‘It’s All Gone’: Devastation, Survival, and Hope From the California Fires

T

he sun rose over Los Angeles County at 6:59 a.m. on Jan. 7 with many of its residents already on high alert.

In Malibu, David Hertz had spent most of the night prowling around Xanabu, his aptly named 150-acre property nestled four miles above the Pacific Coast Highway. Hertz is a quintessential Southern Californian, a thick-haired 64-year-old surfer and architect bent on building multimillion-dollar homes with recycled material. He was famous for designing and then living in Venice’s Californication House — featured in the Showtime series of the same name that starred David Duchovny — and the 747 Wing House, a residence adjacent to his current property constructed out of airplane wings. His grandfather had moved out from New York in the 1930s and owned what became known as the Hertz-Paramount Ranch in nearby Agoura Hills, where countless episodes of Gunsmoke and other Westerns had been filmed.

In the days before seat belts and helmet laws, Hertz’s father, Dr. Robert Hertz, performed facial-reconstruction surgeries at UCLA’s hospital. His dad would peel scorched visages back and then patiently reconstruct them. Hertz grew up skateboarding in Dogtown and then, in the evening, peeking at his dad’s slides of faces horribly burned and mangled. In a way, it mirrored Hertz’s experiences here in the Santa Monica Mountains, with the eternal cycle of burning, destruction, and rebuilding. All of it was etched into his personal history. One of his earliest memories is of a news report describing a forest fire that started on the Hertz-Paramount Ranch.

Despite that past, or maybe because of it, Hertz bought his current combustible property in 2017. The land had been owned by the artist Tony Duquette, who built a spectacular ersatz village called Sortilegium (Latin for “fortune-telling”) in the 1980s that featured spires and pagodas from the sets Duquette had designed for The King and I. Duquette wasn’t known for his attention to fire safety — other Duquette properties burned in San Francisco and Beverly Hills — and his landscaping made the roads to the property impassable to fire trucks. In 1993, the Green Meadow Fire quickly scorched 44,000 acres. While other nearby properties were saved, much of Duquette’s place burned to the ground.

“In its last moments, each little house and pavilion lighted up in glory and was beautiful,” Duquette said after the fire. “And then they were gone.”

Hertz began restoring the remnants of Duquette’s village that had survived Green Meadow. He built a lodge-like residence that looked up to Duquette-inspired spires. It didn’t take long for the danger to come to his front door. In 2018, the Woolsey Fire surrounded Xanabu, leaving stallions at an adjacent ranch shrieking in terror. Power and communication failed. Hertz and his caretakers held off the flames as the fire licked the edge of his property. Eventually, some surfer friends arrived and tamped down embers and watered down Xanabu. Still, Hertz fled the land, driving his truck through fire after three days of fighting the flames. Exhausted, he called his wife.

“It’s all gone.”

Architect and volunteer firefighter David Hertz, 64, is lifelong Los Angeles resident.

Laura Doss

But it wasn’t. The wind changed, and Xanabu was spared. Hertz vowed to do better. He installed an elaborate sprinkler system and made the property water self-sufficient with a creation called SkySource that grabbed moisture out of the air and stored it in giant tanks on the property. (The invention won him an XPrize for innovation.) He put a repeater on top of a nearby mountain to improve radio communication in case cellular service was knocked out.

Hertz and friends professionalized their own fire-defense abilities, forming eight fire brigades that trained and worked with the L.A. County Fire Department. They were never intended to be frontline fighters, concentrating more on evacuation and mopping up fires that were already mostly out. One benefit was that they could bring what they learned to protect their own homes.

Still, Hertz knew it might not be enough. Climate change had already moved in, causing schizophrenic changes in the weather. Los Angeles experienced wet winters in 2022 and 2023 that left brush the height of corn stalks before harvest. A biblical drought came in 2024, and now the brush kindled waiting for a spark.

On the night of Jan. 6, the U.S. Forest Service issued extreme red-flag warnings, indicating “imminent danger.” Hertz walked through Xanabu in the dark, checking his sprinklers, his fire equipment, and his truck. The sun came up, and Hertz, in his yellow fire jacket and boots, listened to his radio. He knew the fire was coming — he just didn’t know from where.

So he waited.

IN ALTADENA, 77-YEAR-OLD John Joyce greeted the high-wind warning with excitement. He woke up around 8 a.m., put on his glasses, and ran his hands through his steel-wool-gray hair. Finally, Joyce reasoned, he could begin to repay the debt he owed Jeff Ricks, the owner of two Altadena houses and a series of adjacent cottages Joyce managed in exchange for a place that he had called home since 1998.

Managed is not exactly the right word since Joyce also served as muse/wise uncle to the 28 artists who lived in the two main houses (known as 2656 and 466), cottages, and converted garages forming what the residents like to call John Joyce University, a name he hated because he believes in collective progress, not individuality.

