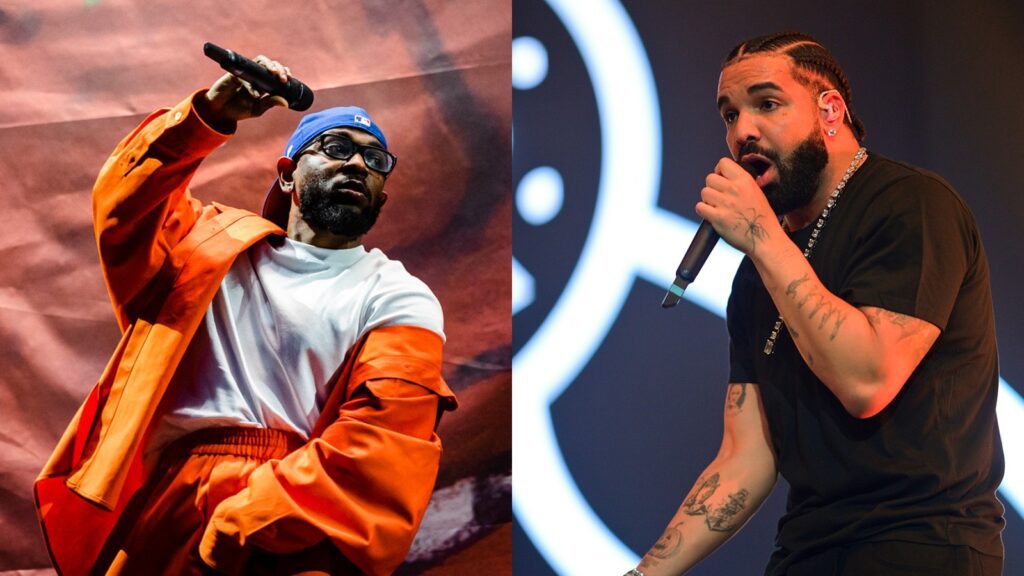

Kendrick Did Everything He Needed to on ‘Euphoria’

I’ve spent the past month theorizing that the root of Kendrick Lamar and Drake’s dysfunction is how philosophically different they seem to be. Their actions speak loudly for two sects of hip-hop in antithetical opposition. While Drake’s three weeks of post-“Push Ups” digital mischief entertained his fanbase and, for some, upped the pressure on Kendrick, the West Coast rhymer’s fans put on an unbothered front, surmising that Drake was anxiously awaiting a potent clapback. True enough, Kendrick opened his diss track “Euphoria” by echoing his fans’ sentiment that “Them superpowers gettin’ neutralized, I can only watch in silence, the famous actor we once knew is lookin’ paranoid, and now spirallin’.”

Some diss songs make listeners perceive an artist differently, but other disses say things people are already thinking in ways that they can’t convey. The Cardo and Kyuro-produced “Euphoria” is the latter. Kendrick doesn’t say many new things, but the way he lobs his insults makes it a haymaker. He laid out a comprehensive laundry list of reasons that he “hates” Drake, apparently revealed that he rejected a Drake collab, and echoed popular sentiments that Drake has ghostwriters, “doesn’t like women,” and is a cultural appropriator with identity issues. Oh, and he lets J Cole off easy with a YMW Melly reference.

The song starts with reverse audio of Richard Pryor noting, “Everything they say about me is true!” while playing The Wiz in the 1978 film, planting his flag for the diss’ overall premise in the same way that Drake’s “Drop and give me 50” refrain did on “Push Ups.” It’s an election year, so it makes sense for both men to emphatically stump their platform: Kendrick says Drake is a phony, and Drake says Kendrick was in an unfavorable deal that forces him to compromise his artistry. Maybe both things are true, and fans have to decide between other factors to pick their winner.

Kendrick came out of the gate as if he had indeed been waiting to shit on Drake for four years (or more), passionately darting through different flows and inflections throughout the track. The colorful voices hampered the impact of his lines at times, but he didn’t go overboard. Kendrick has never done a full-on diss song, but he sounded like a seasoned vet at the sport, mixing in slick double-meaning with ominous warnings and good old-fashioned slapstick moments. Humorously, he goes on multiple extended runs where he simply lists what he hates about Drake, rhyming, “I even hate when you say the word ‘Nigga,’ but that’s just me, I guess.” But then he also gets into wordplay, rhyming, “My first one like my last one, it’s a classic, you don’t have one. Let your core audience stomach that, didn’t tell ’em where you get your abs from.” When he tells Drake, “Tell BEAM that he better stay right with you,” he references frequent Drake co-writer BEAM and “beam” as slang for a gun.

