Amid Debates Over Black History, a Park Stands For Truth and Reconciliation

M

y recent trip to Montgomery, Alabama, wasn’t my first visit. I had previously explored the city and the sites associated with Bryan Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) in 2019, in what turned out to be a pivotal moment — after Donald Trump’s ascent to power, but before the Covid-19 pandemic brought the world to a standstill. It was also before the 2020 killing of George Floyd sparked widespread protests and a year of reconstruction.

I remember the world around me, even Trump’s presidency, making sense as I left the Legacy Museum, dedicated to the legacy of slavery in the United States. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which honors victims of lynching, inspired the thought that maybe — just maybe — the worst was behind us. It feels like a lifetime ago.

I struggled with the idea of returning this spring to experience a new EJI site, to witness the unveiling of the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park. Like many Americans, I imagine, I am too anxious about the future of the country to look back at history, again. I anticipated being triggered by the Legacy Museum and having my grief compounded by the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. But the new sculpture park promised a revival of sorts.

“We want everybody to come here — and don’t be afraid — nothing bad is going to happen to you if you come,” Stevenson says about the new, complete sites. “Now you’re going to have to understand some things — you’re going to hear some things that are challenging, and uncomfortable. But that’s part of how we grow.”

So, despite my reservations, or maybe because of them, I returned to Montgomery to be saved from my anxieties and to receive, Lord willing, some fresh measure of hopefulness. You can get to the park by boat via the muddy waters of the Alabama River, which once trafficked enslaved Africans. Another route is via a shuttle that crosses railroad tracks laid by the enslaved, and which also served as delivery networks for human cargo. Together, these networks transported hundreds of enslaved Africans to Montgomery each day, according to estimates from the Equal Justice Initiative. By 1860, 66 percent of Montgomery’s population was enslaved, 23,710 people, a larger enslaved population than Mobile, Alabama; New Orleans; and Natchez, Mississippi.

The rushing river, the sound of a distant train approaching, and the towering trees in every direction are the park’s first exhibits. They were passive participants in the history. They were witnesses.

A series of circular paths cuts through the 17 acres that make up the park. As I wandered them, I encountered a symphony of voices rendered in wood, stone, and metal. One bend features 170-year-old dwellings acquired from former cotton plantations nearby, a whipping post, and replicas of a rail car and a holding pen. Others are dotted with sculptures designed to tell a story — works by Alison Saar, Kwame Akoto-Bamfo, Hank Willis Thomas, Cliff Fragua, Wangechi Mutu, Rose B. Simpson, Theaster Gates, and Kehinde Wiley.

Simone Leigh’s “Brick House” greets visitors to the park.

EQUAL JUSTICE INITIATIVE/HUMAN PICTURES

At the entrance of the park, visitors are greeted by a 16-foot-tall bronze bust of a Black woman with a body shape inspired by the dwellings of the Musgum people of Cameroon and Chad. Artist Simone Leigh’s “Brick House” is stoic and ancestral, “mighty, mighty,” like the Commodores song.

Amid contentious debates over book bans, assaults on Black scholarship, and the manipulation of educational curricula across the United States, the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park emerges as a beacon of truth and reconciliation.

Consider, for example, that just in March, Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey signed a bill banning state funding for diversity, equity, and inclusion programs in schools, public colleges, and state agencies. The new law also imposes restrictions on what it calls eight “divisive concepts,” including — poignantly — the idea that “any individual should accept, acknowledge, affirm, or assent to a sense of guilt, complicity, or a need to apologize on the basis of his or her race, color, religion, sex, ethnicity, or national origin.” According to The Chronicle of Higher Education, 82 such anti-DEI bills have been introduced in 28 states and Congress since 2023, with measures signed into law in 10 states.

“We cannot be intimidated or silenced by some foolish legislation or reckless politicians who are trying to characterize [learning about history] as destructive, when in fact, it’s the silence that’s been so destructive,” Stevenson says. “Of course, there are going to be people who try to politicize and demonize — all of that stuff. That’s how you know you’re doing something powerful, because people are afraid of what could happen when their children and their grandchildren begin to understand that there’s a better way to move through this world.”

EJI’s sites are outgrowths of its work providing free legal representation for people on death row. (Stevenson chronicled one of his early cases in the bestselling 2014 memoir Just Mercy, which became a feature film in 2019, starring Michael B. Jordan.) EJI is financially independent, with some of its earliest seed money coming from Stevenson’s own MacArthur “genius” grant in 1995. The nonprofit has attracted generous support in the years since from people who believe in Stevenson’s mission.

Bryan Stevenson, who founded the nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative, just opened the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park in Montgomery, Alabama, this spring.

Wulf Bradley/The New York Times/Redux

“I have not taken a penny of state or federal money for any of our sites. The truth is, we haven’t been offered any state or federal money,” he says with a chuckle. “At this point, I wouldn’t take it if it was offered, because we have to have the autonomy and the latitude to tell the truth without fear that our ability to operate or to function is going to be compromised or undermined. That has allowed us to do what we think is right and do what we think is important, despite the winds out there that are pushing in an unhealthy direction.”