The residences were happy places, with a playhouse for kids on the porch. The front yard was often filled with stretched canvases of the paintings they were working on. Inside, art was everywhere, from abstract works to giant papier-mâché puppet heads. There were Bernie Sanders signs and a giant Thelonious Monk poster. You might wander into the living room and find Joyce sawing at his work table, while a performance artist slowly danced with a CPR dummy as the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby” played in the background.

Much of Joyce’s life had been tumultuous, marked by fleeing the Bay Area in the late 1960s after he was arrested by the FBI for not reporting to his draft board.

He wandered the country, battling depression, until he landed in Altadena in the 1990s. Unincorporated and wild, the town on the edge of L.A. suited him.

John Joyce, who manages property in Altadena, has lived there for 27 years.

Courtesy of John Joyce

Two decades ago, Joyce had fallen in love with Susie Stroll, a photographer and professor. But they were at different stages of life: She had free time and wanted to travel; he still had to work and was happy in his artist community. They broke up. In 2022, Stroll found Joyce’s address and wrote him a letter. She said turning her back on him 16 years ago had been her biggest regret.

They began seeing each other again in January 2024. Almost immediately, Stroll started having problems with her balance and speaking. In November, she was diagnosed with ALS and was moved into an assisted-living facility in nearby Pasadena. Stroll’s throat constricted, which made eating solid foods impossible. Joyce had a solution. Every day, he would buy a pumpkin pie and then ride his Triumph motorcycle to see her. There he’d mash the pie and feed her tiny fragments.

Her condition worsened, and she was transferred into hospice, just a few blocks from Joyce’s home. She died on Nov. 24. Still grieving, Joyce felt guilty about the chores and projects he had ignored on Ricks’ properties. The high-wind warning gave him a chance to catch up. There were things to tie down, and Ricks’ extensive automobile collection, including two Mercedes and a classic Ford Galaxy, had to be repositioned far from bending trees and other debris.

UNINCORPORATED AND WILD, THE TOWN ON THE EDGE OF L.A. SUITED HIM.

“I can be the hero,” thought Joyce.

Joyce got himself a cup of coffee in the shared kitchen. A writer was grumbling that Donald Trump’s imminent return to office had left him unmotivated. Joyce suggested he look at it a different way.

“The Marxists say all you have to do to destroy capitalism is let it naturally do itself in,” said Joyce. “Let history just go and it will turn into total fraud, and it’ll turn into a monopoly. It will self-destruct. We can do the same with Trump.”

Joyce and his friend agreed the world could use a little destruction.

He went outside to start on his chores. The whipping debris drove him back inside. He put on a bike helmet for protection. A few minutes later, he returned and switched to his motorcycle helmet. He flipped the visor down and began moving the cars.

A BLOCK AWAY, Joyce’s best friend, Molly Tierney, a photographer, cleaned up her home and left food out for her cat, Wallace, named after the California artist Wallace Berman. Tierney was from Minnesota, where she played on a hockey team before moving to Altadena and a spot in the 2656 home. Friends joked that she still lived her life like she had a stick in her hand. Joyce knew the artist to be a young, wise soul, and after four years, he urged her to check out an abandoned house about 50 yards away.

Tierney decided to squat on the property, a decision Joyce supported. She lived in a makeshift shack for the first five months without running water. Slowly, she began clearing six tons of debris out of the century-old home and quietly paid back taxes on the property. From mail deliveries, she realized the property was owned by a trust run by a man who died without an heir. Tierney consulted a lawyer who told her to stay on the property but make no waves for at least five years. She went further and waited a decade. Tierney scored legal possession of the home during the pandemic. It still didn’t feel quite real.

Artist Molly Tierney has lived in Altadena for 19 years.

Courtesy of Molly Tierney

The artist had not slept much the past two nights. The Santa Ana winds kept her awake. Overcaffeinated, she was stressed, but Joyce calmed her, telling her that windstorms and fire threats were part of life, but would never reach them, a good mile below the Altadena foothills.

Reassured, Tierney cleaned up her home and brought in some outside furniture. There was a friend to pick up at LAX airport that night, and her day job working for the artist Paul McCarthy was busy in a good way. The friend was an admirer of her art, and they had been corresponding for months. She jumped into her Ford Focus, clearing some falling brush from the windshield, and headed to the McCarthy studio in nearby Lincoln Heights. Her friend’s plane was due to arrive at 8 p.m. She didn’t want to be late.

A MILE WEST, Donald Kincey got ready for his job, teaching second-graders at the Chandler School in nearby Pasadena, where the kids called him Mr. Donny. Kincey also ran the school’s after-care program, so his days could stretch 10 hours. His friends marveled at the 46-year-old’s endless energy and patience.

“Kids get me,” Kincey told them with a smile. “I just talk to them like little human beings, and it works.”

