‘Life is Strange: Double Exposure’ Is a Cozy Gaming Take on ‘Twin Peaks’

While art doesn’t always require an audience, Square Enix’s choice-driven adventure game Life is Strange quickly found a home among young gamers (especially in the queer community) with an affinity for indie music and quirky sci-fi adventures thematically akin to Twin Peaks. Inspirations aside, Life is Strange has found longevity of its own, and since 2015 has blossomed beyond the scope of its initial cast of colorful, preppy characters with successful sequels highlighting America’s cultural diaspora.

Like auteur David Lynch did with his own follow-up, 2017’s Twin Peaks: The Return, developer Deck Nine made the curious choice of dipping once more into the creative well of the past with its upcoming release of Life Is Strange: Double Exposure (out Oct. 29). It’s a game that controversially sees the return of the series’ original protagonist, Maxine Caulfield, nine years after players already determined her fate.

Since its official announcement at the Xbox Games Showcase in June, Double Exposure has fought an uphill battle to justify its existence to longtime fans. On the one hand, fans are excited to see their blorbo evolve from the awkward high school photographer with time-rewinding powers to a college-aged adult. On the other hand, others are concerned that her surprise return will see Deck Nine fumble the impact of the bittersweet multiple endings from the first game, dragging Max out for yet another traumatic adventure.

Having played the first two episodes of the game (released on Oct. 15), I can say Double Exposure not only justifies its creative decision to bring Max back but also sets the stage for a rich, emotionally resonant game that might dethrone True Colors (2021) as the best entry in the series.

A Familiar Setup

Upon first blush, Double Exposure sets itself up as the video game equivalent of Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015) in how its setup feels like a familiar copy-paste of the first game — albeit with some prominent distinctions. Like in the original, Double Exposure sees Max set up a new life for herself, this time at the prestigious art college, Caledon University. Gone are the days of Victoria Chase and her gaggle of Mean Girls telling Max to “go fuck her selfie.”

Now, Max is a teacher’s assistant who has to contend with the school’s demonology-inspired frat group, Abraxas. Fortunately, she doesn’t have to navigate her new academic life alone because she’s got her new bestie and the principal’s daughter, Safi, to help her through tough times. That is, until Safi’s found murdered on campus grounds.

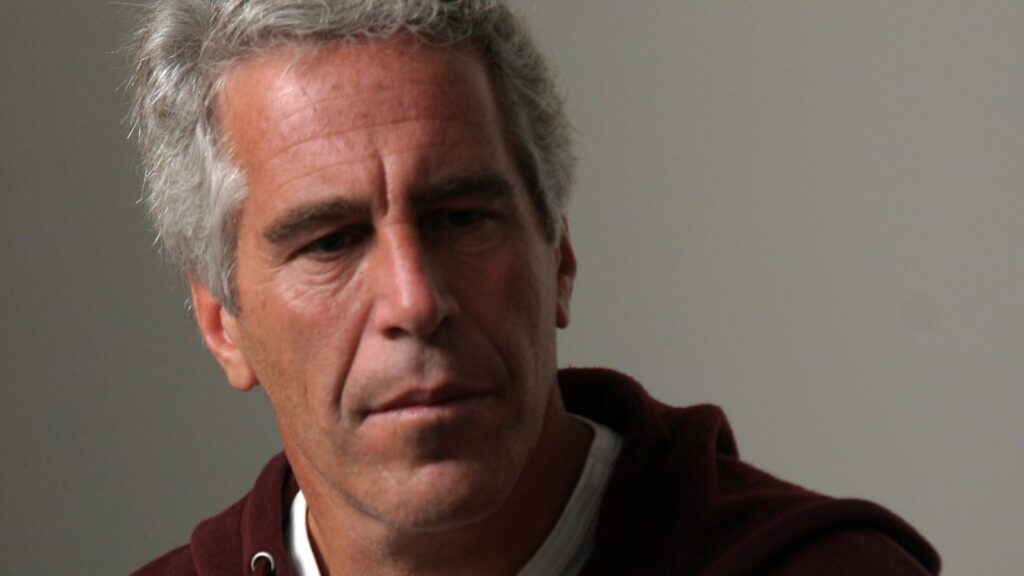

Bringing back Max as the lead following past trauma was controversial but intriguing.

Square Enix

This narrative ripple echoes a similar misfortune that befell Max in the first game, wherein she rewinds time to prevent her childhood best friend, Chloe Price, from dying and is tasked with solving an overarching murder case not dissimilar to Twin Peak’s Laura Palmer. Double Exposure maintains the series’ penchant for boldly wearing its inspirations on its sleeve. Although Double Exposure rhymes with the distinct vibe of Life is Strange, it doesn’t settle for resting on its laurels as an exact copy of its originator with a new coat of paint. Double Exposure puts in the work to justify revisiting its main protagonist in how it explores the series’ prevailing theme of loss and rehabilitation on three fronts: the past, the present, and a what-if future.

One of the reasons Life is Strange is so beloved in the gaming community is its inherent representation of the queer community, key to which is the romantic pairing of Max and Chloe. This choice was rare at a time of predominantly heterosexual relationships in gaming that, more often than not, didn’t give players the option to opt in. Players are also given the opportunity to save a queer character who is otherwise doomed by the game’s narrative to die.

