How ‘World of Warcraft’ Reinvented the Global Gaming Community

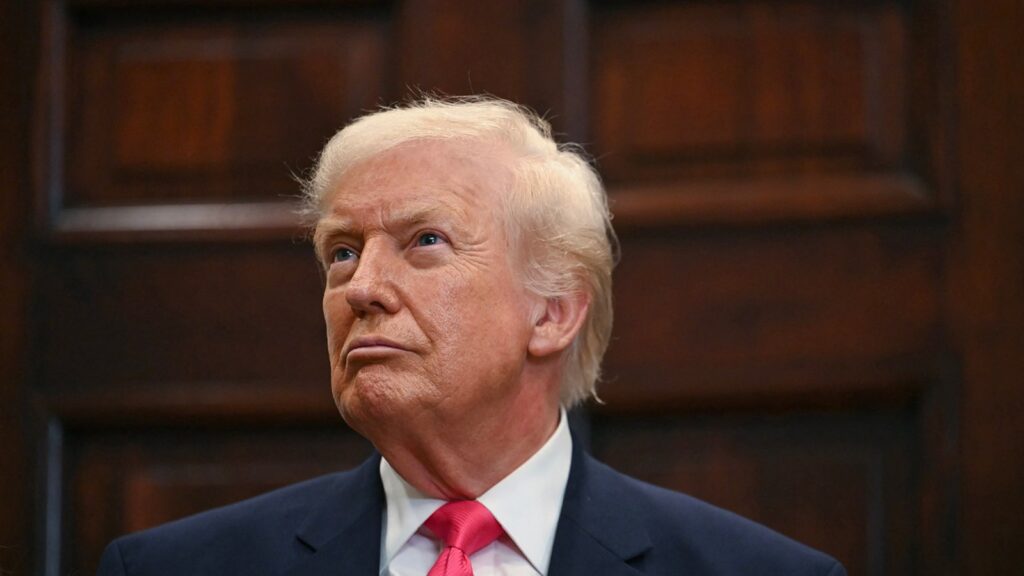

In an age when more and more games have taken on the continual live-service model, only so many can gain traction (some only last a few days). Given how many falter, it’s a badge of honor that the OG, 2004’s World of Warcraft, has survived so long that it’s nearly old enough to drink. Two decades is a long time — multiple generations in the gaming industry — and though World of Warcraft has had its share of ups and downs, the fact it is still going strong after 20 years is a testament to the world developer Blizzard created back in 2004 and has continued to expand upon ever since.

At its peak in the mid-to-late 2000s, World of Warcraft was a cultural phenomenon in a way few games have ever been or ever will be. It revolutionized the niche genre of “massively multiplayer online role-playing games” (MMORPGs or MMOs, for short) and made the then-burgeoning world of always-online, large-scale community gaming appealing to the masses.

It adorned the labels on cans of Mountain Dew. There were Toyota Tacoma ads that positioned the truck as a trusty steed for serious adventurers. Celebrities like Mr. T, Chuck Norris, Aubrey Plaza, William Shatner, and even the prince of darkness himself, Ozzy Osbourne, all appeared in commercials advertising the MMO. And, of course, nobody can forget the infamous “Make Love, Not Warcraft” episode of South Park, 22-minutes of comedy gold that helped propel Blizzard’s world into the mainstream consciousness.

A world, however, is nothing without people to inhabit it. Hundreds of millions of players have called Azeroth, the titular “World” of Warcraft, home over the years, all paying $15 a month for the privilege. There is a reason Blizzard’s recent Warcraft 30th Anniversary Direct, where it announced what’s next for the MMORPG, took the time to put a spotlight on the relationships both fans and Blizzard employees gained through playing the game. Much of the game’s enduring and ongoing legacy is the social bonds players have forged in its virtual world. Some say they’ve met many of their closest friends, or even their significant others, while adventuring in Blizzard’s fantasy world.

World of Warcraft as a social space where friends can meet, relationships can bloom, and guilds of dozens (or hundreds) of players can create lasting communities has been one of the game’s few constants over the years. Blizzard’s MMO sparked an online social revolution before the age of social media, one where players could find common ground in a world they would go on to call a home away from home. For World of Warcraft’s 20th anniversary, Rolling Stone spoke with Blizzard and members of the game’s community to learn why players keep coming back to a two decade-old game, the lifelong memories they’ve made because of it, and how it’s the community that keeps the world of Azeroth alive.