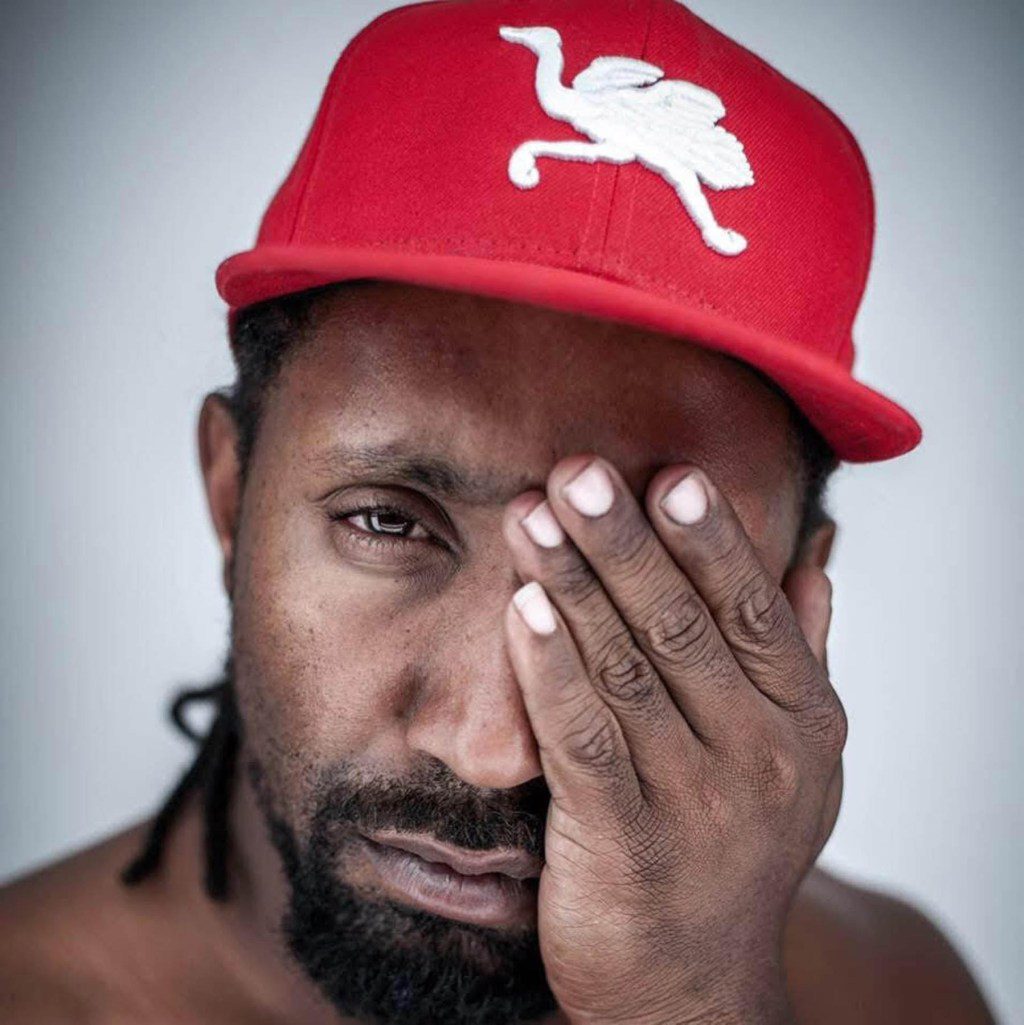

Forty-six-year-old teacher Donald Kinsey has lived in Altadena his whole life.

Courtesy of Donald Kincey

Kincey was born and raised in Altadena. For nearly a century, the town had served as a haven for African Americans while many other towns still had sundown laws and operated under the bullwhip of Jim Crow. Kincey’s family traced their California roots to his grandparents fleeing Oklahoma after the 1921 Tulsa race massacre. They found a home here, with jobs as mechanics and postal workers. Not that it was perfect; both Kincey’s father and grandfather reported being followed home by county sheriff’s officers throughout their lives.

Kincey was both in and out of the community as a kid. Attending public schools, he was careful not to wear baseball caps that might be mistaken for gang symbols, but he could ride his bike all over town. It was the urban-rural mix of Altadena that he loved the most. He shot baskets at nearby Farnsworth Park, watched the creative types planting flowers in abandoned bathtubs, and then cruised by the liquor store where cowboys from the neighborhood’s horse farms would tie up their horses while they bought a six-pack. Kincey swam and played soccer in the supposedly more-affluent Pasadena, but Altadena was his home. He went to Morehouse College to study, and loved the vibrant Black culture of Atlanta, but something kept calling him back.

I HAD RELUCTANTLY left Los Angeles for Vancouver in September after two years in Santa Monica, where my boy could play basketball outside every day of the year. My family had preceded me, and before I left, I made the drive up to the Reel Inn, a Malibu fish shack I’d hit maybe a hundred times over the past two decades.

It had been about 100 days since my last meal at the Reel Inn. Since then, I had crisscrossed the country covering the presidential campaign. I watched Trump get elected and then traveled to London and Stockholm. On New Year’s Eve, in Iceland, I snapped a photo of my son in front of a massive Reykjavik bonfire. He beamed in front of the flames.

