A Tropical Island, a Chocolatier, and a Brutal Double Murder — Who Killed the Hollywood Expats?

T

he Caribbean island of Dominica is a kind of thorny paradise — a land of jewel-toned flowers and lush foliage that’s a refuge for sunburned foreigners looking to avail themselves of the waterfalls and hot springs, not to mention lucrative tax shelters. Woven through the tropical escapism is a darker past — a history of slavery and upheaval that has shaped the island just as much as the lapping azure waves. And most recently, a brutal double homicide has ripped through the small country, shaking the expat community and locals alike. Wild accusations of corruption, cartel involvement, faked deaths, and revenge have followed the crime, exposing the island to international scrutiny and roiling long-simmering tensions within.

By all accounts, when Canadian special-effects guru Daniel Langlois and his partner, Dominique Marchand, washed ashore in the late Nineties, all they saw was the beauty — the possibility. The wealthy couple celebrated their move by opening a tony hotel, yes, but also by giving back to the islanders who had welcomed them with open arms. Which is why when they failed to show up at their storied eco-resort Coulibri Ridge one day in early December 2023, their friends and employees were beside themselves.

Céline Caisse, Marchand’s old friend from Canada, was the first to realize something was amiss. The now-former general manager of Coulibri Ridge, Caisse would usually meet up with Marchand at the sun-soaked resort restaurant to evaluate the service while watching the palm trees sway above the blue sea. That Friday, though, Marchand was a no-show; Caisse also noticed that Langlois’ car wasn’t in the driveway.

Caisse checked in at the front desk to see if anyone had seen the couple, but the woman manning it hadn’t seen them all day. “Céline, it’s not normal,” Caisee recalls her saying. “Dominique would never miss a lunch with you. Something’s happened.”

Meanwhile, Langlois’ friend Simon Walsh — a local scuba-shop owner — was just pulling out of his driveway when a friend called to see if he was OK. Confused, Walsh asked what was up. There’s a car a quarter mile from your house, his friend said. There’s two bodies in it. And it’s on fire.

Soon, the news broke: The bodies belonged to Langlois and Marchand, and they had been shot before the car was incinerated. “The first time I’ve ever been scared in my life in Dominica was the night after that incident,” Walsh says now, watching kids frolic in the surf from the yard of his scuba shop as roosters crow in the background. “One of my concerns when this happened was that the community that they loved, that they chose to spend the last 30 years of their life in, was going to be so badly damaged by the news.”

On a small island where, until recent years, the homicide rate was relatively low, the murders sowed both terror and confusion. Who would kill the popular couple? And after the subsequent arrest of American businessman Jonathan Lehrer, whom Langlois had been warring with over a local road, the question became: Could the motive possibly be something as simple as a fight over real estate?

Rolling Stone spent the past six months talking to those close to both Lehrer and Langlois to find out how Lehrer lived, how Langlois died — and just how these wealthy expats, whose lives could have been a lost season of White Lotus, became embroiled in a case that involves two murders and Lehrer and his alleged accomplice on trial for their lives.

‘Daniel Was the Pixie Dust’

It was a moment that changed film forever: A Jeep full of scientists rendered speechless as a graceful brontosaurus loped into view. Audiences of the 1993 hit, Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park, were gobsmacked. It was history exhumed and reanimated.

“That was that,” says Steven “Spaz” Williams, a motor-mouthed special-effects artist with a penchant for military duds. “Spielberg saw it, and everything changed.” Williams created the dinosaurs using a mixture of models and computer technology, but credits that seismic shift to Daniel Langlois and his company SoftImage, which made those celluloid lizards look like the real deal instead of dated puppets. “We could not have done Jurassic without SoftImage. It was a revolution,” Williams adds. “They call me a visionary, but he was the original.”

L to R: Daniel Langlois, Pierre Lachapelle, Philippe Bergeron, and Pierre Robidoux.

Philippe Bergeron

A visionary, a modern-day Medici, a superstar — Langlois collected his share of honorifics over the decades he spent in both the realms of computer technology and philanthropy. The son of chicken farmers, Langlois was born in 1957 and grew up in the Quebec suburbs, and after working in the film industry for nearly a decade, he and a cadre of pals took the first steps toward Jurassic Park in a tiny, 10-by-12 office at the University of Montreal.