Howard Robinson, a Montgomery-based historian, member of Alabama’s Black Heritage Council, and associate library director at Alabama State University, recalls the Equal Justice Initiative’s beginnings were humble amid a similar landscape. EJI was still merely a legal nonprofit housed in an unassuming building on Commerce Street more than a decade ago. When Stevenson learned of the source of said commerce — slave markets made up of structures that peppered downtown Montgomery — he set out to put up historical markers at those sites, including one in front of his own organization’s building, the site of a former warehouse for the enslaved.

When the request to erect the markers in 2013 first went up before the Alabama Historical Association, the group declined to sponsor them because of the “potential for controversy,” according to The New York Times. Then-Mayor Todd Strange expressed concerns that one of the markers, which named slave traders, would offend the descendants of former slavers, before ultimately backing the project.

“It gives you a sense of the climate of Montgomery, that there was hostility and reluctance to address a marker that draws attention to elements of the city’s past,” Robinson says.

Today, Stevenson has achieved so much more in the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park. He has assembled what the Bible describes as “a great cloud of witnesses” that empowers believers to “throw off everything that hinders and the sin that so easily entangles.”

“I really do think we have to have that attitude that our foreparents had, which is ‘Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around,’ ” he says. “We just have to be really persistent and diligent, and determined. I am persuaded that truth is powerful, that you can’t ultimately succeed in suppressing truth with fear or anger.”

Through her work in the organization’s educational programs, EJI project manager Mia Taylor has seen firsthand the transformative power of engaging with history. She keeps a log of poignant reflections from students who’ve visited the sites, expressing how learning about their history — including the most painful parts — has empowered them, not traumatized them, as some lawmakers have suggested would happen.

“If we don’t talk about it, we wouldn’t be honoring those who made the sacrifices to get us where we are” is how one student put it after their visit.

“You try to explain history, but without the full context, it’s really hard to fully understand,” Taylor says. “Glossing over certain parts does everyone a disservice.”

Rose B. Simpson’s “Counterculture” series is not too far away from “Brick House.” Its dyed and cast concrete figures stand approximately 10 feet tall, with hollowed eyes honoring the Indigenous peoples as the first stewards of the land.

“They’re about accountability,” Simpson reflects, “and how you act when you know that you’re being seen by what we consider inanimate.”

The inclusion of Simpson’s work, and that of other Indigenous artists, shows the park’s ethos — a commitment to telling the full, complex story of America, inclusive of all its voices and perspectives.

Farther into the park, Alison Saar’s “Tree Souls” and Hank Willis Thomas’ “Strike” offer profound reflections on resistance and solidarity. Saar’s sculpture depicts figures suspended by gnarled roots, while Thomas’ stainless-steel masterpiece captures the tension of a confrontation between a protester and a police officer — a haunting reminder of struggles past and present.

“Strike” reflects the complex interplay of struggle and peace that has characterized Black American history.

Hank Willis Thomas’ “Strike” is one of the sculptures at the park.

EQUAL JUSTICE INITIATIVE/HUMAN PICTURES

“I was thinking a lot about the ways in which that kind of [resistance] has taken various forms,” Thomas explains. And the choice of shiny, reflective stainless steel is also significant. “It’s important for us to see ourselves in moments in history,” he says.

Saar, a Los Angeles-based sculptor and artist, says her contribution is meant to explore the sanctuary found in swamps and other hostile environments by escaped enslaved Africans, so-called maroons.

“These spaces were not ideal,” Saar says, “but they were a refuge for a lot of people that were trying to somehow survive outside of the horrors of colonialism.”