Los Angeles received just a trace of rain in all that time.

IT’S EASY to shorthand Los Angeles as a dream factory, a place populated solely by movie stars, award shows, influencers, and surfers. It has become so prevalent that writers declaring “The Death of the California Dream” has become its own ecosystem. (I have a folder on an old laptop, collecting the best of the genre.)

What is forgotten is that there are 10 million people trying to live that dream. And it might not be the dream you suspect. An Armenian couple scraping together money for a bungalow in Glendale. A mom raising a son alone in Westwood after the suicide of his father. An East L.A. family afraid of ICE moving in the shadows near MacArthur Park. These are not the type of dreams optioned by producers like Scott Rudin, but they are dreams all the same.

The people I talked to after January’s wildfires had dreams. In 24 hours, they ignited, flashed, and then vanished into the toxic darkness.

New dreams can be conjured, but first the nightmares have to fade.

IT WAS AROUND 4 P.M. WHEN EVERYTHING WENT TO HELL.

AROUND 10:30 A.M., Hertz heard on his police scanner that smoke had been spotted in the Pacific Palisades, a nearby Los Angeles neighborhood.

The Palisades looked down on the Pacific Ocean from posh homes, a few that Hertz had designed. The smoke was quickly replaced by fire, and it spread rapidly, metastasizing from five to 50 acres in minutes. Hertz called his men, and they agreed to meet at Zuma Beach, about a 25-minute drive from Xanabu. They were not firefighters in the traditional sense — they had no big engines, just individual pickup trucks tricked out with hoses and water tanks. Eventually, the brigade commanders decided to send Hertz and his three-man crew 12 miles south to Duke’s restaurant, which firefighters were using as a staging area. They were then told to cruise through the nearby Las Flores and Big Rock neighborhoods above the Pacific Coast Highway and spread the news that the Palisades Fire was growing with frightening speed.

They found a surreal scene. Their radio crackled with news that the fire was heading their way like a caged beast unleashed, but they saw retirees riding bikes and moms pushing kids in strollers. The consensus was that the fire was still 10 miles away; they’d wait and see what happened.

It was around 4 p.m. when everything went to hell. There was a black swirl of smoke as Hertz hit the PCH, reducing visibility to near zero. Hertz had to tailgate the vehicle in front of him the three miles to the beach. They pulled into the Topanga Beach parking lot. That’s when they spotted a vast pyro cumulus cloud spinning down the cliffs behind the Getty Villa. Private firefighters and staff protected the museum, but the fire tornado devoured everything else. Hertz and his firefighters started banging on the door of an RV parked on the PCH. The confused driver cracked the door. Hertz screamed at him.

“You’ve got to move!”

Above, a Sikorsky helicopter tried to make a water drop on the raging flames, but it was no use. Winds whipped at more than 60 mph, and the fire tornado, estimated to be between 50 and 100 feet wide, started shifting toward the Reel Inn, across the street from Topanga. Hertz and his men moved behind the restaurant, trying to wet the ground and tearing down a fence that would just provide more fuel to the fire. A few moments later, one of the Reel Inn’s windows blew out and the checkerboard tablecloths ignited. There were no hydrants nearby, so the brigade was left pumping out water from their meager supply. Hertz felt his face flush as the heat moved toward them. He spotted the fire advancing toward a propane tank and ordered his crew to retreat. They jumped into their truck and headed to a parking lot a quarter-mile away from the fire and, crucially, on the other side of the PCH. From there, they watched the Reel Inn explode and disintegrate. It had all taken less than 30 minutes.

The radio barked out that the fire was now sweeping through the Palisades. The brigade dispatch reported that the flames were threatening the home of one of its members, Tyler Hauptman. Hertz consulted with his men and made a decision: They would try and save all of the houses on Hauptman’s block. He pointed the truck through the flames, and down the PCH.

Volunteer firefighter Hertz battles the Pacific Palisades fire.

Clay Bush/Impulsephoto

He took a left onto Temescal Canyon Road and headed up the labyrinth of streets that makes the area hard to navigate for newcomers. It wasn’t quite sunset, but the sky was black, interrupted only by a blizzard of white, thousands of burning embers being swept through the streets. Hauptman’s house sat at the top of a ridge, a sharp undeveloped drop nearby, with the village and Palisades Charter High in front of it. By the time the brigade arrived, the school was ablaze and reports came in that flames were devouring an area called the Alphabet Streets.

They climbed to the roofs in Hauptman’s neighborhood and looked out at a world that was ceasing to exist. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power had not turned off the power, and electric poles burst and shot sparks into the night. A member of the crew swore and stated what was now obvious. “Fuck. Holy fuck. This has gotta be the worst fire in L.A. history.”

The brigade went to work. They hooked up their hoses to a hydrant and set up mobile pumps to draw water out of swimming pools. Only a few minutes later, Hertz had a horrifying realization: The fire was now moving up the hill behind the home. There was no fire department presence except for a lone emergency vehicle.

“Can you help?” asked Hertz.

