Sebastian Maniscalco Sold Out MSG Five Nights in a Row. He’s Still Deciding What Success Means

L

ast Friday, comedian Sebastian Maniscalco had Madison Square Garden roaring with laughter with bits about Amazon deliveries scaring him when they arrive at midnight, the total oddness of New York City’s so-called rat czar, the voracious moles devouring his yard, and his wife’s (allegedly) bad driving. He pulled faces, changed his flat Chicagoland patter into silly voices, and contorted his body into knots to bowl over the sold-out crowd. At the end of the night, he warmed everyone’s hearts by inviting his mom and dad, both immigrants from Italy, onstage to share in his pride. Even though the couple divorced a little over 15 years ago, they looked visibly proud of their 51-year-old son.

When Maniscalco left the arena for a light Italian dinner (he acknowledges he’s mildly allergic to pasta but, hey, he eats it anyway since it’s “worth the pain”) he felt victorious. He’d won over the 18,000 people who showed up for the third show of his five-night run at MSG — a record for the most consecutive comedy shows at the venue — on his It Ain’t Right tour. The next day, though, he learned only 17,999 audience members had completely lost themselves in the moment.

It’s Saturday morning, and Maniscalco, seated in an austere conference room at Manhattan’s Four Seasons Hotel, is dressed in a powder-blue tracksuit. He’s more relaxed than his onstage persona, speaking more slowly and in a deeper voice. Looking at his phone, he chuckles as reads aloud a text his mom, Rose, sent him: “I had such a great night, loved every moment.” He glances up with a “so far, so good” smirk, then reads on: “You looked hot up there. It seemed like you lost your way, but then you got back on this set.” He chuckles.

“There’s no ‘You had a great set,’” he says, more amused than annoyed. “There’s always something that [my parents] noticed that was a little off and they got to mention that. This is the beauty of having parents like this, because there’s no way you get a big head in this business.”

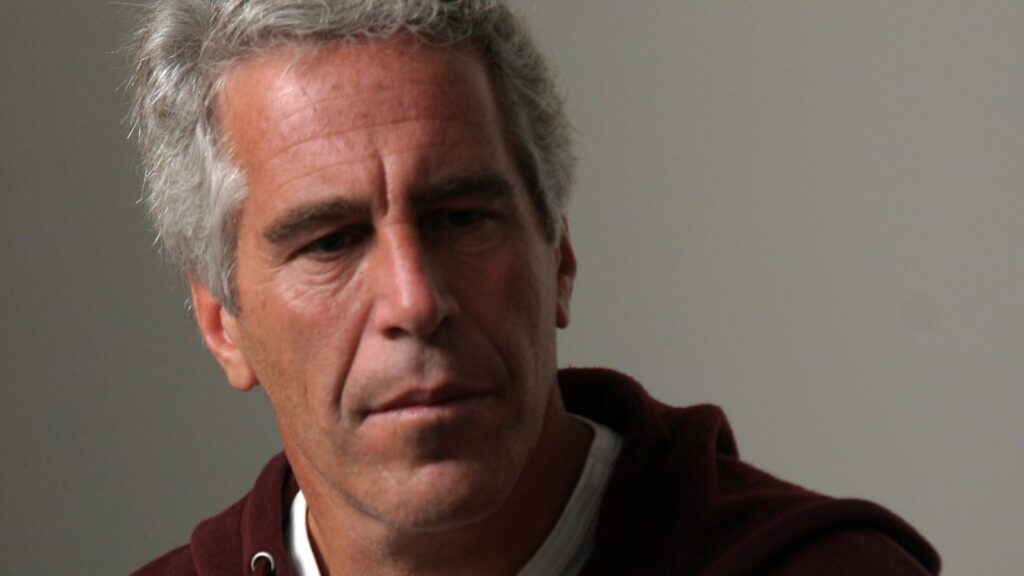

The expressive, physical side of Maniscalco’s comedy borrows a little from Jackie Gleason.

Peter Fisher for Rolling Stone

If anyone could have a big head at this point in his comedy career, though, it’s Maniscalco. Over the past couple of decades, he rose out of the L.A. club scene to become one of the most recognizable working stand-up comics today. He shared screen time with Robert De Niro in the 2023 movie, About My Father, which he co-wrote, and stars in an HBO series, Bookie. Now, he’s on the road, performing dozens of dates from coast to coast. The tour may well be his last for a while, since he’s more interested in film and TV these days than spending two years generating 75 minutes of material about his family.

Maniscalco’s folks should be no strangers to anyone who’s followed his comedy. They’ve inspired some of his best material over the years, while also encouraging him behind the scenes. His dad, Salvatore, a hairdresser, helped subsidize the comedian’s move in 1998 from his native Chicago to Los Angeles, where he waited tables at — wait for it — the Four Seasons and begged for stand-up slots at the Comedy Store. More recently, Salvatore begrudgingly rearranged his work schedule so De Niro could study him in order to portray him in About My Father. The elder Maniscalco was not too starstruck to complain about the inconvenience. “He’s like, ‘I got clients. I can’t take three days off,’” Maniscalco says of his dad. More than 25 years into his career, his parents still make for some of his best material, along with his wife, Lana, and their two kids, ages five and seven.

Early in Maniscalco’s MSG set, he joked about how kids today go to sleep-away camp, but he didn’t get that experience back in the Eighties. “In the summer, my father put me in the backyard,” he joked. “For three months: ‘Go in the backyard.’ So I just ran all over. ‘Oh, it’s windy over here.’ I was bored my whole childhood.