Although Langlois would grow into a slightly imposing figure with heavy brows and a penchant for dressing in all black, at the time he was in his mid-twenties and a bit goofy-looking, favoring scuffed shoes and wrinkled dress shirts. Along with University of Montreal student Philippe Bergeron and friends Pierre Lachapelle and Pierre Robidoux, the rag-tag crew set out to make one of the earliest computer-generated films, the 1985 short Tony de Peltrie. The story of a piano man recalling his glory days, by today’s standards it’s a simple affair featuring a mawkish-looking Tony tickling the ivories, but back then, it was a marvel.

“Daniel was the soul man,” Bergeron says. “He was the creative guy first and foremost, and that’s what made Tony [de Peltrie] alive. The technology? We were great. We were really good. But Daniel was the pixie dust.”

The short sent shockwaves through the industry. Trips around the world followed for Bergeron, including helicopter rides and fancy Monte Carlo hotels, but Langlois opted to stay home and work. That was a common refrain with him. “I don’t have visuals of him and I laughing and having a beer,” Bergeron says. “I do have wonderful memories of us in my kitchen, creating the storyboard and being geniuses.”

While Bergeron was jetsetting, Langlois was on to the next frontier. He founded 3D animation company SoftImage in 1986, which made him very rich when he sold it to Microsoft in 1994 for millions. By then, he’d met and fallen in love with Dominique Marchand, a gorgeous businesswoman and SoftImage employee with a drive that had distinguished her since high school, where she met close friend and future employee Céline Caisse. She was fun, though — Caisse recalls that in college, Marchand usually had an empty fridge, but she always had a bottle of champagne.

Together, Marchand and Langlois funneled money from the SoftImage sale into pet projects and philanthropy. In 1996, they funded the Montreal International Festival of Cinema and New Media, with Langlois telling the press, rather bluntly: “This is not a project that will be profitable.… I feel I got a lot from the film industry, and helping creative people express themselves will stimulate me as well. I get bored.”

As his businesses grew, so did Langlois’ network — although most of the folks I talked to considered him more of a benefactor and mentor than a friend. He and Marchand were generous — but insular. (Still grieving, the families declined to be interviewed for this story.) Nevertheless, the pair made an impact. Former employee Paolo Oliveira remembers an incident back in 1998, when they were adding an extension to a cinema complex Langlois ran. Langlois asked Oliveira to gather up their neighbors and organize a full brunch, at which he told the 20 people in attendance that he would foot the bill to renovate their buildings’ facades.

“He always taught me that you have to make sure that you have a good relationship with your neighbors,” Oliveira says. “Because even though you don’t live in the same house with them, you live with them.”

That statement would take on a kind of sad resonance in the years to come when a battle between neighbors — if police are to be believed — allegedly turned deadly.

‘It Was More Than the Road’

Kitted out in wetsuits and scuba masks, Daniel Langlois and Dominique Marchand plunged into the temperate waters of Dominica, an island nation studded with waterfalls, rainforests, and hot springs. The water was clear, boasting burgeoning reefs and deep dropoffs, sea sponges standing tall like Dr. Seussian skyscrapers as fish, seahorses, and otters coasted on the waves.

It was the late Nineties and Simon Walsh, the scuba-shop owner, had just met the couple, who would soon become the island’s newest residents. Langlois and Marchand acquired Coulibri Ridge, an old plantation dating back to the 1700s that they planned to turn into an eco-resort that would employ solar power and water filtration in order to be totally self-sustainable. Decades in the making, the resort now resembles a cliffside made of LEGO and blue glass, cutting a striking figure against the island’s greenery.

Daniel Langlois and Dominique Marchand

Courtesy of Céline Caisse

Langlois and Marchand were, as usual, all about business and helping their community out. After Hurricane Maria decimated the island in 2017, they rebuilt the primary school — as well as a local jetty. And when Walsh lost his home in the storm, Langlois took him in, later teaming up with the scuba-shop owner to set up a branch of his charitable foundation called Resilient Dominica to run food, water, and medicine to the island. “He wanted to deliver for humanity,” Walsh says, voice quavering.

There was one nearby family that Langlois seemingly failed to enchant, however: Jonathan Lehrer and his wife, Victoria, the former a serial entrepreneur who bought the neighboring chocolate plantation Bois Cotlette in 2011. Although both were enterprising foreigners — and owners of two of the island’s oldest estates — the men clashed nearly immediately over access to a track that ran through both of their properties.

The small path didn’t have a name back in the 1770s when it first appeared on a map, but the road that winds through Bois Cotlette and Coulibri Ridge has been worn down by countless feet. In fact, it used to be a minor thoroughfare, with archeological evidence of houses running alongside it and a ramshackle rum bar at one of the intersections. Hundreds of years ago, that road would have been walked by slaves and slave owners alike, as it was the one track that connected all of the estates to the wharf where the ships would come in.