But the petrified driver was just looking for a way out of the Palisades. This seemed prudent. By 6 p.m., an hour after their arrival, Hertz and his small crew were surrounded on all sides by flames.

“Hey, over there.”

A car was on fire. They put it out.

“Behind the house!”

A crew member moved in and beat the flames back.

Around 6:30 p.m., the men heard what sounded like a machine gun firing up the street. It was a neighbor’s ammo stash catching fire.

Water pressure was dropping, but it didn’t really matter. “All the water pressure in the world can’t save this,” said Hertz, pulling off his mask to wipe a dark line of sweat.

At that point, all of the houses except Hauptman’s and a few nearby homes were on fire, multimillion-dollar properties crackling like twigs in a summer campfire.

Around 7:30 p.m., Hertz realized the wind, smoke, and flames had left him disoriented. For a minute, he didn’t know exactly where he was. It was a horrifying and frightening feeling. He wondered if he’d have to pull out his fire shelter, a supposedly flame-resistant pup tent that firefighters climb into when a fire overruns them. He reoriented himself and told his men that it was time to get the hell out. His truck was low on fuel, and water pressure was anemic. Besides, the wind had shifted. Miraculously, Hauptman’s house was out of danger. The men packed up and drove back down to the PCH. He dropped off his men at Duke’s and arrived home after 1 a.m. His hair and face were filthy with dirt and smoke. He gave his worried wife a hug.

“We saved Tyler’s house,” Hertz told her. “I guess that’s something.”

He then passed out on the couch.

But he was wrong. The winds changed again. The Palisades ran out of water. He woke up at dawn. That’s when he learned Tyler Hauptman’s house had burned to the ground.

“FUCK. HOLY FUCK. THIS HAS GOTTA BE THE WORST FIRE IN L.A. HISTORY.”

MOLLY TIERNEY HEADED back to Altadena from the McCarthy studio in nearby Lincoln Heights in the early afternoon on the day of the fire. She was worried; news of the Palisades blaze was everywhere, and the wind was whipping up in a way she had never seen before in her neighborhood.

She texted John Joyce, who fought the wind as he made the five-minute walk to her house. He urged her to head to LAX. Reluctantly, Tierney agreed and got in her car. She didn’t get far — a text from a friend told her a fire had been reported in Eaton Canyon, four miles from her place. She drove home and loaded up her car, just in case, with the deed to her house, her passport, and all of the hard drives holding her photographs. At the last second, she headed back in for a beautiful pail with a naked woman on the side that was a paintbrush holder her grandmother had made for her grandfather.

It was now 7 p.m., and she left for the airport. Usually, Tierney wouldn’t mind being a little late, but tonight it was different: She had never met the man before. Two hours later, they hugged in the arrivals terminal at LAX. Then Tierney told her new friend something important.

“I’m not sure I have a house anymore.”

AROUND THE SAME TIME, Donald Kincey arrived at his sister’s place on Poppyfield Drive, a little more than a mile west of Tierney’s house. His family owned several homes in the neighborhood, and he was currently living in his sister’s house while she worked as a doctor in Bakersfield. He’d heard about the Palisades Fire and the high-wind warnings, but he was ready to ride out the situation. The simple two-level house with a black iron fence lining a small yard was close to open forest, but the neighborhood had survived before — there had been only one previous evacuation order. “I’m 11 blocks from the mountains,” Kincey told worried friends. “The whole neighborhood would have to burn up before my house got hit.”

Kincey spent the next few hours shuttling between his sister’s and his parents’ home on Alta Pine Drive, a five-minute drive away. (His parents spent several days a week in Bakersfield helping take care of his niece.) He brought in furniture and secured doors and windows. By midnight, he was exhausted. He texted his sister that everything was OK but she would have to buy some new shingles.

Kincey watered the yard and driveway outside his sister’s home. He then took a shower and got ready for bed. The fire still seemed distant, and he had to be at school in eight hours. But something made him set an alarm that would go off every 15 minutes. He woke up around 1:30, and the night glow had changed to a more-intense bright red.

It’s still coming, thought Kincey.

For a moment, Kincey considered getting some of his artwork out of the garage behind the house. He’d been working on a giant acrylic work of Kobe Bryant being swarmed by Boston Celtics defenders. But then there was a crackle that sounded like gunfire. A palm tree above the house had caught an ember. It burned quickly, shooting out flames that looked like tracer fire. A nearby house caught fire. Kincey picked up a garden hose and started wetting his sister’s property again. The torrent of water quickly became a trickle and then nothing. He ran into the house and turned on a faucet. It was dry. Altadena had run out of water. Now was the time to get his art. He headed down a narrow path on the side of the house and toward his garage studio. The wind knocked him down, and the heat stopped him after a few steps. It was too late.

