paris, the upper limit of breakers’ competitive prime. He’s concerned. “The kids now are crazy,” Montalvo says. “They’re like, flying. Incredible stamina. I’m not the same as when I was younger. I’m not as fast, as strong. Maybe more creative. But it’s getting tougher.”

“Breaking has to be one of the hardest things in the world,” Schreibman says. “You need the athleticism of a professional athlete, but you also need to be an artist, and you need to dance. It’s like asking Picasso to mountain climb. That’s what makes breaking so hard — that element of needing someone who’s creative, but also has the highest athletic ability.”

Hence the training, jet-lag be damned.

After lunch, Montalvo goes to a state-of-the-art gym with cutting-edge equipment, high ceilings, and walls that open like doors, letting in the beautiful Southern California weather. A trainer appears. The workout begins. He goes for an hour, mostly core work. He does it right. The final exercise requires Montalvo to assume a modified plank position by holding one end of a barbell elevated by a 45-pound plate on it; the other, empty end is secured at floor level. Montalvo rolls the barbell to his right, controlling his body down to a halt parallel with the floor, then he raises himself back up by pulling the barbell back beneath him. He repeats this to his left.

Over the next week, almost every day will see Montalvo train, do interviews and photo shoots, and dance for hours. Many nights end with beers and mezcal shots. He has endless energy, like a soul determined to make full use of its body.

He’s also quiet, humble, steady. “I have made it so far from where I started,” he says. “Gold is the last possible thing to achieve. And this is probably my only chance.”

Thing is, there was a point last year when Montalvo didn’t think he’d make the Olympics. “I thought I’d lost it,” he says, “wondering, ‘Do I still got it?’”

Not long before that, burned out and grieving a sudden loss, Montalvo nearly quit competitive breaking for good. Getting here meant facing that pain again by leaning on lessons imparted by the man whose death he grieved.

MONTALVO’S PATH TO the Olympics began in 1999, when he was six years old and his father, Victor Sr., and uncle Hector watched the 1984 movie Beat Street. Hollywood’s first motion picture about breaking, it featured Rock Steady Crew, the world’s first professional breaking group; they’d first appeared in the 1982 documentary Wild Style and the 1983 film Flashdance.

Years prior, in Puebla, Mexico, when Victor Sr. and Hector first saw those movies on Betamax tapes, it was like they were charismatics struck by the Holy Ghost, dropping to the floor to copy the dance moves. They formed a breaking crew, found jams, battled other breakers, and by the mid-Eighties, traveled around Mexico competing and dreaming of winning global competitions in breaking’s capital, New York City.

The scene quickly died out in Mexico, however, leaving Victor Sr. and Hector to sate their artistic passions by starting a heavy-metal band. In time they made a new home, near their mother in Kissimmee, Florida, where Victor Sr. worked as a cook.

Gold is the last possible thing to achieve. And this is my only chance.

But now, watching Beat Street with his son, he saw the music and dancing do the same thing to his boy it had once done to him, young Victor’s eyes glued wide to the screen. “You know,” his father said, “I used to do that, too.”

Then he did it again. He “mopped the floor” by popping up onto a shoulder with his head on the floor and his legs in the air and scooching along, and did a “windmill,” spinning on his back and shoulders with his legs whirling toward the sky. And then he spun on his head. Montalvo remembers watching captivated. “Then I tried to do them,” Montalvo recalls, “and I would just fall over. I just, like, threw myself. But I loved it.”

Around that time, breaking underwent what one breaker called “a seismic leap” when Red Bull put on its inaugural Lords of the Floor event in 2001. LOTF treated breakers like professional athletes, covering travel costs for crews from all over the world, providing masseuses for dancers between rounds, and handing out $4,000 in prize money, then more than any other event. One breaker at the time said, “[It was] the first time B-boys were treated like rock stars.”

By age 10, Montalvo “was obsessed,” spending days on end with his cousin in the driveway or bedroom, dancing and spinning on cardboard.

