Professor Forbidden to Teach Plato Assigns Article About University Censorship Instead

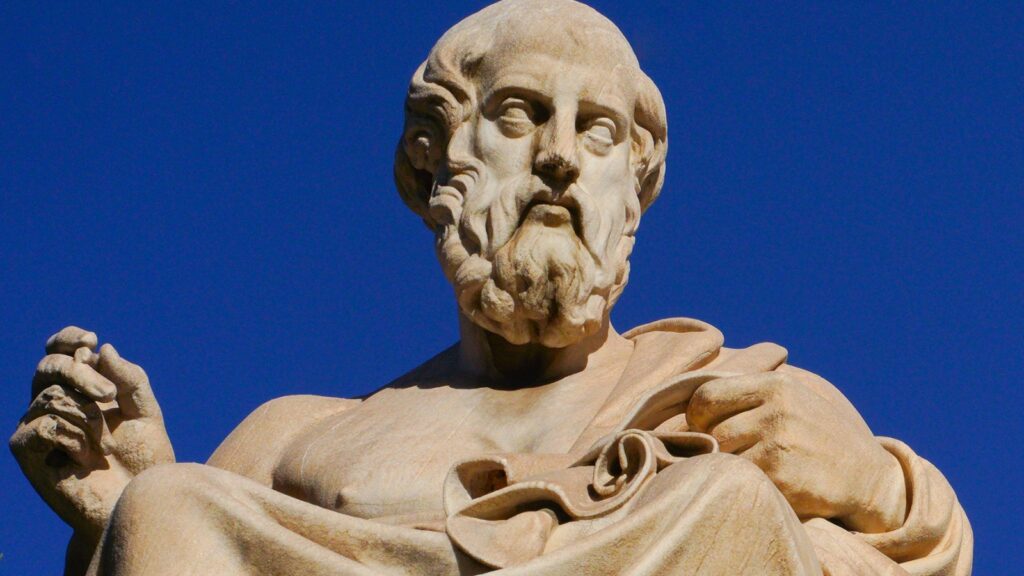

The crackdowns on “wokeness” and “liberal indoctrination” in American higher education reached a ridiculous new low last week when a philosophy professor revealed that Texas A&M University objected to him including one of history’s most revered minds on a course syllabus. The forbidden readings came from Plato, the Athenian philosopher whose work is widely regarded as an important basis for Western thought over more than two millennia.

This puzzling decision stems from an earlier controversy. Last fall, A&M fired Melissa McCoul, a lecturer in the English department, for acknowledging differences between gender identity and expression in a summer semester course on children’s literature. A student had filmed herself confronting McCoul over the material, telling her, “I’m not entirely sure this is legal to be teaching,” citing Donald Trump‘s executive order withdrawing federal recognition of transgender identity and declaring that there are only “two sexes.” McCoul eventually replied, “You are under a misconception that what I’m saying is illegal.” She then asked the student to leave.

While the class was canceled shortly after that incident, McCoul wasn’t terminated until September, when the student’s video was shared by right-wing politicians on social media to stoke outrage among their base. Texas A&M President Mark A. Welsh III then dismissed her and demoted the administrators who had not initially taken disciplinary action in the matter. Then Welsh himself, featured in another viral video where he had defended McCoul to the student, was forced out by the university’s Board of Regents, which had long regarded him as insufficiently conservative.

The institutional turmoil at this major public university was just one more example of the ripple effects of a Trump administration that has sought to restrict academic freedom. Across the U.S., many schools have muzzled professors to comply with new state laws against teaching certain topics, or as a proactive means of avoiding the wrath of the president and his allies in the culture wars. Indeed, in November — the same month that a faculty panel ruled that McCoul’s firing was “not justified” — A&M’s Board of Regents took such a step, approving new policies that prohibited instructors from broaching matters of sexual orientation, gender identity, and race or “gender ideology.”

Then, ahead of the spring semester, philosophy professor Martin Peterson, who has taught at the school since 2014, submitted the syllabus of his intro-level course “Contemporary Moral Issues” for what he called “mandatory censorship review” in an email to the head of his department. As chair of A&M’s Academic Freedom Council, Peterson noted his objections to the new policies, calling them “unconstitutional.” He also wrote that while the new rules forbade any academic course to “advocate race or gender ideology,” this core curriculum class — which he had last taught in 2024 with a nearly identical syllabus — did not “advocate” for any belief. Instead, Peterson clarified, “I teach students how to structure and evaluate arguments commonly raised in discussion of contemporary moral issues.”

The response from Peterson’s department head was curt: Drop the modules on race and gender, along with the Plato readings that touch on these areas, or be reassigned to teach a different course. He had until the end of the day to decide.

“I’ve been in meetings with deans and the provost and the president, and talked about this many times, so I knew how they are thinking about all this,” Peterson tells Rolling Stone of the new course guidelines. “I wasn’t surprised, just disappointed that the stuff about race and gender was banned. But I was genuinely surprised that I couldn’t talk about Plato, and I couldn’t ask my students to read what Plato wrote almost two and a half thousand years ago — how that could possibly be considered as too sensitive. Generations of students have read Plato.”