Kincey jumped into his truck. He headed to his parents’ house and grabbed some of his father’s artwork. Suddenly, he felt a burning feeling: His hair had been scorched by an ember chunk. He put it out, got into his truck, and raced out of Altadena toward Pasadena. He didn’t stop until he hit the Rose Bowl parking lot, where he parked his truck next to other refugees. A few hours later, the sun tried to rise through a haze of fire and smoke. That’s when Kincey learned that both his sister’s and his parents’ homes were gone. More and more reports filtered in: Friends and relatives had lost their homes too.

And that’s when Kincey realized his whole life — his history, his past, his future — no longer existed.

MULTIMILLION-DOLLAR PROPERTIES CRACKLED LIKE TWIGS IN A SUMMER CAMPFIRE.

JOYCE DIDN’T LIE to Tierney. He thought everything was going to be fine. But he didn’t know all of the facts. The Eaton Canyon Fire started at 6:15 p.m., when sparks were seen in the hills about three miles from Joyce’s location. A resident tried to put out the small flame and then watched it spread exponentially. In just minutes, embers were spotted a mile away from the initial spark. At 7:15 p.m., an attack helicopter with thousands of gallons of water was turned back by winds now gusting well over 80 mph.

Embers could now be seen on Santa Anita Avenue. The town was lit by an apocalyptic orange tinted by the red lights of fire engines mobilizing throughout the hills. Around 8 p.m., Chris Pack, a resident responsible for a gorgeous vegetable garden on the 2656 property, started banging on the cottages and converted garages, telling the occupants it was time to go. Susannah Mills, a painter and end-of-life doula, had left her place an hour earlier and taken her cat to her boyfriend’s house in Silver Lake. She then returned to 2656 to grab some belongings and keepsakes. The wind nearly ripped the door off her car. She fled back down Santa Anita Avenue dodging downed trees and residents fleeing on foot. Terrified, she spied an old man trudging slowly away from the fire, a suitcase rolling behind him.

As Jan. 7 became the 8th, Joyce shuttled between the two houses. He wanted to save it all — his friend Jeff Ricks’ properties, but more important, the community where he had spent the happiest days of his life. The 2656 house had a loft tower with giant glass windows that blew out in the early morning hours. Quixotically, the 77-year-old returned to his workshop at the other house, cut a giant piece of plywood, and struggled to carry it the 400 feet from 466 to 2656 in winds now gusting over 80 mph. Breathing through a respirator, Joyce sweated and groaned as he lugged the plywood up the stairs. He quickly realized the wind was too fierce; there was no way he could nail it over the opening.

Then, he got an idea. There was a thick old fire hose in the loft that Joyce had installed for Ricks. Its purpose was not to put out flames, but to provide a device that his buddy could rappel down — superhero style — in case of a house fire. Joyce returned the hose to its designed purpose. He hooked it up to the sink and ran it out the window. It worked. He began watering the grounds and returning back to 2656 where he did the same with some garden hoses.

Joyce ran between the properties for another two hours. Then, in the Bible-black predawn, he climbed back up into the loft and looked out at the fire on the hill. Something was different. The fire was now moving like a prowling carnivore, feinting down one street a few blocks away and then changing its mind and slithering down a different avenue. A friend who was monitoring an L.A. fire app called him. She told him houses were ablaze just a few streets away. Joyce looked down at the gravel in the driveway. It was simultaneously blackening and smoldering.

Everything he loved was burning away. He called Ricks and told him that it didn’t look good. Ricks reminded him of a favorite anecdote. Years ago, Ricks, a relentless consumer and eccentric investor, had bought the entire contents of a Vegas porn shop thinking it might have vintage material worth something. For years, Molly Tierney had busted Ricks’ balls about the investment, telling him that among all of his worldly goods his collection of worthless porn was clearly his dearest possession. Joyce always laughed and egged her on. Now, as the world melted, Ricks told him to get the hell out of there.

“It’s all replaceable, except for my porn.”

Joyce laughed through his respirator. He gave himself two minutes to pack up his truck. He grabbed a white shirt and a tie for Susie’s funeral the following week. But in the darkness, he grabbed the wrong box — he didn’t have his tie.

The truck was nearly loaded when he saw it: a river of embers flowing down Santa Anita Avenue right toward him. A house up the avenue exploded. He looked up, and the palm trees above 466 were spinning with flames, fiery pinwheels spitting sparks at him. He closed the truck’s door, did a U-turn, and sped away.

Three blocks down the road, he slammed on the brakes. Joyce had forgotten something: his teeth. He turned around and charged back up the hill. But in the two or three minutes since his initial departure, the fiery holocaust had somehow become even more deadly. Cars everywhere were ablaze, and a dome of embers arced above the avenue like festival lights strung above streets in Little Italy. For the first time, Joyce was filled with fear and dread: He was lost on a street he had lived on for nearly three decades. He thought for a moment that this is how it ends. But then the wind blew the flames clear. He could see smoke shooting out of Ricks’ loft. Reoriented, Joyce realized he was going the wrong way.