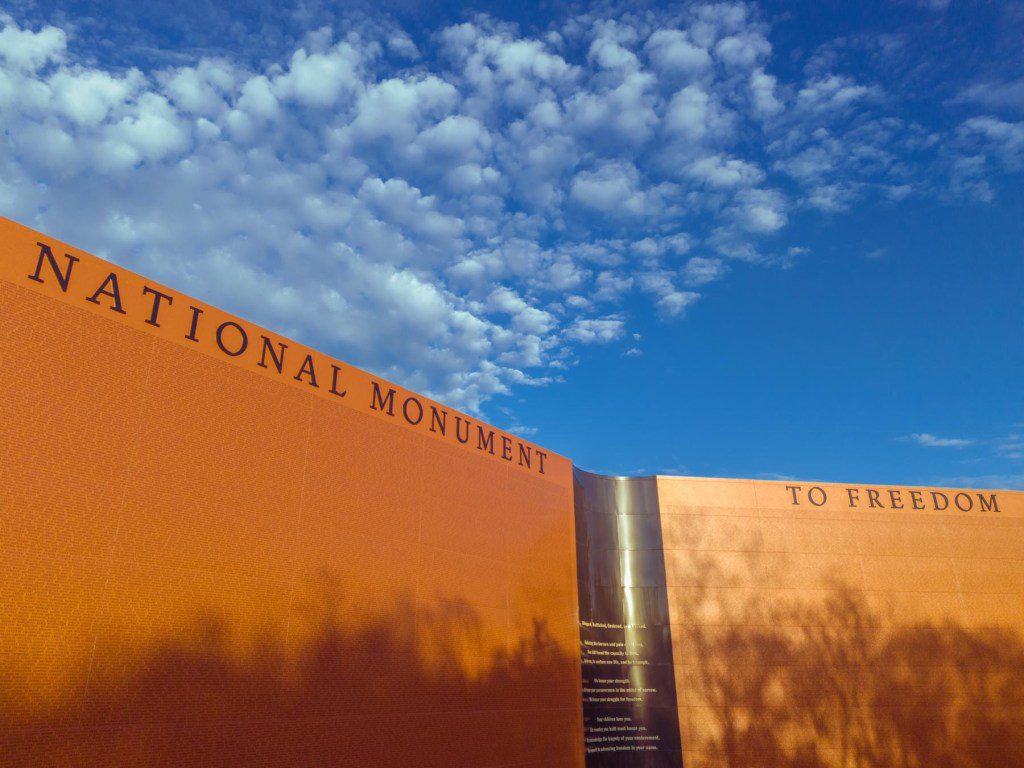

The journey culminates at the National Monument to Freedom, a great metal wall standing 43 feet tall and stretching 155 feet long. Drawing from the 1870 Census, the monument evokes more witnesses, listing, according to EJI, “over 122,000 surnames that nearly 5 million Black people adopted in 1870 and that tens of millions of people now carry across generations.”

More than 500,000 people a year visit EJI’s sites, with the new monument likely to attract even more. For them, one unavoidable takeaway is that white supremacy is a myth along with American exceptionalism. Another is that Black people are here to stay. America has already done its worst, and we’ve survived it all. We’ve persisted, and come out on the other side, as Maya Angelou put it, having encountered many defeats, but undefeated.

There’s the railroad and river, both delivery networks for human cargo. Court Square is also nearby, at one time one of the largest slave markets in the South, and the Alabama State Capitol building, which served as the Confederate Capitol when Montgomery was named the first political capital of the Confederacy in 1861.

The final sculpture is the soaring National Monument to Freedom, which lists “over 122,000 surnames that nearly 5 million Black people adopted in 1870.”

EQUAL JUSTICE INITIATIVE/HUMAN PICTURES

Civil Rights Movement history is another current running through the city. Both Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. emerged as movement leaders from the Montgomery bus boycott, which began in 1955 and culminated in 1956 in the desegregation of public transportation throughout the country.

In 1961, future congressman John Lewis and other Freedom Riders survived a brutal attack by a white mob at the Montgomery Greyhound bus station. Four years later, in 1965, activists marching from Selma to Montgomery to demand voting rights persisted despite terrorist violence, their bloody example inspiring the introduction of the Voting Rights Act to Congress by Lyndon Johnson.

The Freedom Monument Sculpture Park succeeds in bringing this epic history to life. How could I not feel something on such hallowed ground, staring up at the soaring National Monument to Freedom, scanning the vast list of surnames and finding my own, “Ramsey,” carved into steel in a row at the bottom right of the monument?

According to the 1870 Census, the first year in which formerly enslaved Black people were officially counted as people and citizens, Ramseys were piecing together free lives all over the country. Data made available by EJI to all visitors further shows a large number, 309, in Georgia, 75 of whom were living in Columbia County. I know from family research that these are my Ramseys.

The author found his own family’s name — Ramsey— carved in the National Monument to Freedom.

COURTESY OF DONOVAN X. RAMSEY

I have been working to identify the right slaver for decades, in part by eavesdropping on genealogy message boards. On occasion, the white Ramseys reference slaves and plantations explicitly while discussing wills and other property records, allowing me to confirm names, dates, and locations connected to my ancestors. (I’d announce my presence and make targeted appeals if I weren’t afraid of being blocked.)

These Black people — part Nigerian, part Cameroonian, part English and Irish — likely took their name from a white man who owned them. It’s likely all they took with them when finally freed. Despite their bleak entry into American life, I imagine some also had the irreverence, optimism, good taste, good teeth, hairpin triggers, and heart of the Ramseys I have been blessed to know in this life. I doubt I’d be here if they didn’t.

Do I feel hopeful? Not yet, but certainly encouragement from a “great cloud of witnesses” to “throw off everything that hinders and the sin that so easily entangles, and let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us.”

As the sun sets over the park, casting long shadows across its sculptures, one cannot help but feel a sense of reverence and awe at its grand existence. In the face of legislative assaults on diversity and equity, the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park is one space where the voices of the past echo through the present, where wounds of history are disinfected by the light of truth.