Changing the Exposure

Whereas the first game saw Max overcome situational and psychological horrors by rewinding time to solve environmental puzzles and unearth clues about the game’s ensuing murder mystery, Double Exposure sees Max without her time-altering powers, and for good reason.

Double Exposure wastes no time addressing fans’ fears over canonizing either of the first game’s endings, where Max is forced to choose between saving Chloe and sacrificing her hometown of Arcadia Bay. Most players who shipped the two chose the former, which the series seems to have unofficially canonized through its post-game comic book runs.

Players can canonize either of the original game’s endings in dialogue.

Square Enix

However, the devs insist on neither ending being canon and respect players’ choices by giving them the opportunity to follow through with whatever ending they choose through an innocuously placed catch-up conversation between Safi and Max. While this decision isn’t unique to sequel games, Double Exposure goes the extra mile by having the player’s endgame decision persist as a third storyline that teases the deeper reason for why Max endeavors to trudge forward with her newfound parallel time hopping powers.

Pricefield shippers discover that Max and Chloe get the chance to live happily ever after for a time before ultimately Chloe breaks it off with her. Naturally, their break up leads Max to sequester herself and compartmentalize her lingering feelings for Chloe. Spoilers aside, Double Exposure weaves a narrative of how their breakup impacts Max’s inability to use her rewind powers in the game.

This narrative decision creates a third story thread in tandem with Max’s time-hopping one, where she looks back on her past relationship with Chloe through old text messages, diary entries, and lurking on her social media posts. It also cleverly serves as an anchoring point for both Max and the players to explore the issues with obsessing over loss by reliving the past and the desire to break free from one’s trauma to live for the future.

Leaving her time travel powers behind, Max can now bounce between two realities.

Square Enix

Max’s double exposure timeline powers double both as a fresh gameplay mechanic and as a narrative throughline for the series to supplant Max’s past indecisiveness through her do-over time powers with increased stakes where all branching dialogue choices are permanent and will ripple throughout the game — regardless of the timeline.

Like its predecessors, Double Exposure is a showcase for how video games can push the envelope with strong choice-based narratives and inventive mechanics. While Max no longer has her time rewind powers, she has manifested a newfound ability to rift through binary timelines where Safi is alive and dead. Deck Nine has players cleverly navigate Max to fixed points in an environment symbolized sonically and visually through a tinny ringing sound and an aberration of blue and orange bokeh lights. This new power set not only encourages players to scrutinize every nook and cranny of the game for clues, it also forces them (and Max) to confidently trudge forward and commit to their decisions instead of harping on the past.

A Double Dip

Double Exposure isn’t without its faults. While the narrative so far has been strong, it does have some niggling issues with its visuals. On occasion, graphical hiccups in the game’s clay-like 3D character models and environments lead to delayed texture pop-ins and people snapping abruptly into place in scripted cutscenes. While not entirely immersion-breaking, they are certainly distracting, given much of the game is crystal clear when it’s working properly.

The game is pretty at times but has some technical issues, as well as some consumer practice issues.

Square Enix

Unfortunately, while Double Exposure’s is a story fans want to pore through, it’s marred by Deck Nine’s downright predatory monetization of its release, which promises players early access to the game’s first two episodes two weeks before its official release if they purchase the $80 Ultimate Edition. The base game is $50, and while the extra $30 premium adds some small cosmetics and new content, it’s almost entirely a shortcut preying on the eagerness of fans to return to this world just a bit sooner.

A crucial part of Life Is Strange‘s success model is as a community-driven game that everyone can play episodically, and commiserate or engage in discussions online as the pieces fall into place. Together, folks can make fan theories and build their mutual excitement for the next episode. With this new release model, the developers and publisher Square Enix have monetized the community aspect, while still dumping all the episodes out on the official release day. The previously organic group experience is now pay-walled for a two week exclusivity window.

Lately, gamers have become complacent, like toad in the boiling pot, when it comes to gaming’s monetization practices — be they with microtransactions, loot boxes, and exorbitantly priced editions of games with the promise of early access. While being nickel and dimed by game companies has become commonplace for consumers, Square Enix’s stunt with Double Exposure and the ensuing fan outrage over its release proves that some people are fed up.

The Ultimate Edition adds cosmetics and some extra content, but mostly abuses fan’s love for the series.

Square Enix

For players who can’t or won’t fork up the extra cash, the only alternative is to avoid all online spoilers. Regardless of the game’s quality, the deliberately profit-minded release model cheapens the spirit of the series, and is a practice that feels wholly antithetical to Life is Strange’s ethos.

Overall, Double Exposure honors players’ personal experience with its progenitor by making your past decisions reverberate in Max’s. It’s a game about unpacking the throes of loss, piece by piece, and fighting for a better future. Longtime fans of the series will be on the edge of their seat to witness how their branching decisions from the game’s past and present unfold when Double Exposure releases on Oct. 29 for PlayStation 5, Xbox Series X/S, Nintendo Switch, and PC.