Dating back to 3,000 B.C., Dominica was inhabited by indigenous people, per a history of the island by local author Lennox Honychurch. The first Europeans arrived in 1493, when Columbus bushwhacked onto the island’s shores. It was a thriving island even then, with thousands of years of history and its own culture — still, Columbus claimed it all the same, dubbing it “Dominica” in honor of the Lord’s Day.

The country remained in flux for centuries, with local tribes retaining control for a spell after Columbus’ arrival, until French settlers began colonizing in the 18th century. The British soon wrestled away control, though in the late 1700s. Slaves from West Africa soon followed, and plantations built on their backs began cropping up all over the island — including Bois Cotlette and Coulibri Ridge. The French and British continued to war over the land for years before the slaves were emancipated in 1834. (The island finally gained its independence from England in 1978.)

Still, many folks continued to work on the plantations, which began producing limes and cocoa at the turn of the 20th century. By then, though, the plantations became their own little enclaves, and the status of roads like the one running through Lehrer’s property became hazier as fewer people traversed them every day.

These days, that path is known as Morne Rouge Road, and it’s been the focus of a yearslong legal battle between Lehrer and Langlois. When the dispute started is murky, but Victoria Lehrer claims that the two families were cordial, if not distant, at first.

“When we first moved to Dominica, Daniel invited John to his property. They were people of education and status close to ourselves,” she says. “I was very interested in becoming friends or acquaintances. They were never outwardly friendly to us — or to me, anyway. But it was never outwardly aggressive.”

Around 2014, though, the two men started clashing over use of Morne Rouge Road, which Lehrer claims wasn’t built to withstand the tread of heavy machinery and tour buses; Lehrer’s family sent me a video of a work truck clipping the ruins surrounding the estate in 2016. For his part, Lehrer got approval that year to create two road diversions so that folks could bypass his estate more easily — one that was completed following Hurricane Maria in 2018, and one that a publicist for the family says Lehrer built after Langlois questioned the safety of the first section. The second path opened that same year.

Court documents filed by Langlois’ attorneys outline the reported shortcomings of the first road — and allege that Lehrer frequently blocked Morne Rouge to impede access to Langlois’ estate. Lehrer’s publicist rejects that claim out of hand: “Jonathan did not ‘block access’ by putting boulders and digging a trench — the trench was dug to erect a new sign and diverter to showcase the new road diversion,” he tells Rolling Stone in an email.

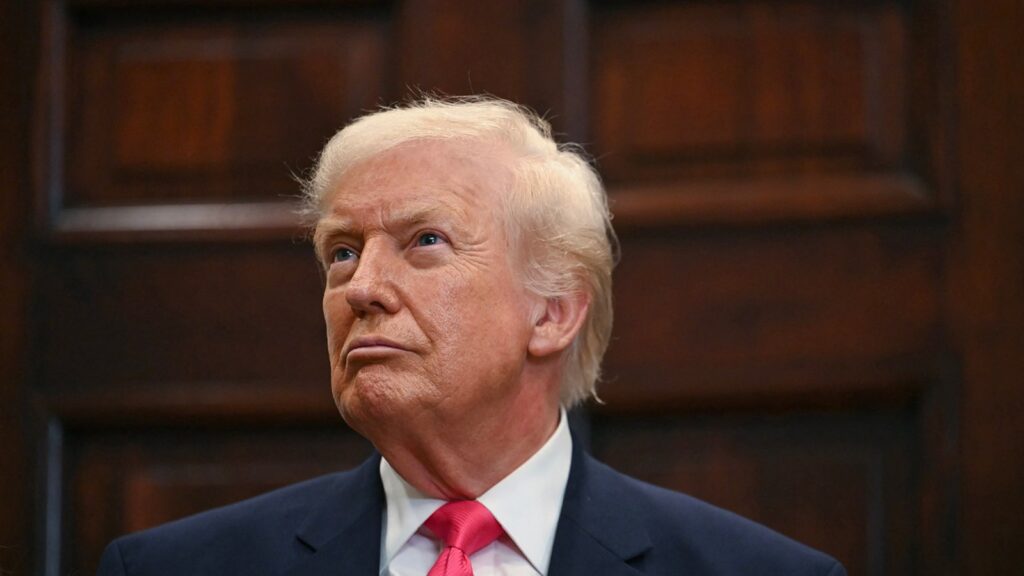

Jonathan Lehrer

Courtesy of the Lehrer Family

Regardless, the Canadian businessman began soliciting the government to classify the road as public in 2017, and went on to take legal action in 2018. Attorneys for Lehrer claimed that the road was not, in fact, public, alleging that ownership of Morne Rogue had reverted to him since the government hadn’t actively been maintaining it (an assertion lawyers contested in court documents).