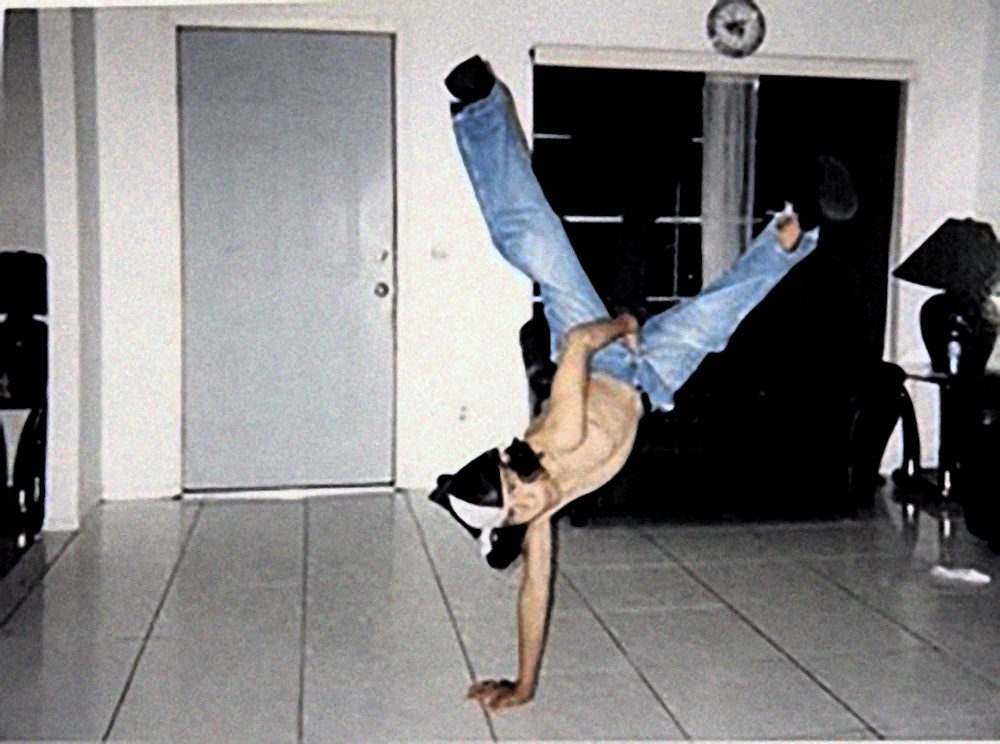

Breaking has four core elements. “Top rock” refers to movements while standing. “Part of top rock” includes footwork — self-explanatory. “Down rock” means moves done on the floor. “Freeze” is any moment when a breaker, well, freezes, usually while holding an unusual position. Down rock is the most crucial element, comprising myriad movements including spins, footwork, transitions, and power moves in which breakers spin their bodies on hands, elbows, shoulders, or their backs or heads. They can appear to defy gravity and the laws of physics, the result of extraordinary athleticism and strength. The most recognizable power move is probably the air flare, in which breakers spin while upside down and balancing on one arm.

The first move Montalvo mastered was the windmill. He remembers the exact moment, in his cousin’s bedroom, on a flattened cardboard box, when he got some momentum and launched himself to the floor on his shoulders and sent his legs flying in a circle. “It was the best feeling ever,” he says. “Like, ‘I got my first move.’”

Victor Sr. built his son a studio in the backyard, cobbling together money for supplies, then doing the labor himself with a friend’s help. Montalvo practically lived in it.

One day a teacher handed out paper apples with a question: What do you want to be when you grow up? Montalvo wrote, “The best B-Boy in the world.”

IN 2008, when Montalvo was 14, he went to his first major breaking event, Outbreak, in Orlando, organized by the legendary David “MexOne” Alvarado. “I saw so many breakers that were so different and original,” Montalvo says. “They just had this dope aura around them.”

He began sneaking out at night to go to jams with cousins and friends. “I knew they were sneaking out,” Victor Sr. says. “I just didn’t say anything. But I thought they were going to friends’ houses or something. I didn’t know sometimes they went to, like, freaking Miami.”