Forgetting about the teeth, he dodged flaming wreckage for a half mile until he hit Woodberry Avenue. There, he saw the terminally-ill patients at the hospice where he visited Susie just a few weeks ago being evacuated. A pile of abandoned stretchers and wheelchairs lined the ground. Joyce pointed his truck south, uncertain where to go. Eventually, he jumped on CA 210 East and drove until the smoke cleared. He then pulled over, tore off his respirator and gulped in the first breaths of fresh air since the fire had started 12 hours earlier.

For a moment, Joyce thought he had failed. He had not been able to protect Ricks’ homes or the countless pieces of art created by his friends. He had told Tierney everything was going to be fine, and that turned out to be untrue. But then he had a moment of clarity. Everything was gone, but as far as he could tell, everyone he loved was still alive.

And that was something.

DONALD KINCEY’S PASTOR was persistent. She wanted him to speak to her flock at Sunday services, five days after the fire. Kincey is a quiet and thoughtful man, not prone to self-promotion, and at first told her no. But then at the service, an 88-year-old woman named Fay spoke to the congregation. She had lost everything, but one thing remained: her faith in God. After that, Kincey felt obligated to say something.

He spoke of the rich history of artists and athletes in the Altadena Black community. There were no tears until he began talking about himself and his family. His mother’s roots were deep in Altadena, but his father had been raised in Compton in the time of the Black Panthers and the Civil Rights Movement. Kincey said he had always wished he had more of that kind of courage for himself. Now he did.

“My pride died in the fire, so did my fear,” he said through tears. “Now, anything that comes my way, I’m going to say, ‘Why not?’”

John Joyce had lived on this street since 1998, managing a group of cottages.

John Joyce

I FIRST DROVE UP to 2656 with Chris Pack, the house’s constant gardener. Jeff Ricks’ cars were mostly melted metal, with an old roadster looking like its own art project, jagged melted plastic resembling lightning bolts hung to the trunk. Pack’s cottage was nothing but ashes. He openly wept until he noticed something in the pile. They were intact pieces of his grandmother’s nativity scene: the shepherds, Mary, and the baby Jesus. Later on, we came across a haggard old man. He wore a hazmat suit but had only a surgical mask protecting his lungs. He was furiously digging up piles of debris at what used to be the home’s front door. It was John Joyce.

“I can’t talk now,” shouted Joyce with a gasp. He was looking for a fire-resistant box that held the home’s deed and rent payments of some of the residents. “I have to find it — it has the deed, everything.”

I returned the next day with Susannah Mills, the artist whose car doors were nearly torn from their hinges at the height of the fire’s rage. She had a better mask and other gear for Joyce. He wasn’t on the property, so she sifted through her own belongings; art books seemingly intact floated away in a cloud of ash when opened. We drove with her boyfriend a few blocks to the Altadena Community Church where she worked. The church had been a haven for the displaced and forgotten in L.A., whether they be transgender or immigrants. But there wasn’t much left. A sign reading “Sanctuary” hung on a surviving pillar, but now pointed to nowhere. The office where she worked no longer existed. A chain-link fence remained with a gate holding a sign that read, “Please don’t slam the gate. Close gently.” Mills picked it up. “I put that sign up there. It doesn’t need to be there anymore.” I could hear her sobbing through her mask.

I circled back to the properties and caught a startling sight. At the front of the 2656 house, Molly Tierney stood and tried to get Joyce’s attention. He was still digging for something. Tierney shouted his name.

“John!”

Joyce finally pivoted. Tierney promptly dropped her pants and mooned him. Joyce stopped digging for a second and stood perfectly still. Then, he mooned her back.

And the guy Tierney picked up at the airport? Tierney gave me a shy, devilish smile and said, “He has been such a comfort.”

Molly Tierney squatted on this property for a decade before it was officially hers.

Courtesy of Molly Tierney

I spent hours over the next two weeks talking to Joyce, first over coffee as wind still whipped through Altadena, raising fears of further terror, and then on a series of FaceTime calls once I returned home. He sent me a stream of photos of his finds, some great — Ricks’ lockbox was intact — and some grisly: the burned skull of a friend’s cat.

I realized our talks were a salve for him, replacing his morning coffees with his artists who had scattered for shelter. He told me of his life before Altadena. He told me tales of boxing in an off-the-book match in New Jersey and tending bar at the White Horse Tavern in Manhattan. There were adventures, but also mental health struggles and loneliness that lasted until he moved to L.A. in middle age. The artists at 466 and 2656 had given him a home where he could talk about surrealism and play an exquisite corpse. He wasn’t seen as a drifter weirdo, but embraced as a friend and a brother. He smiled as he remembered the conversation with the writer the morning of the fire.

“I guess I caught more of that Marxist destruction than I thought,” joked Joyce. Eventually, we talked about why he worked so hard to save the homes.

“It was all hubris,” said Joyce. He paused for a long time.

“I think the places gave me so much love and happiness I just didn’t want to see it all go away. But everything goes away, people go away, art goes away.” He pointed out toward a couple of his friends going through the ash, looking for a talisman that helped propel them forward. “But I still have them, and they still have me.”