The conflict simmered on for a year more, with some claiming that the Lehrers lashed out at Langlois and his friends. “They were yelling at us, ‘You are on our road!’” Marchand’s friend Céline Caisse says. “And after that, they had dogs. A lot of people [used the road] to go to work, and they stopped doing it because the dogs were chasing people. They were really not nice to people.”

Caisse says Victoria was actually the more aggressive of the two, although Jonathan wasn’t that much better, she claims. “It got worse and worse and worse,” she says. “I stopped talking to Jonathan because he was saying nonsense. But I also think he was jealous of Daniel. He would say, ‘I’m the richest man on the island; it’s not Daniel Langlois.’ Daniel would never say anything like that. It became a small problem, and then it became a bigger problem. It was more than the road.”

Lehrer’s PR denies Caisse’s allegations. “There has never been any evidence of dogs chasing anyone, as they were kept by the house during the day and used as an ‘alarm’ at night, as the site had been robbed on several occasions,” he tells me. As for Lehrer’s alleged boast, the PR says, “Jonathan barely knew Daniel; he was never a topic of discussion amongst the Lehrers, unless it was about the ongoing case that Daniel himself brought against Jonathan. Jonathan was never jealous of Daniel and cared nothing about the ‘limelight’ or being a celebrity.”

Lehrer himself claims that he wasn’t that bothered by the whole road incident — even after Langlois got an initial injunction in 2019 and the case effectively stalled out for a time. “I never even lost a half a wink of sleep,” says Lehrer, who spoke to me via his publicist and lawyer. “I believe that Langlois’ strategy was to just overwhelm me with paperwork. I don’t think he realized that I had the wherewithal to put a proper defense together. And it did take a little time, but [it wasn’t] a big deal.”

Still, the whole ordeal takes on a kind of resonance when you consider the history of the island — at least according to archaeologist Khadene Harris, who did research at Bois Cotlette as a grad student at Northwestern University after Lehrer acquired the property. “You’re both foreign white men, who, because of your wealth, were able to purchase these former plantations, which are connected to Dominica’s economic struggles since the post-emancipation period,” she says. “To see this dispute over property, over essentially former slave labor camps — it’s a wild transformation that’s both surprising and unsurprising. Unsurprising in the sense that a lot of the Caribbean is having to make these economic decisions that are kind of neo-colonial.”

Dominica, for one, has gone all-in on the Citizen by Investment Program, whereby folks can essentially purchase a passport by funneling money into local projects. The Lehrer family got their own passports that way, and are currently part of the program, offering citizenship to those who invest in the estate. Their website reads, rather ominously: “If the outside world has a major disruption, whether it be political, economic, prolonged natural disaster, or for a variety of other reasons shuts down tomorrow, 150 savvy investors will always have a safe haven and the ability to live peacefully at Bois Cotlette.”

Dominica’s Golden Passport program has had its share of issues, with the Government Accountability Project (GAP) alleging that the island has sold citizenship to such unsavory figures as an Afghan spy, a Turkish millionaire-fraudster, and a former Libyan colonel under Muammar Gaddafi. These programs are not supposed to work in favor of criminals, to state the obvious.

At the time the GAP report was being put together, Prime Minister Roosevelt Skerrit said in a presser: “We have professed to have a robust system that we go through in different layers of due diligence, and if somebody were to become a citizen of today and tomorrow morning the person goes and does something and finds himself in problem with the law, you can’t blame the program for that.” He also called reporters behind the report “terrorists.” (He didn’t respond to a request for further comment.)

Journalist Zack Kopplin, who was instrumental in compiling the GAP report, stresses how important the program is to Dominica’s health as a country — and how much power it wields. “Citizenship by investment brings Dominica’s government, and politicians, millions, if not billions of dollars,” he tells me. “To become a broker in Dominica’s citizenship by investment program requires deep connections to the island’s government.” (Kopplin has written for Rolling Stone in the past.)

Lehrer has not been connected to any shady dealings with regard to the program, but his involvement has raised a few eyebrows — especially since Lehrer’s lawyer, Lawrence Lennox, was previously attorney general of Dominica.