Montalvo begged his family for travel money, consumed by the sport. “Once we started going to events and watching people dance, I’m realizing, ‘Wow, I’m not that good,’” Montalvo says. “I need to go back and learn what they know. And from there, you start picking people’s brains. ‘How are you doing this?’ ‘How do you get this move?’ And you just learn the culture, the essence of the dance.… My mind started going ‘How did they get this way?’ And that’s when I got more curious about the culture side of the dance, and the roots of it.”

Some researchers put breaking’s roots centuries deep, dating back to warriors from the Angola region of Africa who performed similar dance movements as rituals to showcase agility, strength, and solidarity. Its modern evolution began in 1960s New York City, born out of the Bronx’s burgeoning hip-hop culture — not as sport but as art, a blend of dancing, gymnastics, and martial arts. People dance-battled to settle conflicts. “Literally, gangs showing up to another gang’s party,” Schreibman says, “and they would literally dance it out.”

They’d throw down with nothing between their skin and the street, art becoming scars. “People would get bald spots on their head,” Montalvo says, remembering videos his father showed him as a boy. “It was a pride thing.”

Nobody trained. Hell, most didn’t even stretch. And as Montalvo entered breaking culture, he found many still did it that way.

“Some people still want to keep it, like, real hip-hop,” Montalvo says. “Breaking on concrete. No stretching. No diet. Just get up and drink and smoke and break. And that’s how I used to be.”

AS A TEENAGER, Montalvo began developing his own style, flowing between air moves and freezes, relying on spontaneity more than choreography. He joined his first crew, the MF Kidz. “We would have these crazy all-day sessions,” he says. “We’d get high and just get lost in the moment, and that’s when we’d come up with just crazy shit. That’s when we’d get most of our signature moves.”

The music mattered as much as the dance moves, with the rapper Afrika Bambaataa and R&B-jazz-funk fusion group the Blackbyrds and the Godfather of Soul himself, James Brown, fueling young Montalvo’s long days and nights in the studio. He’d feel the music moving his body, often leaving him little say in the matter.

He found his signature move in 2012, at age 17, one he was the first to ever do — the Supa Montalvo: dropping into a crouch on one hand and spinning in 360s, an otherworldly feat of athleticism and strength.

“I didn’t know what the fuck I’d just done,” Montalvo says. He watched the video footage. “Like, the fuck? I just spun on my one hand three times?”

It was around then that Montalvo won the Red Bull BC One Cypher in Tampa, Florida. That earned him invitations to competitions abroad. To do that, however, and devote more time to professional competition, he would have to quit school.

His mother, Maria Guadalupe Montalvo, and Hector told him he couldn’t do it; Victor Sr. argued with them. “They are paying for the freaking plane tickets and the hotel,” he reasoned. “I don’t have money to give him that. They are going to make it so where he can travel to Europe. What the hell are you talking about he can’t do it?”

They had a point: The odds of making a living breaking weren’t good. Event winnings alone wouldn’t cut it — competitions rarely gave prizes above four figures. Some breakers like Schreibman eked out a living stringing together corporate gigs and Hollywood work. Many took other jobs to pay bills.

“He’s going to be a nobody,” said Hector.

“You know what?” Victor Sr. said. “Fuck you. It’s my son. It’s not your freaking son.”

Victor Sr. borrowed $500 from his father to get an expedited passport and to give his son some cash while abroad.

Montalvo asked his dad if he was sure this was right. “Hey, if something happens, and you don’t make it, then you don’t make it,” Victor Sr. said. “But follow your fucking dreams.”

BUT THE PATH WAS fraught. Once, a man claiming to be some sort of manager paid Montalvo’s way to El Salvador to judge a competition. “I shouldn’t have gone,” says Montalvo, who adds that the man ended up trying to manipulate him into giving up opportunities — while doing free work for him. “But it was a free chance to see more of the world.”

One trip to London ended as soon as Montalvo deplaned. He called his father in tears. Authorities had detained him in an airport holding cell for immigration-law violations after a misunderstanding over visa requirements. “I was so young, and they were so skeptical,” Montalvo says. “They were like, ‘Yo, what the hell are you doing coming here? You’re only 17. Your parents are letting you come here by yourself?’ And I didn’t have money.… I was in, like, immigration jail with people who’d been there for months and years.”