He calls Drake a “master manipulator” multiple times on the track, and states “Don’t tell no lie ’bout me, and I won’t tell truths ’bout you,” hinting at more in his arsenal in the same way Drake did on “Push Ups.” While “Push Ups” listeners worried that Drake went below the belt by saying the name of Kendrick’s wife on the song (and recently wearing a shirt from her community college on Instagram), Kendrick didn’t take the bait and go nuclear, even rhyming, “We ain’t gotta get personal, this a friendly fade, you should keep it that way,” later in the song.

That said, Kendrick takes plenty of personal shots. He claps back at Drake’s “Push Ups” assertion that he’s in a bad deal, also noting that Drake “was signed to a nigga that’s signed to a nigga that said he was signed to that nigga.” He rhymes, “I know some shit about niggas that make Gunna Wunna look like a saint,” referencing the controversial “snitch” label put on Gunna. Kendrick also suggests that Drake tried to file a cease-and-desist on his, Future, and Metro Boomin’s “Like That,” and that the Toronto rhymer wanted to bury the hatchet at one point with a “feature request,” but he wasn’t with it because “You know that we got some shit to address.” Curiously, he also suggests Drake is an absentee father later in the track. Some of the lines on “Euphoria” feel like Kendrick is treading the out-of-bounds line like an NBA player coming down with a rebound; time will tell what Drake decides after his official review.

Kendrick’s biggest gripe is that Drake isn’t who he depicts himself as. “Once a lame, always a lame. Oh, you thought the money, the power, or fame would make you go away?” he rhymes. And while rhymes like “Have you ever walked your enemy down like with a poker face?” seem like a set of general lines, they shoot at Drake’s AI Pac assertion that “All that shit ’bout burning tattoos, he is not amused, that’s jail talk for real thugs, you gotta be you.” He decides to “be him” by rapping about his traumatic life experience, magnifying that Drake likely has no similar stories to match. That tactic makes the second half of the track, where he pokes deeper at Drake’s identity, hit harder.

Later in the song he rhymes, “How many more Black features till you finally feel that you Black enough?/I like Drake with the melodies, I don’t like Drake when he act tough.” He also snipes at Drake’s now-disturbing misogyny, humorously rapping, “When I see you stand by Sexyy Red, I believe you see two bad bitches, I believe you don’t like women, that’s real competition, you might pop ass with ’em.” And Kendrick claims to be saying all this on behalf of the culture.

In some ways, he is because most of his talking points feel straight off the X timeline. Many things are true: Hip-hop is a Black art form, Black people shape popular culture, and we can be too inviting with that power — for some reason, we still talk about “cookouts.” In 2006, upon Drake’s first arrival, the notion of a biracial child actor who’s on tape using the hard “-er” becoming a rap star seemed far-fetched. But he had the cosign of Lil Wayne, then the hottest rapper in the world, and he was undoubtedly talented. And then he made “Headlines,” “Marvin’s Room,” and “Hotline Bling,” and crafted a catalog that overshadowed any qualms many had about his identity, origin story, or even penmanship. The Canadian was a product of Americans’ self-preserving knack for dissonance.

He grew into the role he sought, and the Degrassi kid had become the biggest rap star in the world. By the mid-2010s he could’ve simply toasted to his biopic-worthy victory — but he seemingly got drunk off the power. The Common and Meek Mill and Pusha T beefs beget one too many bars about shooters. “Diss me and you’ll never hear a reply for it” seemingly turned into seething bitterness demonstrated in random shots at Megan Thee Stallion and Rihanna. Somewhere along the way, the Drake experience had changed in a polarizing manner. He acknowledges it himself on “The Shoe Fits,” where he raps, “To all the ladies wonderin’ why Drake can’t rap like that same old guy: It’s ’cause I don’t know how anymore.” So many of his recent actions are making people rethink our collective decision to embrace him in the first place way back when.

Drake’s achieved a diverse appeal in a way that perhaps no other rapper ever has. But his means of doing so left a lot of ammo on the ground for his detractors to use. Kendrick took advantage of it on “Euphoria,” an eruption of disdain that said what many feel Drake needs to hear in a way few people could.