At a press conference, Lennox was asked directly about any unfair advantage Lehrer might have as someone with ties to the government: “That does not give us any advantage whatsoever,” he said. “We have a system of separation of powers just like you have in the United States and in Canada. The executive is totally different from the legislature.”

That connection certainly didn’t protect Lehrer on Dec. 1, when the police showed up at his door.

‘This Is My Castle’

News of the murders and Lehrer’s arrest filtered from the island to the States like a particularly random game of MadLibs: “American Chocolatier Arrested in Murder of VFX Pioneer” was the common gist. Nearly every outlet seemed to outline the road dispute as a motive for the alleged crime. The truth, though, is murkier than all of that — or at least according to Lehrer.

For one, he isn’t a chocolatier, per se — at least not in the Willy Wonka sense. If you ask anyone in that community (yes, there’s a chocolate community), he’s no household name. In fact, after the murders, the chocolatier group chats exploded with folks confused by Lehrer’s designation as a kingpin. “Lehrer has never been really a participant [in the community],” says Jose Lopez Ganem, Innovation and Outreach director of the Fine Cacao and Chocolate Institute. “He is basically a solo player.”

That’s because Lehrer’s not particularly serious about the art of chocolate-making. He’s simply a businessman with a penchant for novel experiences who purchased an old chocolate plantation on the island in 2011. It was meant to be a tourist destination first, with chocolate-making demonstrations added on for original flair — a new career for Lehrer after decades spent working the markets and corporate America.

Remnants of sugar processing production, Bois Cotlette Plantation, Morne Plat Pays, Saint Mark Parish, Dominica, Lesser Antilles, Caribbean.

Alamy

Lehrer grew up in Short Hills, New Jersey, an uber-rich suburb that boasts million-dollar homes and highly ranked schools — and he was a star. His dark eyes and thick mop of brown hair crop up more than once in the archives of the local paper, toting his ranking on the dean’s list, honor roll, and inclusion on a list of “Who’s Who Among American High School Students.”

Businessman David Bier was also on that list, a former classmate who lived not far from the Lehrer family. Bier’s family had less money than Jonathan’s, and the richer boy would often give him hand-me-downs. “He was an independent thinker,” Bier tells me. “I never had any sense of any criminality or anything, but he was quite inquisitive, into financial puzzles.”

Lehrer’s senior quote speaks to a kind of devil-may-care boyishness. “Good evening officer can I help you?” it reads. “Is [sic] fun in the sun it’s fun if you like it — but be CARFULL.” Still, his business acumen ran deep — according to Lehrer. He and his dad started their own venture when he was still a teen, importing beer from China to Chinatowns in the U.S.

To hear his wife, Victoria, tell it, after Lehrer transferred to the University of Pennsylvania in 1985, he spent the summer of 1987 interning as an options trader in Chicago. Nicknamed “Spu-man” — after the three-letter floor-access trading badge he wore on his orange vest — he hit it big on Black Monday, Lehrer claims, raking in millions in his early twenties.

Lehrer was so amped on trading that he missed the fall of senior year, but after his grandmother said she wouldn’t respect him if he didn’t get a college education, he headed back to school. He graduated in 1988 but managed to go into debt over the ensuing years — $200,000 in the hole, according to Victoria. Racecars, planes, motorcycles, and other boys’ toys tend to drain the bank account. Plus, he was fond of larks — like sending a lackey on a plane to the Caribbean to pick up fresh conch for him and his buddies.

Humbled and deep in debt, Lehrer got a job as a temp at MetLife in New York, where he met Victoria Dukat, his future wife. “I remember when we first met, he was like, ‘You’re my queen, and one day I’m gonna buy you a castle,’” Victoria tells me. A blonde spitfire from Brooklyn, Victoria fell in love fast, going on to marry and have four children with Lehrer. Meanwhile, Lehrer continued climbing the ranks at MetLife, becoming a VP around 2007, per Victoria.

The family continued to grow and so did their bank account. “We were so financially set we could have retired,” Victoria says. “Or we could take that money and we could invest and do something.”

Lehrer had dabbled in other businesses in the past, but after he stumbled upon Bois Cotlette during a business trip, he had his new white whale. “When we saw Bois Cotlette, I’m like, ‘Oh, my God, is this my castle,’” Victoria says, recalling what Lehrer told her when they first met. “He turned this desolate piece of rock and broken-up buildings into one of the premier destinations on Dominica. He has the Midas touch. It doesn’t matter what he touches, it turns to gold.”