He’s hard to beat. He can flip, power, spin, footwork. He can do it all.

Montalvo often attended competitions with no way home without prize money. “I never really thought about it,” Montalvo says. “I didn’t really have a plan. I just loved the movement. The way it made me feel, it was like my own world that I could tap into. I loved always reinventing myself and winning, and never really thought about the money. I just loved the art of it. And the money came naturally.”

In 2013, at 18, Montalvo moved to Los Angeles. He stayed in a one-story home on Bundy Lane in Santa Monica, “the Bundy House.” It rented for $3,000. Twelve people split it. And the Bundy House, Montalvo says, “was crazy.” They all shared one bathroom and shower. And there were always guests. “People would just show up from Japan, Russia, Ukraine,” Montalvo says. “Like, ‘Yo, we come here to practice.’ Just sleeping on couches. But then it was like a whole jam back here. We’d start at midnight and go until, like, noon, smoking, drinking, hanging out, dancing.”

They were climbing a mountain as it formed. That year, the World DanceSport Federation held its first breaking world championships, further validating the sport.

Breaking’s fan base swelled. Events drew tens of thousands. Gyms filled. Livestreams pulled hundreds of thousands of viewers. Breakers began signing modest sponsorship deals.

After performing admirably, in 2014 Montalvo was invited to join Squadron, a one-of-a-kind bicoastal crew founded by Schreibman and Alvarado. “He’s an all-arounder,” says Luis “Luigi” Rosada, a 37-year-old Squadron member. “He’s really hard to beat. He can flip, power, spin, footwork. He can do it all. He’s a perfect recipe for competition.”

“There’s a level to Victor that’s super dangerous,” Schreibman says. “His pace. His efficiency with his energy. Compare it to boxing. Victor doesn’t do huge knockouts all the time. He’s great at jab, jab, jab, jab.”

The best competitive breakers find ways to surprise judges and opponents while remaining consistent, requiring a nearly-impossible balance between steady practice to refine and maintain one’s abilities, and forever reinventing oneself. “I just don’t think there’s another competitive breaker who is as consistent and has the full package and can deliver it the way he does,” Schreibman says.

But heartbreak conquers all. In 2015, breaking up with a longtime girlfriend left Montalvo feeling lost and depressed. Alvarado helped him course-correct, taking Montalvo to competitions by way of road trips, creating hours of conversation and mentorship.

An undocumented immigrant when he arrived to the States who later acquired his green card, Alvarado built Orlando’s breaking culture, grew Outbreak into a global series of significant events, and became one of breaking’s most iconic figures. Having grown up in the same area, and then taking him under his wing, nobody influenced Montalvo more. “He was telling me, ‘You’re going to be winning all of these amazing events, you’re going to be winning 20 grand here and 20 grand there,’” Montalvo says. He had his doubts. “That’s so much money,” he says. “I just didn’t see me breaking at that level.”

Alvarado argued otherwise. “He’s the one who told me what could happen,” Montalvo says. “He programmed me with this belief. ‘Dog, you’ve already done it once.’ I’ve beaten these people. ‘So you can do it again.’ And then everything he said was going to happen came into real life.”

Suddenly, Montalvo experienced success the likes of which no breaker ever had. “That year,” Rosada says, “he won everything.”

The Red Bull BC One America Finals in his home region of Orlando. The inaugural Silverback Open in Philadelphia and the largest single-event prize — $15,000 — in breaking. The Freestyle Session World Finals in California. Then came the Red Bull BC One World Final in Italy, where Montalvo won a world title, becoming what he wrote on that apple when he was 10, the best B-boy in the world.

“Breakers just don’t really go on winning streaks like that,” says Schreibman. “It’s so hard to put together back-to-back wins. But then this kid was winning everything.”

“This guy made over 100 grand off jams,” Rosada says. “This is the new thing. Vic was one of the first ones to do it.… [Alvarado] saw it with him.”

Montalvo gave his championship belt to his father; that made him cry. The belt still hangs in Victor Sr.’s bedroom.