Peterson tells Rolling Stone that the selections of Plato’s Symposium he wanted to assign indeed deal with questions of gender identity and sexual orientation. “Sure, the content is controversial,” he says. “Plato is talking about sex and gender issues, and he is saying things that many people do not agree with. He talks about homosexuality, etc. But still, it’s Plato, one of the founding fathers of Western philosophy. The very idea that we shouldn’t be allowed to discuss Plato in the philosophy department is absurd.”

Melissa Lane, a philosophy professor at Princeton University and author of Of Rule and Office: Plato’s Ideas of the Political, echoes the idea that teaching a philosophical text is not to “advocate” for any particular perspective but to get students pondering the questions and contradictions it raises. “This is especially true in the case of Plato, given the complex nature of his dialogues, which stage debates in ways that challenge readers to think through the issues for themselves,” Lane says. “To treat Plato as advocating any particular ideology is to misunderstand the nature of his writing.”

Lane adds that the Symposium “discusses the human erotic drive as a motivating force, not only for sexual and romantic relationships but more broadly for artistic and intellectual creativity,” and “originates the idea of looking for your better half,” inspiration for countless depictions of romantic love. “To eliminate its study is to cut off a major cultural inheritance at the root,” she says. “There is a slippery slope from banning the teaching of Plato’s Symposium on a university syllabus, to banning Homer, Sappho, Rumi, many of Shakespeare’s sonnets, and more.” Moreover, Lane observes, the Symposium offers dueling narratives in its rhetorical speeches, undermining the conceit that the text pushes for ideological prescriptions. “Of all of Plato’s dialogues, the Symposium is the one that is richest in what today might be called viewpoint diversity,” she says.

In a statement shared by a university spokesperson with Rolling Stone, A&M claimed that Plato would remain on other syllabi despite their requirement that Peterson remove the philosopher from his course readings. “Texas A&M University will teach numerous dialogues by Plato in a variety of courses this semester and will continue to do so in the future,” the administration said. “In alignment with recent system policy, university administrators are reviewing all core curriculum courses to ensure they do not teach race or gender ideology.” The school said that Peterson’s materials were rejected insofar as they related to “modules on gender and race ideology,” in violation of rules approved by the Board of Regents, and that it was up to Peterson to comply or have the course reassigned.

Peterson’s predicament may be ridiculous, he says, but it’s only the tip of the iceberg: “I just had to censor a small part of my course,” he points out. “I will still be able to teach my course.” Many of his colleagues, meanwhile, “have been reassigned to teach completely different courses,” because their original courses “cannot be taught at all.” Some 200 courses at the university appear to have been affected just before the start of the spring semester — they canceled an introductory sociology class on race and ethnicity, for example, and downgraded the credit students would receive for a communications course on religion and the arts.

“I have received emails from students who support me,” Peterson says of the reactions on campus. “And I should say, I’m not one of those left-wing professors. Many students at A&M are conservative. I received an email from a former student who described himself as Christian and conservative, and who pointed out that it was very helpful to read Plato he was a student here at A&M. Even conservative Christian students agree that free speech is important and that it’s worth studying Plato.”

Rather than teach a different course, Peterson elected to revise his syllabus, replacing the Plato readings with an article in The New York Times about the university’s censorship of the original material. Administrators have approved the change, he says, and he’s looking forward to teaching it in the context of free speech and academic freedom issues. “It’s going to be very, very fun,” he says. Students who received the amended syllabus also found it annotated to highlight exactly what the school had forbidden Peterson from assigning and which alternative material had been added as a result.

Lane says that in any case, “a piecemeal ban on individual books in individual classrooms” can hardly diminish the breadth and complexity of the concepts Plato explored. “Plato has for centuries been both celebrated and attacked by both the right and the left, on a range of different issues,” she says. “His ideas have been a starting point for philosophers and political thinkers on all sides. Those who profess to care about preserving the philosophical canon in all its richness — which has been described by [British philosopher] A.H. Whitehead as ‘a series of footnotes to Plato’ — should think again.”

“It’s of course bad for our reputation,” Peterson says of the restrictions on coursework. “The idea that syllabi must be pre-approved is not something that any serious research university would be willing to do. It’s also bad for our students, right? We withhold important topics from them. Censorship is not a path to academic excellence. The university is on the wrong track.”

In Peterson’s view, A&M may have hoped to preempt future viral incidents like the one that got Melissa McCoul fired last year by keeping politically polarizing subjects out of the classroom altogether. “That was probably what they wanted to do,” he says — but now it’s backfired, and the school is once again making headlines. “I don’t think anyone is surprised that that didn’t work so well. The best way to stay out of the news and focus on research and teaching is probably let professors do what they do best, to teach the topics they find relevant and interesting in worth teaching and not try to micromanage them.”

Censorship as a method of dodging the spotlight, Peterson adds, “is not going to work well in America.” And in a few weeks, his students will have the chance to discuss why.