His daughter, Emma, now 24, was equally thrilled. “They go, ‘We’re going to move to the Caribbean and be chocolatiers,’” she tells me. “And we were like, ‘Oh, my God! We’re gonna be eating chocolate all day. This is crazy.’ We told all our friends at school like, ‘Yeah, we’re going to build a Willy Wonka Chocolate Factory.’”

If the kids were upset about uprooting their lives and moving to a Caribbean island where they didn’t know a soul, Emma doesn’t show it. Bubbly with dark hair like her father’s, she and her siblings seemed to thrive on the island, racking up awards at school and becoming junior tourism ministers. “[Bois Cotlette] was really my dad’s passion project,” Emma says. “He loves the island; he wants to share it with people. And that’s what he was doing.”

‘I’ve Been Here Longer’

Dominica, though, did not always love Jonathan Lehrer. While most everyone I spoke with only had glowing memories of Langlois and Marchand, islanders who knew the Lehrer family had decidedly mixed impressions of the Americans. Three friends from the island — connected to me via Lehrer’s publicist — claim that Lehrer is a good man who treats his employees well and would never voluntarily harm anyone. “I have never seen the monster that [the press] is trying to create in the minds of the people,” says one woman; all three friends preferred not to be identified. “He’s generous, a man who believes in value.” (Lehrer’s criminal record is also minimal, largely speeding-related.)

However, another former acquaintance of the family disagrees; he also chose not to use his name. Although he tells me that Lehrer paid better than most businesses on the island, he claims the businessman treated employees “like slaves,” declining to give them sufficient breaks for water. The man also claims that Lehrer was aggressive, mistreating his dogs and frequently carrying a gun. He sometimes even tried to shoot snakes and other pests that invaded the estate.

Lehrer’s PR denies claims that Lehrer was a strict boss and allegations of the businessman mistreating his animals. “Jonathan (and his whole family) loved their dogs — this allegation is ridiculous and simply wrong at every level,” he tells me. “Jonathan did have a gun and did indeed use it for protection against snakes and other wild animals,” he adds. “This is not uncommon at all in the area.”

The kids’ former tutor — they were homeschooled after Hurricane Maria — also seems to have had negative experiences with the family. “It was all good at first, but it became more difficult, and Jonathan became more and more controlling,” she wrote on Facebook not long after the murders. “‘No, you can’t live off the property. No, you can’t take the children to (just about anywhere off the property), etc.’ I knew I couldn’t stay, and I was heartbroken because I loved Dominica.” She declined to say more when I reached out to her on Facebook. Lehrer’s PR, for their part, alleges that the teacher was fired after “the relationship very quickly started to sour as she was overwhelmed with four kids and the impact of living in a tent.”

Some islanders — and tourists — seem to have clashed with the Lehrers over access to their property, with several folks posting on TripAdvisor that they were run off the estate by Lehrer. Lehrer, for his part, responded to each, alleging that the posters had been trespassing. Archaeologist Khadene Harris tells me she witnessed a similar streak of possessiveness when it came to the property.

“I don’t mean to be facetious, but they kind of embody a type of expat who wants to live off the grid and who kind of romanticizes being in the Caribbean and being self-sufficient,” she says. “[At first], I could tell that they seemed to have a good relationship with some of their neighbors. It was only when I went back for my long-term fieldwork that I learned that maybe relations were strained on occasion.”

She remembers, in particular, an incident where a local man passing through the estate picked an apricot from one of the trees. “Jonathan saw him with the apricot, and they had a verbal exchange over whether or not it was OK for him to pick it,” she says. “[The man’s] explanation was, ‘I’ve been here longer than you.’ And so you can imagine that people who traverse this landscape every day don’t feel like they need to ask permission to pick an apricot.” She pauses, “They’re, delicious, by the way.”

As it turns out, fruit thieves were the least of Lehrer’s problems.

‘John Is Planning His Final Days’

Lehrer tells me he wasn’t surprised when the cops arrived on that December evening. He’d heard about the murders through the grapevine, and he was one of Langlois’ closest neighbors — it was natural he’d be questioned, he says.

He was taken aback, though, when, he claims, 40 to 60 vehicles and 200 uniformed officers streamed into the estate. “The asymmetrical show of force was quite alarming,” he says. “I was scared.”

He and Victoria were in the kitchen, picking at hor d’oeuvres and airing a bottle of wine as she prepared dinner, when they arrived. “We were sitting down to eat, and the next thing I know, people are walking into our kitchen with machine guns,” Victoria tells me. They were cuffed and separated, according to the couple; Victoria was kept in a concrete jail cell for four days, where, she says, she was fed only Kool-Aid and crackers.