“You don’t tell your parents in the Eighties that you’re bored,” he continued. “I tried that once: ‘I’m bored.’ [His dad:] ‘Go dig a hole! Go look for worms!’” The way Maniscalco hollered and lunged during the bit had the audience in stitches.

In his 2018 memoir, Stay Hungry, Maniscalco wrote that his father raised him with the mindset that “the Maniscalcos never win,” meaning nothing in life comes easy to the family. It’s taken close to three decades, but now, the comedian has achieved everything he could have hoped for as a stand-up. His record MSG stint bested even iconic comedians like Chris Rock and Dave Chappelle.

Over the years, Maniscalco has developed a unique stage persona that feels like a potent mashup of comedy influences — a little Seinfeldian observational humor, the everyday befuddlement of Kevin James, the sandpapery bristle of Andrew “Dice” Clay, the blue-collar, cross-eyed apoplexy of Jackie Gleason — and parlayed it into movie and TV roles.

“I know I’m having a lot of fun when I’m carefree,” Maniscalco says.

Peter Fisher for Rolling Stone

The only thing really off limits in his act is politics. “You see politics on your iPhone,” he says. “You see it when you go home and pop on the TV. You see it on the computer. Politics is constantly in your face.” I tell him that somebody shouted out “Trump” in my section during his show and he just says, “Oh, really?” Then he clarifies: “Regardless of who you like — if you like Trump or Harris — I feel like people want to just leave that at the door and enjoy a night of comedy, and then you could pick it back up the next day. I’ve always felt that whatever my father or my family is doing is a lot funnier than whatever the political candidate at the time is doing.”

BY ALL ACCOUNTS, Maniscalco’s life right now is good. It’s been ages since he waited on Four Seasons patrons; the five-star hotel’s waiters now serve him drinks (and he still doesn’t appreciate his fellow guests’ sense of entitlement). But with the spoils of hard work surrounding him, when he’s asked how he defines success, he sputters.

“Nobody has ever asked me that,” he says. He’s hesitant to define a sense of personal accomplishment by tickets sold or money earned, though he acknowledges that if he were to enter the Garden and there were only 12 people in the audience, he’d consider that unsuccessful. After thinking the question through out loud, he decides, “Success for me is just being happy.”

When has he been unhappy? “Have you ever had sciatica?” he asks, referring to a condition that sends excruciating nerve pain shooting down your leg. “It’s cruel. It hits you like a lightning bolt.” A couple of years ago, those bolts would strike him mid-set and cripple his timing. He couldn’t play with his kids. Even lying down hurt. He tried Lagree method Pilates, an endurance test of its own, and it helped treat the pain, which cleared up two and a half months ago — just in time to get It Ain’t Right right.

On Friday night, he told a joke about having to give a urine sample at a doctor’s office, lurching forward to the left and right as he mimicked peeing like a crouching animal. “There’s no way I could have done that joke that way two years ago,” he says between sips of tea. “When I was doing that joke, I was thinking, ‘Well, it doesn’t hurt.’”

When he’s really into his act, though, he doesn’t think much at all. He improvised a joke that night about what a bad driver his wife is and by morning, he’d completely forgotten he even made it. (“The way she drives is awful, just terrible,” he nevertheless maintains on Saturday.) “Those are the moments I love the most onstage, when you’re in the pocket,” he says. “I know I’m having a lot of fun when I am just so carefree.”

Success by more concrete metrics he recognizes only in hindsight. “I didn’t even know there was records to be broken,” he says of his MSG milestone, leaning back in his chair. “It’s something that I’ll probably look back on later and shake my head at and go, ‘Wow, we really did accomplish something great.’ We’re just doing five shows in the city, and we’re going to go next week and do Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.” Similarly, he’s only just now making sense of the fact that he made a movie with De Niro, an actor he’s looked up to practically since birth. (A high point for him was De Niro coaching him how to cry on-camera, which involved thinking of his father’s struggles as an immigrant.)

So, for the moment, Maniscalco is just trying to enjoy the ride. He’s doing 94 performances over eight months, by his count. When he’s offstage, he keeps life simple. It’s hard being a dad on the road, so he tries to make time to take his kids out; they hit the Oculus, a mall in lower Manhattan, while in New York. When the kids are not around, he golfs, plays basketball with the other comics on the tour, and visits attractions in the cities he’s playing.

Maniscalco says his parents, immigrants from Italy, keep him from having “a big head.”

Peter Fisher for Rolling Stone

Last week, he ascended the Empire State Building to look out at the city. “I was looking at the Statue of Liberty and then playing this out in my head, going, ‘Wow. My dad’s 80. Sixty-five years ago, the Maniscalcos immigrated from Sicily by boat and they came through Ellis Island,’” he says. “And 65 years later, I’m doing these five shows in New York City. I’m so grateful that my parents are here, are alive to see this.”

He looks at a photo of his parents taken at the previous night’s show. His father is looking off to the side, taking in the crowd; his mother is smiling ear-to-ear at the camera. “You could just see my mom is so over-the-moon happy,” he says.

So with all this validation, what does it mean now to Maniscalco to “stay hungry” — since that was his mantra less than a decade ago when he wrote his book? “I’m full,” he deadpans. “I think I’ve adjusted my perspective. I’m still hungry, but I know when to eat and when not to.”