There’s talk of rebuilding their community and fiercely defending their Altadena. (The surviving boba-tea shop and halal market down the road already had “Don’t Sell Out Altadena” signs to warn off real-estate investors.)

Some priorities have changed. For years, Joyce had dreamed of taking his Triumph out on the highway to visit friends in Las Vegas and New Mexico before they died or he got too infirm for the ride. But the Triumph was now just another pile of twisted metal. He had a new bike in mind. He showed me a photograph of a different motorcycle, one his gearhead friends were prepping for him. “It’s a real off-road bike. It can tow things and ride over logs and stumps. It’s got a real Steve McQueen thing going on.”

He smiled.

“It’s going to be great for rebuilding. I’m on a new journey now.”

THE TOWN WAS LIT BY AN APOCALYPTIC ORANGE TINTED BY THE RED LIGHTS OF FIRE ENGINES.

I SPENT TWO DAYS with David Hertz. First, we retraced his day in the fire in his brigade truck. We drove up the PCH in Malibu and tried to maintain our bearings with so many hotels, houses, and bars gone away. Always the architect, Hertz talked about Malibu’s future as he drove us through checkpoints.

He pointed at the burned remnants of houses on the ocean side. “How do you rebuild there? The beach behind it was completely worn away. Where are you going to put a septic tank?” He pointed down to the horizon toward a faraway beach. “That’s Point Dume. Unless you owned one of these homes, you could never see it from here before.”

At my request, we pulled into the Reel Inn parking lot. All that remained was black wood and the restaurant’s neon sign. For years, the sign’s lights had told me it was time to slow down and find a parking space. Now, it was dark. I took some photos of the charred remains of one of my favorite places in the world, while Hertz thought back on the flames. There had been harsh criticisms of L.A.’s response to the fires. The mayor was out of the country. A Palisades reservoir was empty due to delayed repairs. It would not have mattered, according to Hertz.

“This is where I knew this wasn’t like any other fire,” he said. “It just moved so fast. You could have had 5,000 firemen and endless water and you could not have stopped it.”

We drove into the Palisades, and Hertz showed me the lots where houses that he built no longer existed. Burned-out cars with X’s on them, meaning cadaver-sniffing dogs had checked them. He looked for the house of his son’s girlfriend. We had to circle the block twice, slowly creeping by at a crawl. It simply wasn’t there anymore. He called his son.

“Yeah, it’s all gone. I’ll try and get you up here soon for a look, but there’s nothing here.”

The following Saturday, the skies above Malibu were gray as I turned right off the PCH and ended up toward Xanabu. Hertz opened the gate and greeted me warmly, clad in Blundstones and black wind-resistant gear. He showed me around the property and all of its enchantments: the pagodas, the house made of the 747, and the gazebo with the views all the way to Santa Barbara.

In the end, the Palisades Fire didn’t reach Xanabu, ironically meeting a natural end when it hit the burn of the Franklin Fire — there was no more fuel to feed it.

“The Indigenous tribes did natural burns for centuries,” said Hertz. “It’s not the answer to everything climate change is causing, but it can help.”

We walked around for a bit, pausing to stare out at the endless vistas and the beautifully garish huts. Still, I could not help but think Xanabu was a fire trap despite Hertz installing sprinklers, capturing his own water, widening roads, and personally honing his own fire skills. Eventually, I worked up to asking the impolitic question: What the hell was he thinking driving into the mouth of the fire in a Ford truck with three part-time firefighters?

“Look, that wasn’t the plan,” said Hertz. “But that was the situation. People helped me when I was in danger, and I wanted to repay that.” He chuckled softly. “But, yeah, I do look back on it, and there are some things I learned. Keep an eye on your exit route.”

Regarding preserving Xanabu, he used one word repeatedly.

“It’s the definition of folly,” said Hertz. “I know it’s folly and one day it could all be gone, but I love it and I’m going to cherish it. If it’s not here, there will be other beautiful things in our lives.” He then repeated something he often tells his wife: “When you die, they don’t bury you with a U-Haul. Enjoy it all while you’re here.”

Hertz had to run; he was late for a ceremony honoring the brave work of the Malibu fire brigades. I shook his hand and then went for a drive. I stopped at El Matador Beach and thought of the waves I’d negotiated for years and the magic-hour beers consumed with a Navy-pilot buddy. I continued south and pulled into Point Dume, where my son put his feet in the sand for the first time. I made a trip up to Agoura Hills and pulled into the driveway of the old Paramount Ranch. It was all gone. I’d forgotten that Hertz told me it had burned to the ground during the Woolsey Fire.

I doubled back down the PCH, then I showed my credentials at a checkpoint and was allowed to stop in again at the Reel Inn. I looked out at the ocean and realized Hertz was right — views were now even more spectacular. And I thought the architect was right about something else: It was all folly. The restaurants. The beach shacks slipping into the sea. My memories.

But it was a beautiful folly. A few hours later, a light rain began to fall over Los Angeles.