IN 2016, MONTALVO MET Kate Pavlenko, “B-Girl Kate,” in New York. An athletic, blue-eyed, brown-haired breaker from Ukraine, she had won a number of regional events and held her own near the top of the ranks worldwide. They bonded over a shared love of jazz and funk music. They grabbed drinks, went dancing, and spent days on end together.

When Pavlenko visited Montalvo in Los Angeles, they escaped the cramped conditions in the house by sleeping in a boat parked in the driveway. Later that year, when Montalvo returned home to Kissimmee to visit family, she went with him. “I loved his heart,” she says. Much like Montalvo, Pavlenko speaks with a calm warmth, smiling often and choosing her words carefully. “He is a very kind person, and very easygoing. It felt easy to communicate with him, even though English is not my first language. I thought we were going to have a language barrier, but we didn’t.”

In August 2017, Montalvo and Pavlenko went on a road trip with Alvarado from Florida to Tennessee. “We were talking, he was on the phone watching Superbad, just laughing like crazy,” Montalvo says.

A month later, Montalvo woke up to the news that Alvarado had passed away. Montalvo had just seen his friend a few weeks before — telling me about this loss, he has few words for it, like he still feels the heartbreak. “It was just so shocking,” he says, shaking his head.

MONTALVO FINISHED 2017 as the top breaker in the world again, but losing Alvarado hit hard, and competitive breaking’s relentless grind got old. “Everyone knows me and knows my moves and what I can do,” he recalls. “I used to never practice for competition. I just did it because I loved it. Now I’m practicing for competition instead of just dancing and enjoying. It was getting exhausting.”

“It’s rough,” says Schreibman. “Every other weekend, you’re in an arena, and a guy’s standing 100 feet away from you, and he’s gonna do the same moves you saw last weekend, the music’s gonna be the same as the weekend before.”

How many times can you become a new you?

Creating further strain: Montalvo had become a full-fledged global celebrity in the breaking world, now with hordes of fans. A 2018 China visit left him disturbed when a group of breaking fans manhandled him as he left an event. “Grabbing me like I was a piece of meat,” he says.

Then Covid hit, forcing a break from everything. He went hiking, mountain biking, snowboarding, surfing. He moved back home to Kissimmee, bought a house, and renovated it with his dad and family. Being back home felt good. But he missed Pavlenko, who was locked down in Ukraine. As soon as he could travel, he went there for four months. They traveled Russia together. He trained in muay thai and boxing. He mulled following the well-trod path of breakers past: go Hollywood, work music videos, commercials, movie deals, background dancing gigs, that sort of thing. It was viable.

“I’ve been doing it for 20 years,” he says. “I was definitely just over it … was like, ‘I’m doing the Hollywood thing.’”

Then came news from the International Olympic Committee that breaking would be included in the 2024 Paris Olympics.

One hell of a plot twist.

“I’d never really watched the Olympics,” Montalvo says, “other than 2012, London, watching Usain Bolt.”

But he could see it now. The opening ceremonies, the global stage, medals around necks, a gold one around his. Sponsors connected him with Olympians past who shared the pride of representing home and country to the world, and taught him what opportunities awaited after a podium. “That inspired me,” Montalvo says. “I said, ‘OK, this makes it interesting again.’”

RETURNING TO COMPETITION went well enough at first, so well that Montalvo again won the Red Bull BC One World Finals in 2022, claiming another belt. Through the first half of 2023, however, Montalvo entered three separate Olympic-qualifying events, and finished in third place each time. Doubt arose. “I didn’t know if I could make it,” he says. “I gave myself all this pressure.”

Going into the World DanceSport Federation Breaking World Championships in Belgium, one of the last remaining Olympic-qualifying events, Montalvo had a near nervous breakdown. Everything felt off.

Montalvo remembered Alvarado. “I told myself what he would’ve told me,” Montalvo says. “‘Dog, you won so many countless events, international events. You did it all before. You can do it again.’”

Montalvo and Pavlenko ran to a store to get what he liked — flat, white skater-style Adidas — but they didn’t have his size. On their way out of the store, Pavlenko saw a mannequin wearing the shoes Montalvo wanted, but they were a size-and-a-half larger than Montalvo normally wore.