More Than A Game

Stories of lifelong friendships and Blizzard’s game bringing players together aren’t uncommon, World of Warcraft‘s executive producer Holly Longdale tells Rolling Stone. Longdale says Blizzard hears about the impact Azeroth has had on people’s lives all the time. One of those stories, the life of Mats Steen, is the subject of the recently released Netflix documentary, The Remarkable Life of Ibelin. Steen suffered from Duchenne’s disease, a form of muscular dystrophy that gets progressively worse over time. As his condition worsened, he found comfort in World of Warcraft, where he forged friendships as an active member of a roleplaying guild. Though he died in 2014, Blizzard’s game let Steen live the life he couldn’t in the real world, and much of the film is animated using World of Warcraft‘s in-game models and assets to recreate Steen’s digital life.

Blizzard had almost no involvement in the film’s creation, aside from giving the film’s creators its blessing to use their intellectual property to tell Steen’s powerful story. But Longdale says stories like Steen’s reminds the developers responsible for World of Warcraft that “sometimes a game is more than a game.”

For many players, World of Warcraft was more than a game. It was a lifestyle.

Blizzard Entertainment

“You remember those things every day,” Longdale says. “When you sit down at your desk, it gives you some perspective on where our focus should be… The team takes it very seriously.”

She had her own personal stories to share, too. Prior to working at Blizzard, Longdale worked on what was, at the time when World of Warcraft first launched, the game’s primary competition — Everquest. She recalled the first moment when playing World of Warcraft that she knew Blizzard had created was something special.

In the early days of Azeroth, those who made a night elf character would find themselves on the opposite end of the world from the rest of their faction, the humans, dwarves, and gnomes of the Alliance. Once outside the night elf starting zones, players needed to hop on a boat, sail to another continent, and then make a long run through dangerous territory in order to make it to the dwarven capital of Ironforge and continue their adventure. It’s a rite of passage millions of players have embarked on at some point in their World of Warcraft careers.

Every player starts in their own race’s region, then discovers the larger world at their will.

Blizzard Entertainment

“Along the way, I was running and somebody had some run speed [buffs] I didn’t have next to me and his character buffed me,” Longdale says. “I think it was the Hunter buff, Aspect of the Cheetah. We started talking and he just added me to a group without even asking. ‘Let’s do this, let’s group up and run to Ironforge together.’ And I still talk to him to this day. That is just the magic of an MMO.”

Clan Battlehammer

That “MMO magic,” those random, player-to-player interactions inside a digital fantasy world that have the potential to blossom into lifelong friendships, is what keeps many players coming back to World of Warcraft all these years later, even as Blizzard has over time sanded off many of the game’s rough edges that once served to organically push players together.

One longtime player, who asked to go by their in-game name, Pragus, remembers fondly the personal connection World of Warcraft fostered in the early days. “The original WoW was a beautiful sandbox; It was a server and you knew people,” Pragus says. “It’s grown, but they’ve grown away from that.”

Clans and guilds are ways to people to play together, but it becomes a true commitment.

Blizzard Entertainment

Pragus is the current co-leader of Clan Battlehammer, an all-dwarf roleplaying guild on the game’s Emerald Dream server that focuses on open-world player-versus-player encounters. The guild has existed since 2009, when a player named King Bruenor grew tired of the endgame loot grind Blizzard intended. He was frustrated by players who would join a guild, participate in an endgame raid to get some of the game’s best epic-quality gear, and then bail once they had what they wanted, leaving their fellow guildmates out to dry. Instead, Bruenor sought to build a long-term community within Azeroth that was there for more than just color-coded lines of code.

Though Bruenor stepped away from the guild in 2022 for personal reasons, eventually leading to Pragus helping lead the current iteration of Clan Battlehammer, Pragus says the culture and traditions Bruenor instilled still exist today.

“It’s been around for 15 years,” Pragus says. “I’m not saying it’s been 40 dwarves strong all 15 years. When “xpacs” [expansions] come around and we recruit, boom, it’s 40, but there are times when we will be down to like five dwarves… But those five people are there keeping the lights on and then people come back and it’s the same names.”

