The World Is Falling Apart. Broadway’s ‘Suffs’ Urges Us to Keep Marching

In “Find a Way,” a number at the beginning of act one of the Tony-nominated musical Suffs, Alice Paul (played by Suffs composer/lyricist Shaina Taub), mulls over the logistics of planning the 1913 Women’s Suffrage Procession, the first major activist march on Washington, D.C. “How will we do it when it’s never been done? How will we find a way when there isn’t one?” she muses.

Within the world of the show, it’s a legitimate question: Paul has little organizing experience, and as the show documents, she must endure overwhelming obstacles, such as force-feeding and torture in prison, before women finally win the right to vote, seven years after the march. But it’s also a fair question for the Suffs audience, who at the time of this writing face the similarly daunting obstacle of being six months away from an election that may very well hurtle us, ass-backward, into fascism. How can we do what’s never been done? How can we find a way, when, as the election of 2016 and a subsequent pandemic, insurrection, and overturning of fundamental reproductive rights have made clear, there really doesn’t seem to be one?

When I speak to Taub in her dressing room a few days prior to the release of the original Broadway cast album of Suffs, she says she doesn’t see the lyrics as a reminder of our dismal current climate, marked by infighting and bullying at best, and outright apathy at worst. She sees them as an exhortation. “I’m not bullshitting you,” she says. “I look forward to doing the show every night because on my worst days, to put the news app down and go on stage and sing ‘How will we find a way?’ to feel an audience get fired up in moments of protest — it lifts me back up.”

Taub, 35, is something of an optimistic pragmatist. She is not quite as much of a firebrand as Alice Paul, who is portrayed as the polar opposite of longtime establishment suffragist Carrie Chapman Catt (played by Jenn Colella), who is more willing to play nice and cooperate with smarmy President Woodrow Wilson (a scene-stealing Grace McLean) to win the right to vote. “My provocation is, you need the Alice and the Carrie, you need the young at the gates burning shit down and you need the older folks kind of doing diplomacy behind the scenes,” Taub says. “You actually need both to get things done. And I think that the progressive movement could realize that a little more.”

But although Taub is perhaps more moderate than her character, she is just as sanguine about the future of activism, and just as earnest. In addition to the well-stocked bowl of Jolly Ranchers she keeps in her dressing room, as well as a baseball cap from the off-Broadway theater company Ars Nova (where, earlier in her career, she served as composer in residence) on her wall, she has a Talmudic epigraph hanging up that says: “You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to abandon it.”

“That’s sort of the thesis of the show,” she says. “We’re not gonna get this capital-F fight done [immediately] for equality and justice for democracy in America. A lot of the phrases used by activists are ‘never again, ‘not one more,’ ‘this ends today.’ I feel like there’s sort of a tone of finality of like, ‘We’re going to end this and finish this. We have to believe that’s possible, while also accepting that it’s not, and not letting it diminish our desire and motivation to take action anyway.”

Taub has good reason to look on the sunny side. Suffs, which opened on Broadway in April, is a hit, garnering glowing reviews, six Tony award nominations (including for best book of a musical and best original score), and the backing of mainstream feminist figureheads like Hillary Clinton and Malala Yousafzai, who are credited as producers. “She’s like this warm, wonderful grandma,” Taub says of Clinton. “[She’s] been unfairly maligned, in a lot of ways. She’s someone who kind of sees the humor in everything.”