“She forced me to put ’em on,” Montalvo says. But when he put on the bigger shoes they felt good. “Ended up being the perfect size.”

Montalvo became … not like his old self, exactly, but a new version, reinvented once again. Maybe he couldn’t get high before the competition, but he found that place in his mind, letting go and dropping into the moment, opening his body to go where the music led.

He felt good. This carried him through round after round until the final competition scores were announced, and Montalvo had claimed the title and his spot in this summer’s games in Paris.

Montalvo remembered being 10 years old and spending all day in a backyard studio, when the Olympics were never even a thought, a dream beyond a dream.

“I think I’ve surprised myself,” he says. “I’m like, ‘Damn, I can’t believe I’ve been able to do this.’”

IT WILL HAPPEN AT Place de la Concorde on the Champs-Élysées. Montalvo will be one of two B-boys representing the United States through 16 rounds of one-on-one competition over two days. Day One will be a round-robin tournament, by the end of which eight will remain. Day Two will unfold in a seeded tournament format, culminating in breaking’s first Olympic medals.

For those who’ve come before Montalvo, this moment brings mixed emotions.

“I’m low-key kinda jealous,” says Rosada. “I’ve definitely had my bitter moments about it. I put in all this work, and this younger generation is reaping the benefits of it.”

Then there’s the diluted nature of Olympic competition. It will all be one-on-one, with little reflection of breaking’s rich history of crew battles, let alone its origins in hip-hop culture. That’s another thing: Public competitions can’t use popular hip-hop music without paying expensive licensing fees, and the Olympics won’t confirm whether or not they’ll splash out for them. There’s a chance the competitions will be held using stock beats.

“That’s one of the hardest things,” Montalvo says. “We fell in love with the dancing because we fell in love with the music. But when we compete we don’t have the music we fell in love with, that made us dance at first.”

“Some of the heart and soul is gone,” Schreibman says. “My fear is that people are going to see a bunch of people onstage dancing to mechanical music and think that’s breaking, and that’s not what’s really awesome about this culture.… That’s the counterculture side people don’t see unless they go out and see it.

“The hours in the garage with your friends, playing these classic hip-hop records, creating movement that started in your brain and now it’s in the world in raw form. That’s what makes breaking beautiful.”