Massive dungeon and boss battle raids require tight coordination, and emphasize the teamwork.

Blizzard Entertainment

One member, who requested not to be named, has been in the guild since 2010 and is now over 70-years-old, says they consider members of the guild their close friends. Were it not for the guild, he says, he would have stopped playing World of Warcraft long ago. Instead, the camaraderie he’s found within Clan Battlehammer will keep him playing “until I can no longer use a computer.” Pragus says much the same — if not for Clan Battlehammer and its community, he probably wouldn’t still be logging on day after day, year after year.

“People can come together across state lines, country lines, and make something special around something they love, in our case, dwarves,” Pragus says.

Clan Battlehammer was built for spontaneous open-world PvP (players vs. players) battles, an activity that has become progressively more challenging in recent years. Originally, players would pick a World of Warcraft server for their character based on what kind of experience they wanted from the game, whether that was roleplaying, PvP, or PvE (players vs. enemies). Each server existed as its own micro-community within the greater World of Warcraft ecosystem.

“Dead” Server

Back in 2004, server capacity was nowhere near where it is today, and only a few thousand players would call a particular server home. Due to the relatively small size of servers and the need to group with other players to complete dungeons, raids, or challenging quests, players would bump into the same people time and time again, further strengthening the bonds and relationships between players. The same went for players on the opposing faction. Over time, players got to know the famous, and infamous, names and guilds on each server, giving each micro-community its own identity and flavor.

World of Warcraft took the concept of a LAN party and made it global over the internet.

Ricardo DeAratanha/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Now, servers are many times larger. Rather than having to manually group for dungeons or raids, players can simply click a button to be matchmade with a group of players from across different servers. More recent server technology used by Blizzard, like “sharding,” — which weaves players from various servers together based on the needs of the game while out in the open world, largely to help improve server performance and make it so thousands of players aren’t all in the exact same spot — has further made server specific communities less relevant. The kind of organic interactions where players bump into each other out in the open-world, whether they be friend or foe, and forge an ongoing social relationship, are now more infrequent.

“I and a lot of people, a lot of old-schoolers, do miss the days of back when we had enemies that we knew who they were, they had names,” Pragus says.