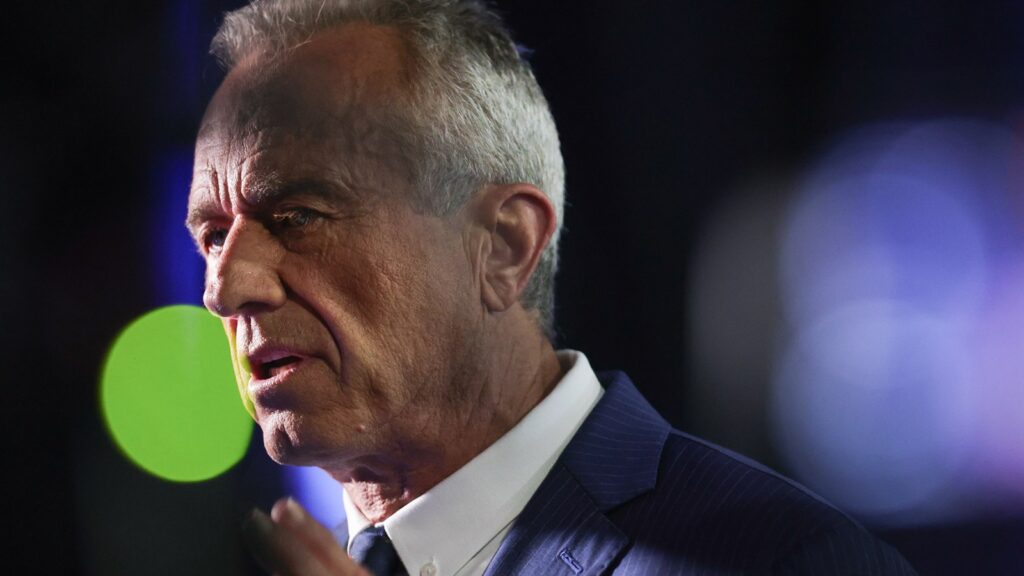

Nikki M. James was nominated for a Tony award for her performance as Ida B. Wells.

Joan Marcus*

The original Broadway cast album, which comes out on June 6, features such musical theater powerhouses as Jenn Colella (who plays Paul’s political rival Carrie Chapman Catt), Nikki M. James (who is nominated for a Tony for her performance as journalist Ida B. Wells), and Emily Skinner (in a small but meaty dual role as wealthy benefactor Alva Belmont, and as the mother of a legislator who — spoiler — casts the deciding vote in favor of women’s suffrage). And the score is stacked with memorable numbers that are sure to be in mezzo-soprano audition songbooks for generations to come, including the contemplative “Worth It,” the barn-burner “Wait My Turn,” and the rousing “Show Them Who You Are.”

Taub first made a name for herself on the downtown theater scene with regular gigs at Joe’s Pub, eventually writing and starring in three critically lauded musical Shakespeare adaptations for the Public Theater. In person, the Taub comes off like an earnest and enthusiastic theater kid in awe of her good fortune, which is kind of exactly what she is. (Though we did not know each other well, we attended the same theater camp in the early 2000s, and I have a very clear memory of her blowing a 350-seat theater away with her rendition of “Gimme Gimme” from Thoroughly Modern Millie.) She grew up in a small town in rural Vermont, obsessively listening to the Ragtime and Full Monty original cast albums (the latter of which featured her now-costar Skinner). “I wore that record out,” she says. “It’s still so surreal.”

Much like the suffragist movement itself, Suffs has had a long and arduous road to its current home at the Music Box Theatre on Broadway. Though the idea for the musical initially took shape in 2014, it underwent multiple workshops and revisions, with Taub struggling to figure out which details of the story to include and which storylines to flesh out. The character of Alice, who left relatively little in her archives before she died in 1977 at the age of 92, was particularly difficult to write.

“It feels to me that it was intentional on her part, to sort of bury the trail to her personal life,” says Taub. “Almost as like a directive to any future historian to say, ‘It’s not about me, it’s about the movement.’” Though Taub says she had initially planned to play a smaller supporting role, she decided to take on the role of Alice after she started incorporating more of herself and her own personality into it. Though she was initially reluctant to give Alice much by way of a personal life, she wrote the song “Worth It,” in which she wrestles with the question of whether to get married and have children or pursue her career in activism, when her mentor, the composer Jeanine Tesori, encouraged her to “get in her head.”

It’s a topic, Taub admits, that hits close to home. “I’m 35. It’s getting to that age of, am I going to have kids or not?,” she says. “I think I would like to, but even now, in 2024, when I enjoy so much more independence and rights and freedoms than Paul did, I still wonder if I could balance them, and if I could be a full artist and a fully ambitious person. [With Alice, her inner life] was the hardest thing to imagine. So I was like, ‘Alright, why don’t I really go there and have her question those things in a way that I’m questioning my own life?’”

In 2020, Suffs was finally set to debut off Broadway. Then the pandemic hit, and the opening of the show was delayed. The show underwent further revisions following the George Floyd protests that year, particularly regarding the characters of Ida B. Wells and Mary Church Terrell, two Black suffragists who are depicted as having been excluded from the mainstream white movement.