During that period, Lehrer says, he was under the impression that the cops were searching for illegal firearms; he claims he was asked zero questions about the murders and denied a phone call to his attorney. I ask what he was doing during the time of the crime, but he claims that since the cops never asked him that question, he has to stay mum for now. As for the local police? They didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

His lawyer, Lawrence, also declined to give me Lehrer’s alibi. “This is an active trial, and at this stage, we have only limited disclosure from the part of the state,” he said during the presser. “To date, we can confidently say that the prosecutors have no evidence against Jonathan. The items in discovery they have currently sent support Jonathan’s innocence. There has been no forensic evidence against Jonathan — nothing,” he added in a later email. As of yet, Lawrence also claims the prosecution — who did not respond to several requests for comment — has not turned over their full discovery.

Jonathan Lehrer leaves court after being denied bail in Roseau, Dominica, April 18, 2024.

Clyde Jno Baptiste/AP

Still, in court filings, police claim that “overwhelming evidence was obtained by the team of investigators,” including an eyewitness account, spent shells, a firearm, and a spent bullet and casing. They’re currently awaiting forensic testing. According to Dominica Police Assistant Superintendent Jeoffrey James, lead investigator in the case, local authorities also partnered with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to test DNA found at the scene, since Dominica does not have that capability. (The RCMP declined to comment on foreign investigations.)

While Victoria was released — she’s currently in Texas with her children — Lehrer and an employee, mechanic Robert Snyder Jr., were charged with Langlois’ and Marchand’s murders on Dec. 6. They plan to plead not guilty should the case go to trial, per Lehrer’s PR. Meanwhile, the rest of the estate’s 30 or so employees wait in limbo to see if — or when — it will officially reopen. (I reached out to several family members and friends of Snyder, who did not respond to my interview requests. His lawyer also did not respond to my inquiries.) Another employee, Norville Williams, was arrested a few days after Synder and Lehrer, but was ultimately released and, according to Lehrer’s publicist, has since left Dominica.

With both police and the prosecution largely staying silent until the trial is slated to begin in mid-September, the facts of the case are decidedly obfuscated, riddled with rumors and hearsay. Canadian outlet CTV News reported back in March that a German tourist who was in town for a yoga and freediving retreat encountered Snyder on Nov. 30, the day the Canadian couple went missing.

The man, who spoke anonymously, claims he’d wandered onto Lehrer’s property when he was shooed away by a man Lehrer’s publicist ID’d to me as Williams. The German claims that after he left the property, he heard gunshots and ran into another man he identified as Snyder. Later, he told the news outlet, “I saw black smoke [from the direction of the estates]. I heard explosions, two explosions, very loud. So for me, it was like dynamite.”

Lehrer’s PR tells me that the prosecution has not provided any contact information for the unnamed German, so the defense is unable to say much about his claims. “The tourist did say he saw both Norville and Robert as he mistakenly left the trail and entered Bois Cotlette private property — this isn’t unusual as both Norville and Robert were supposed to patrol the property for trespassers,” he adds.

Lehrer’s lawyer, Lawrence, says that Williams submitted a witness statement to the court, but claims he did not say anything incriminating about his employer. “When he came to work for us, he was on drugs. He was homeless,” Victoria tells me. “John helped him put his life together. He would have done anything for John.” She suspects he left the island because he was afraid of the police.

As for who they think killed Langlois and Marchand, Victoria and her publicist have theories galore — some more out-there than others. One involves Langlois’ now-shuttered private club, 357c, which was allegedly a favored hotspot for the mafia. “He spied on them and then turned evidence to the Mounties and the RCMP and got a lot of politicians in trouble and a lot of mafia in jail,” the publicist says. “I think one of the reasons why he left Montreal was because he might have been in fear of his life for what had transpired there.”

There is no evidence that Langlois personally spied on anyone, however, and when Quebec’s Charbonneau Commission descended on the club in 2012, commission counsel Denis Gallant said that the business itself wasn’t under investigation, per local press. “[This] is a tiny portion of the membership of this club,” he said. “In my opinion, the place is not important.… I really don’t want to focus on the club, but on the meetings.”

The PR flack also points to an incident where $1.8 million in cocaine was seized by authorities not far from Coulibri Ridge in 2018, indicating that Langlois may have been involved. “This was not out of his resort,” he allows. “I don’t know if that was a cartel situation. Again, we don’t have anything outside of what was reported by the Dominica news.” One of Victoria’s theories, however, is the wildest. “His entire background working in movies was making something look real when it isn’t…” the publicist summarizes, never really saying what’s implied: that the couple faked their deaths.