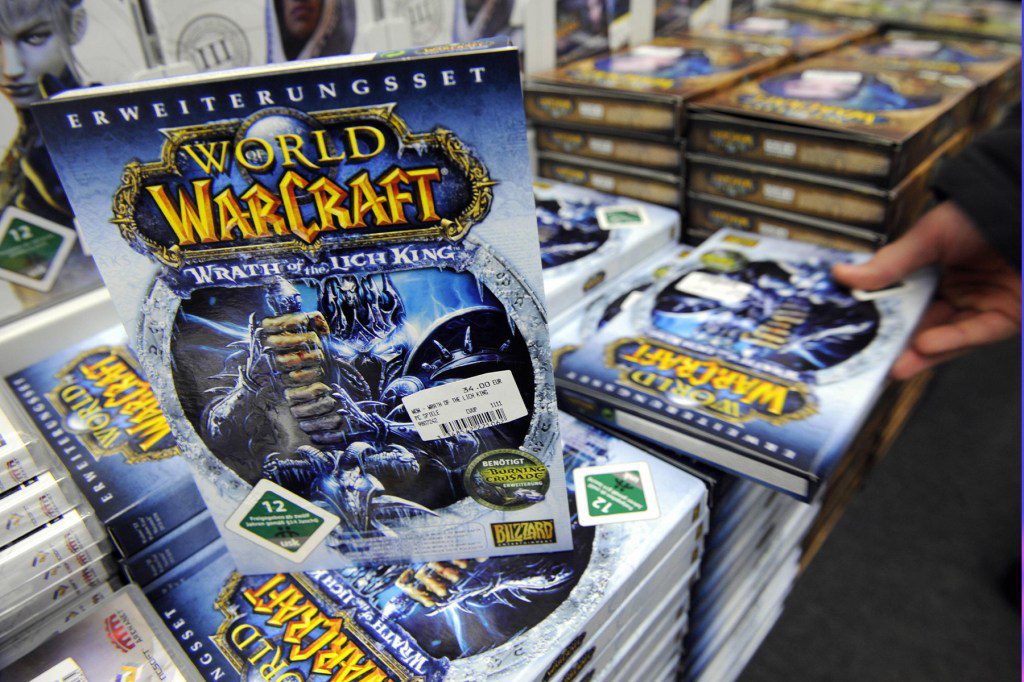

For those looking for a more “old-school” experience, Blizzard officially launched “Classic” servers for World of Warcraft in 2019. These recreate the game as it was in its early years and first few expansions, separate from the more modern, “retail” version of the game. In Classic, there is no “sharding,” no matchmaking for dungeons (at least, for most versions), and servers are still their own communities, albeit ones much larger than they were when World of Warcraft originally launched.

Specific servers have different functions and require support from the community and developers.

Blizzard Entertainment

World of Warcraft Classic‘s Arcanite Reaper server in 2020 was an exception. At the time, the server was infamous for its low player population, so much so that there were community organized “re-roll” campaigns on Reddit to inspire new players to join the server and restore it to a “healthy” state. Those efforts helped for a time, but many players weren’t in it for the long haul.

Shortly after the launch of a “Classic” version of the game’s first expansion, The Burning Crusade, players on Arcanite Reaper began leaving in droves, paying Blizzard to transfer their characters to other, more populous servers where it would be easier to find groups and make progress.

Suddenly, there were barely even enough max-level players on Arcanite Reaper to make up a full endgame raid team. The auction house, where players could sell and buy items amongst themselves, was basically useless, as there were simply too few items and too little gold in the in-game economy.

It wasn’t long before there was only one endgame guild on the server — the appropriately named Rock Bottom. For its members, persevering on what many described as a “dead” server, and the bonds that were forged because of it, became part of the game’s appeal.

“Classic” mode was introduced in 2019, allowing players to relive the game as it was in the 2000s.

Blizzard Entertainment

“A lot of it was philosophical opposition to Blizzard basically extorting us,” Zach, one of the guild officers in Rock Bottom says. “‘You’re not going to get to have a good experience unless you pay us $25 to move your characters to a new server.’ If we’re gonna move, you’re gonna let us do it for free Blizzard. We pay you $15 a month to play this game, we’re not going to give you extra money because our server sucks. It’s your job to make our server good.”

And so Rock Bottom persisted. Against all odds, the guild, barely able to scrape together a raid team and serving as its own auction house, battled through the early phases of The Burning Crusade’s endgame content on a server that was, for all intents and purposes, their own personal world. The guild’s struggles brought the ragtag group closer together, and soon many were declaring they were “Rock Bottom for life.” Along the way, the guild leader, whose real name is Dusty, was trying to draw attention to Rock Bottom’s plight on social media.

“I was actually tweeting at the developers, Holly Longdale and a few others, for a while,” he says. “I was very passionate about saying ‘Hey, we’re from Arcanite Reaper, we are down to 30 or 40 people. We are the only raiding guild on this server. We pay a monthly subscription. Our ask is that you give us a gameplay experience where we can actually enjoy this game as a MMORPG and not the fiesta we had to endure.’”

World of Warcraft didn’t invent expansions but it made them cultural events, foreshadowing gaming’s future.

THOMAS LOHNES/DDP/AFP via Getty Images

Eventually, Blizzard listened. Players on Arcanite Reaper were granted free server transfers. Rock Bottom found a new home, recruited new members, and, for a time, blossomed. Rock Bottom finished out The Burning Crusade and eventually progressed to the next Classic expansion, Wrath of the Lich King. Two members who joined the guild during that time fell in love, got married, and now have a child. Though Rock Bottom would eventually disband, many of the core players who had come together during the guild’s Arcanite Reaper days are still friends today and have continued to play World of Warcraft together.

“Looking back on it, it was one of those really cool experiences you could only have in WoW,” Dusty says. “I wouldn’t trade the memories, the highs and lows, for much.”

World of Warcraft has changed dramatically over the years. One need not look any further than the fact that players can currently pick between five different versions of the game. But no matter what version is being played, World of Warcraft has always been, and will likely always be, a social experience — not only because of Blizzard’s intentional design decisions, but sometimes in spite of them.

When asked why she thought World of Warcraft was still around after 20 years, and what makes the game special, Longdale didn’t hesitate: “It’s the community.”