Though some critiques of the show have continued to object to its largely white perspective and the sidelining of the Black female characters, Suffs now includes more numbers featuring James and takes care to point out the blind spots and inherent racism of many of the show’s protagonists, such as the white suffragists themselves. Taub says she incorporated scholarship from Black adademics and historians such as Rosalyn Terborg-Penn and Martha S. Jones to further develop the characters, as well as input from the actors themselves.

“A big goal of mine [in the revision process was] to deepen the relationship between Mary and Ida, because they, to me, represent two different tactical approaches to activism,” she says. “I wanted to do what I can to make the musical a gateway to learn more about these women — sort of like accepting that if I try and cram too much in, it’s not going to do service to any of the characters. So how can I open a doorway to be like, here is the first inch in a mile-deep, rich well, where there is history and story and lessons to be learned.”

Still, as a white woman writer, Taub acknowledges there are limitations to how she tells their stories, and didn’t feel she was the right person to tell the story from Wells’ perspective. “If someone writes an Ida B. Wells musical, I will be the first in line to see it,” Taub says. “Someone should absolutely write it. I feel strongly that person is not me. I know that’s not my place.”

Anastacia McCleskey, Laila Erica Drew, and Nikki M. James as Mary Church Terrell, Phyllis Terrell, and Ida B. Wells.

Joan Marcus*

When the show finally opened at the Public Theater in 2022, critics drew comparisons between Suffs and another historically based, relentlessly optimistic musical starring its songwriter and composer: Hamilton. To an extent, this makes sense. Taub counts Hamilton composer Lin-Manuel Miranda as a friend, and he helped provide feedback to Taub while Suffs was in development. “He’s obsessed with craft,” she says. “It was like two mechanics under the hood.” Hamilton and Suffs also both feature two political rivals with shared goals for the movement, if not different strategies for how to achieve them; a comically arrogant white male antagonist; and some similarly anthemic numbers, such as “The March (We Demand Equality),” a spiritual and sonic successor to “My Shot.”

But Taub believes the two pieces are reflective of two fundamentally different political moments. “Hamilton was coming out in the waning days of the Obama years, when people were feeling more hopeful and more empowered about democracy,” she says. “In the earliest days of [Suffs], like 2014-2016, I thought President Hillary Clinton would come see it. But obviously, that’s not where we are. I don’t just mean the looming specter of another Trump presidency — people are disillusioned about voting in general. And I think that’s really interesting to look at [these two shows] a decade apart in the American conversation.”

Since its debut at the Public (it opened on Broadway in April), Suffs has been further reworked. It now features a new opening number, the chirpy earworm “Let Mother Vote” sung by Catt, which uses tropes of benevolent sexism as a means of persuading men to give women the vote. Initially, the opening number was a riff on the early Twentieth-century vaudeville tradition of misogynistic anti-suffrage anthems; but Taub felt that relied too much on audiences’ previous understanding of the suffrage movement, which was essentially nil. “Presenting the status quo of the world that our protagonist is going to come in and disrupt, felt like a much stronger choice for an adaptation of history that people aren’t aware of,” she says. “There was no script to flip.”

A song called “I Wasn’t There,” about how the suffragists were not actually present in the room when the right to vote was signed into law, was cut. “Another challenge of the show has always been, ‘How do I ride the line dramatically between celebration and failure, victory and defeat,’” she says. “You’re not going to ever have full celebration in your lifetime, it’s always going to be some combo. While that song always felt so meaningful in the cast, it was like, we have to have some celebration.” The finale was also reworked to now feature a “driving, forward-feeling” anthem, “Keep Marching.”

Given how many stops and starts took place on the way for Suffs to come to Broadway, there’s one main question that comes to mind: does Taub wish it had come out earlier, at a time when audiences were not inundated with footage of bombings in Gaza and headlines about insurrections or creeping fascism or infringements on women’s reproductive rights? Taub pauses for a second before she answers.

“You can never choose these things,” she says. “But also it feels cosmically right that we’re in an election year, and we’re doing this show in this building, and putting out a cast album for people who can’t necessarily afford Broadway tickets. My hope is we can provide some form of not simplistic uplift, but clear-eyed uplift, that’s like, ‘It’s hard out there. This election is really scary. There’s a lot of forces working against democracy. There’s a lot of reasons to be pissed and be cynical. But we’ve done hardship before, because look at what these women did 100 years ago.”