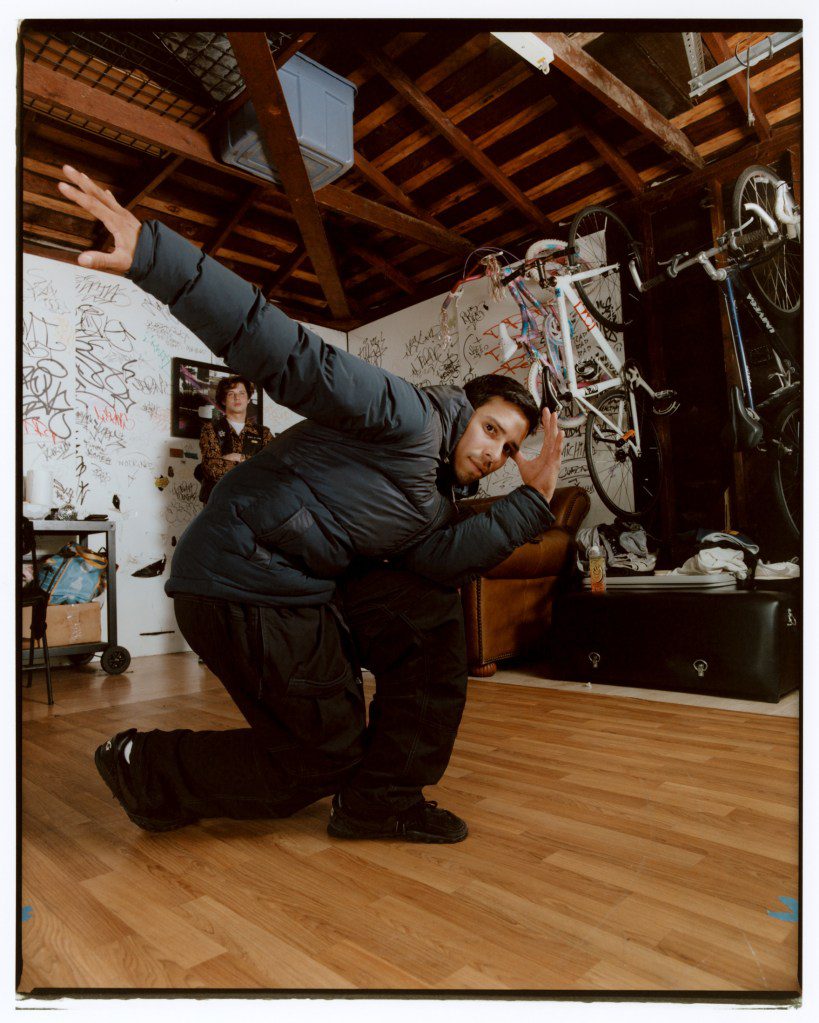

Montalvo agrees. He invites me to the Bundy House.

I PULL UP TO the curb behind the yellow SUV and meet Montalvo in the driveway. The boat’s still right there. Beyond, a gate; beyond that, an open garage. Graffiti covers the garage walls, along with signatures from countless visitors who’ve passed through. A couch and chairs line the walls; the middle stays clear, covered by padded flooring. Jose “Seize” Rivera spins R&B and funk records and smokes a spliff; he wears a black vest repping the crew he was born into back in the Bronx, the Mighty Zulu Kingz. David “Illy” Bennett, an MF Kidz founding member, now an actor and model who still performs with the L.A. Breakers on Venice Beach, breaks in slow, smooth moves. A dozen other people mingle throughout the garage and backyard, smoking and drinking.

Montalvo has his own place now, including a garage, but he still comes here most days.

He sheds his coat and jewelry and checks the laces on his shoes. Same ones he wore to win worlds and make the Olympics. Then he takes his turn. He eases in with some light footwork and bobbing of the head and shoulders, like a boxer getting loose, then he moves. A windmill. A freeze with his legs in a position akin to a soccer kick. A Supa Montalvo. He stops after a couple of minutes. There’s light clapping. A toddler high-fives him.

Soon Pavlenko arrives, wearing baggy gray sweats and a navy hoodie. She pulls her hair back into a ponytail and gets in the mix.

People of all ages flow in and out of the center, moving with the rhythms of the hip-hop tracks thumping through the speakers. The toddler attempts imitation, to moderate success but much fanfare. “That’s it right there, baby,” Montalvo says. “That’s how it starts!”

This goes on for hours. Dancing, drinking, smoking, gassing each other up. It’s the breaking version of sandlot baseball, of pickup hoops at the park, of a day at the beach with a board and good break. Then it’s time to hit a nearby dive bar for dinner, darts, and pool, and a nine percent Belgian beer called Delirium Tremens, then shots of mezcal.

The next few days with Montalvo unfold in kind. Training, Bundy House breaking, drinks with friends. A quiet happy hour at the Misfit in Santa Monica turns into mezcal-fueled competition at another bar with shuffleboard and Pop-A-Shot and claw machines.

A trip to a club ends with a bouncer refusing entry. Something about dress codes and Victor’s oversize breaking pants. We’ve had enough mezcal that this could become a somewhat dramatic situation; the bouncer seems to sense this, perhaps invite it. Montalvo laughs. We hit another bar. When everyone else calls it a night, Montalvo wants to keep going. We make for Venice, where we close down the Brig.

“You ever get tired?” I ask.

He laughs.

“I am now,” he says, but he doesn’t mean the night. Every day’s a new interview, photo shoot, TV spot to film.

“It’s good,” he says. “But not really my thing. I’m ready to focus on just dancing again. That’s all what it’s about. I don’t really care about money or people knowing me or things like this. It’s about the people, the culture, the dance, you know?

“It’s about that garage.”

Production Credits

Photographic assistance: MARIA ROMERO. Lighting Technician: MIABELLA CHAVEZ.