There is zero evidence, however, that Langlois was involved in anything criminal — let alone cocaine sales, mafia run-ins, or faked deaths. Lehrer’s flack perhaps unknowingly put it best when he wrote to me in one of our initial emails: “This is right out of Hollywood, with police corruption, lies, misleading the media, and even possibly faked deaths.” That’s a great tagline for a summer blockbuster, for sure, but real life isn’t Hollywood. Most of the time, the more believable answer is almost always true. Someone killed Langlois — and whether it was Lehrer or someone else on the island — they probably did so for a tragically banal reason.

Dominica: aerial view of Scotts Head, south of the island, and Soufriere Bay on the left.

Hedelin F/Andia/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

Whatever the truth is, at the moment, all anyone can do is wait for Lehrer’s day in court — which was delayed once already back in March when Snyder reportedly contracted Covid. On July 16, the legal process is scheduled to begin, and if the case is approved to go to trial, witnesses will begin taking the stand in September.

If Lehrer is found guilty, he faces death by hanging, but he claims he might not make it that long. He’s currently waiting to see if he has prostrate cancer, and alleges that the facility is denying him access to sufficient health care — a claim that prosecutors rebuffed in court documents. He was denied bail in April, partly because he still has U.S. citizenship and could be considered a flight risk.

Meanwhile, Victoria is unraveling. “John is planning his final days,” she tells me, voice cracking. “He doesn’t think he’s going to get out. I don’t know what we can do to help him. Wouldn’t it be convenient if they had nobody to prosecute? I feel like, you know, Julian Assange, his wife, probably how she feels.”

And then there’s the road case, which quietly came to a resolution this past May. Morne Rogue was declared public in a filing that describes Lehrer as “arrogant,” “defensive,” “cheeky, evasive, and morose.” The court also found that the “defendants’ behavior [has] been nothing short of a nuisance deliberately calculated to intimidate and significantly and unjustifiably interfere with the claimants and to diminish their business.”

Moreover, the ruins surrounding the estate that Lehrer was so worried about being damaged by heavy equipment? The court ruled that those don’t even belong to Lehrer, but the Commonwealth of Dominica. According to Lehrer’s PR, his lawyers plan to appeal.

“This is from the judge that crossed legal lines and made rulings about items that were never part of the case — she has had a thing against Jonathan from Day One,” the PR claims. “Then she immediately quit and left the island.… That’s a major red flag.” The court declined to confirm or deny this allegation and the judge did not respond to comment, but local news in Guyana reports that she took a new role as a judge there in late June.

That dispute seems rather beside the point now, though. Langlois and Marchand are dead, the future of Coulibri Ridge is uncertain, and there’s no telling if the Lehrer family will ever be able to return to Bois Cotlette.

‘A Man Who Had Accomplished His Vision’

As for Langlois and Marchand’s family and friends? They’re still broken — and hungry for justice. “In the beginning, I’m telling you, if Jonathan would have been released, I don’t think he would live very long,” Marchand’s friend Céline Caisse tells me.

But a few days after the murders, at least, friends and family found some measure of calm on the jetty Langlois himself helped rebuild. It was meant to be small — a peaceful vigil on the clear, blue waters of Dominica. There were supposed to be kayaks laden with local flowers, a conch-shell call, and candlelight. But the couple’s impact on the island was anything but small — and an intimate memorial wouldn’t suffice.

Soon enough, the jetty was teeming with locals dressed in purple, his favorite color, tossing flowers in the water and crying. There was barely any room to maneuver, just a wall of islanders who had come to pay their respects.

It wasn’t a perfect memorial — the sun went behind the clouds before the sunset, the circle of kayaks was more like an oblong — but Walsh still found it magical. It was imperfect, a bit wild, and jewel-toned colorful, much like his and Langlois’ adopted homeland. And the magic only spread when the locals came up to Walsh one by one to press a hand or share a hug and recall the innumerable ways Langlois and Marchand had helped them.

It reminded Walsh of another moment of levity — the couple’s last New Year’s party, in 2022. There was live music, a chocolate room that opened at midnight, champagne, and dancing. “Everything was just amazing. I had never seen Daniel like that. He was just dancing and happy,” he says. “And I said to Dominique, ‘That’s a man that’s accomplished his vision.’ And she said, ‘I have not seen him like this in years.’ He had this thing that came out of his head, and it was now real. And his friends and his people were all having the time of their lives.”